Southeast Asia is experiencing a thrilling wave of species discovery

The so-called "Klingon Newt," newly discovered in northern Thailand

The newt’s toes and tail are creamsicle orange, a striking contrast to its ochre-brown torso. Its head is shaped like a hexagon.

But its defining feature is a craggy ridge of bones along its back and skull. All together, the creature looks remarkably like a Klingon.

Or rather, a Klingon’s forehead that somehow sprouted tiny limbs.

The jungles of Southeast Asia are teeming with undiscovered species. Until recently, this creature — full name, tylototriton anguliceps — was one of them.

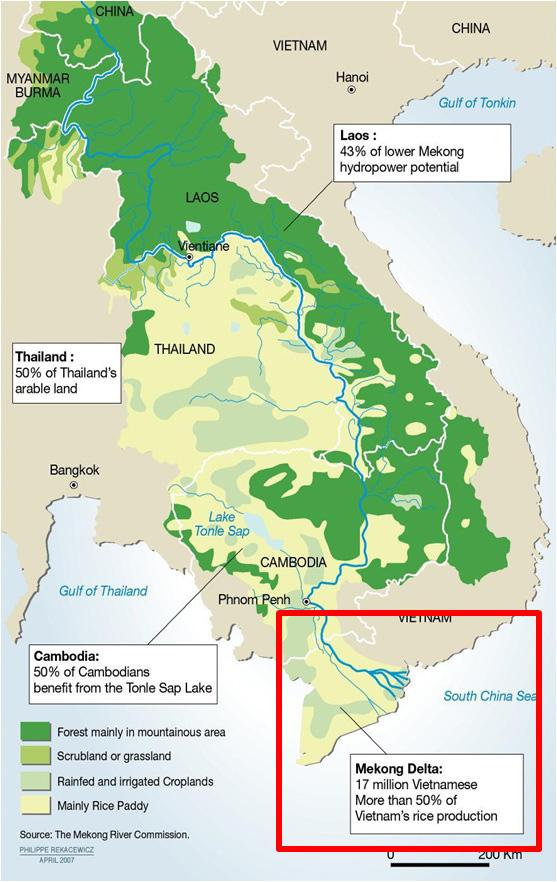

Now it’s among a wave of species discovered in and around the Mekong River.

In the minds of many Americans, the river recalls death; its delta region saw gruesome battles following the US invasion of Vietnam. But the river is, in fact, a great giver of life — much of it slithering.

Scientists trudging through the Greater Mekong region are finding a surprising number of previously uncatalogued species. “There are still a lot of unexplored areas,” says Jimmy Borah, a Southeast Asia-based program manager with the World Wildlife Fund.

“But if you look deeply, you’d be surprised by how many species you can find,” Borah says. “We’re finding more than two per week.”

This is not just an Asian phenomenon. Centuries after we began cataloging plants and animals in earnest, humans are still finding loads of new ones. In fact, in a good year, we can rack up as many as 20,000 newly discovered species.

This pace is owed in large part to technology: online archiving, precision DNA tests and cheap flights to remote lands. The world’s scientists know that places such as Madagascar, for example, are rife with undocumented creatures. But they no longer have to reach its shores via creaky sailboats.

Actually spotting new creatures means sticking your nose in rotting logs or checking under rocks — both choice hangouts for the Klingon lizard. It dwells near the Thai-Myanmar border in a province called Chiang Rai.

“There’s a lot of energy involved in finding new species,” Borah says. “Not many people would immediately notice [the Klingon newt] if they came across it in the forest. Most people would think, ‘Oh, it’s just a lizard.’ But there are people looking for new species that can spot all kinds of morphological differences.”

Scientists who hunt new species are enjoying what some environmentalists call a “golden age of discovery.” When it comes to wildlife preservation — often a horribly depressing subject — this is a rare bit of upbeat news.

But don’t get too comfortable.

As the term “sixth extinction” suggests, there were five others in the past. Those catastrophes were caused by ice ages and asteroids. But this one is brought on by human activity. Its causes are varied but involve climate change, deforestation, poaching and industrial farming.

Thanks to humans, much of the planet’s sentient life is now narrowed down to a band of lifeforms that we like to eat. In fact, if you exclude small critters, most hot-blooded creatures standing on the Earth’s surface live their entire lives in captivity.

The sort of creatures usually evoked by the word “wild animal” — say, a tiger or a fox — are increasingly hard to find. They’re severely outnumbered by domesticated animals such as dogs and chickens.

According to the macro-historian Yuval Noah Harari, livestock accounts for roughly 60 percent of the Earth’s biomass, at least when it comes to animals larger than a few pounds. Humans clock in around 30 percent. Wild animals? Maybe 10 percent.

Harari puts it succinctly: “Homo Sapiens has rewritten the rules of the game. This single ape species has managed within 70,000 years to change the global ecosystem in radical and unprecedented ways.”

So what does all this mean for creatures like the little Klingon newt?

Scientists don’t know much about the newt at this point. But they do know it’s highly sensitive to man-made poisons in the form of pesticides. Researchers such as Borah also worry about another human threat: jungle poachers.

“Whenever a new species is discovered,” Borah says, “illegal wildlife traders will think, ‘Oh, there’s a new species here. Maybe we can sell it for our own profit.’”

He cites the example of a snake, recently discovered in Laos, with brilliant irridescent colors shimmering on its head. (Researchers have already dubbed it the “Ziggy Stardust” snake.)

This type of creature would be easy to market within a global illicit wildlife trade — centered in Asia — that rakes in an estimated $10 billion per year.

“Whenever a new species is discovered,” Borah says, “it becomes easy for poachers to throw out some new superstitious idea. They might say, ‘This snake has a rainbow on its head so that’ll give you power.’ It’s pretty easy to convince consumers.”

At this point, there’s no way of knowing how many Klingon newts or Ziggy Stardust snakes are wriggling around Southeast Asia. At this point, neither are fully protected by the core international treaties that attempt to protect wildlife from smugglers.

For biologists, tracking down and identifying new species is easier than ever before. Yet they’re pitted against humanity’s destructive hand in a race to catalogue as many species as possible before they’re eradicated.

Ideally, the Klingon newt will persevere — but if it doesn’t, it wouldn’t be the first creature to get wiped out within a mere decade of its discovery.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!