The team behind "Kosovo if Trump Wins" is pictured here, from left to right: Fitim Krasniqi, Argjend Haxhiu and Kushtrim Krasniqi. All three are devout Muslims. They are also pro-American like most people in Kosovo.

Fitim Krasniqi’s obsession with the US presidential race began during the primaries. The 26-year-old web developer "felt the Bern" from all the way in Kosovo. As a devout Muslim, he says, he saw nothing good in Donald Trump — except for the sheer value of his name and gift for attracting publicity.

But that was enough reason for Krasniqi to take a page from Trump’s playbook.

"I thought to myself, 'It is a great idea to just jump on the bandwagon and just promote our little country here in Kosovo,'" he says.

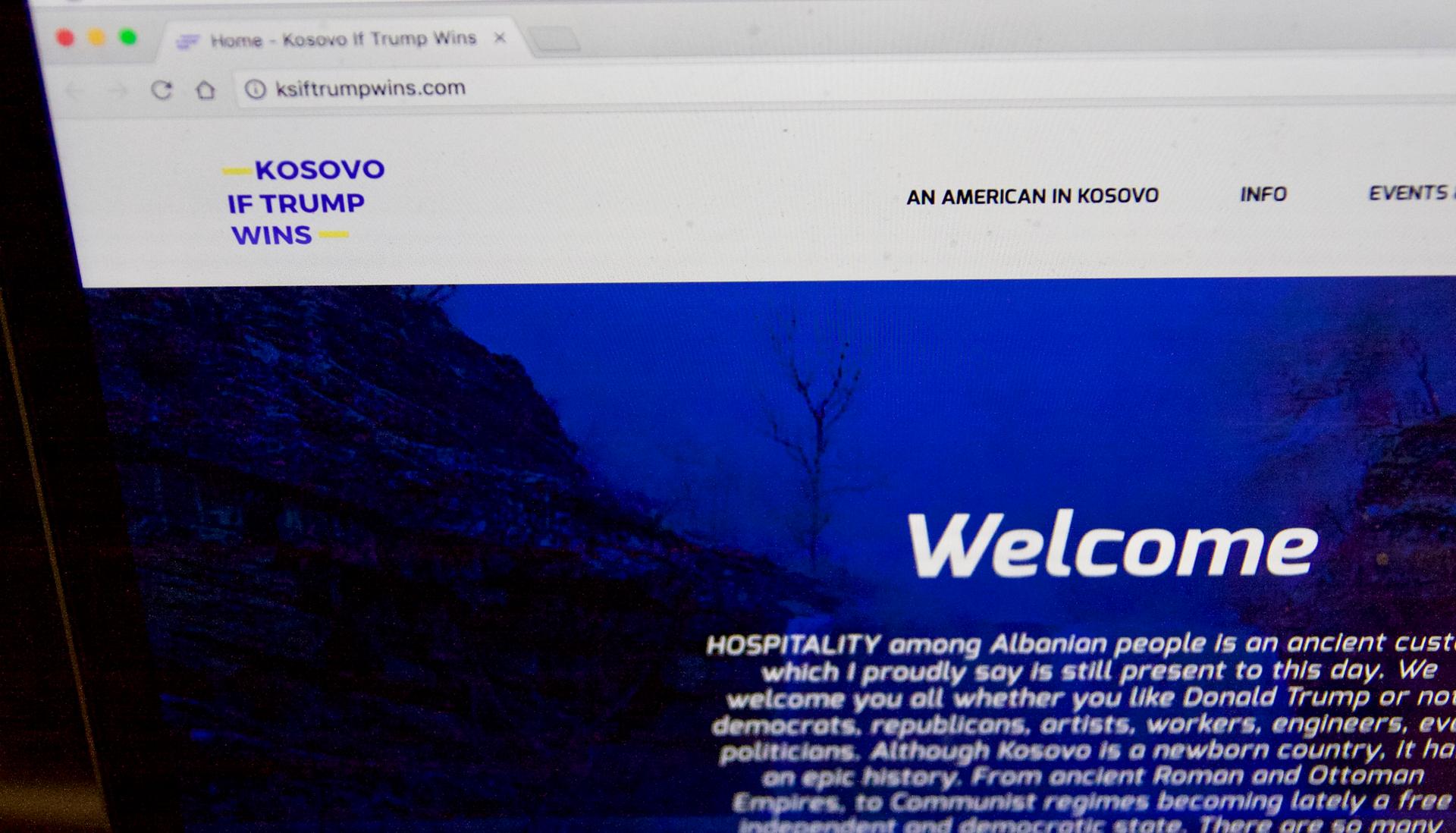

Together with his 30-year-old brother, Kushtrim, and a colleague, 24-year-old Arjgend Haxhiu, he launched a website, “Kosovo if Trump Wins,” in October. It cheekily suggests that Americans should move here in the event of a Trump victory. Apart from a few profiles of Americans who live in Kosovo, the website doesn’t take the suggestion seriously.

It’s really an online travel guide, selling people on coming to visit. The use of the Trump name, which appears in the logo, was a gimmick to attract traffic to the new website. Like many people in the United States and across the world, they were certain that Trump would lose the election. The team had even been discussing what to rename the website after Nov. 8.

On Nov. 9, the day after the election, they faced an unexpected problem: The site crashed because their server couldn’t handle the 10,000 page views in a day.

While they got the traffic they wanted, they’re now facing the sobering reality of what it all might mean for them personally. The website creators are all Muslim, like the majority of Kosovars. And Haxhiu and Fitim Krasniqi’s company, Creotive, makes a large part of its money in IT outsourcing work for American clients, doing coding and web design at a steep discount from what someone would earn in the United States.

“We are like Donald Trump’s nightmare,” Haxhiu says. “It’s kind of a bit scary now to think about the worst-case scenario that’s going to happen.”

It seems unlikely that Trump would give much direct consideration to Kosovo, as a small, relatively poor country that is at peace. But his presidency could have serious implications for Kosovo’s relationship with the United States, its most powerful ally. During the campaign, Trump questioned US commitment to NATO, which has a peacekeeping force in Kosovo. And he has praised Russia's Vladimir Putin, who has consistently challenged Kosovo’s international legitimacy.

For Kosovo’s Albanian majority, it gets to the heart of how the country came into existence.

Fitim and Kushtrim were kids when President Bill Clinton led the NATO bombing campaign in 1999 that ended Serbia’s crackdown in Kosovo. They have fond memories of the arrival of thousands of NATO peacekeepers, including US soldiers, who were stationed in their hometown, Gjilan.

Kosovars’ love for the US has endured across three presidencies. There’s a statue of Bill Clinton (behind a boutique named after Hillary) on a boulevard named after him. It intersects with George Bush street, in honor of George W. Bush, who backed Kosovo’s 2008 independence from Serbia. The American flag is a more common sight here than in many parts of the United States. A pop folk group even recorded a kitschy song, “Thank you USA.”

“The United States for all of us is this father figure, this role model,” Fitim says. “We look to the US to be this overall model of freedom, and everything we want to achieve.”

American support of Kosovo’s independence, millions of dollars in aid and the continued presence of US soldiers, bolsters that relation. There are only around 600 US troops on hand. But they represent the second-largest contribution to the NATO peacekeeping force. The US Army has a base here, too, that can hold 7,000 troops. Kosovo still doesn’t have its own army.

But the United States is not beyond reproach in this small country of 1.8 million people. The US Embassy’s close involvement in domestic politics has drawn sharp criticism at times and accusations that it has propped up corrupt leaders.

Yet even critics generally recognize that the United States has an important role to play and are anxious about the incoming US administration.

At this point, Kosovars don’t have much to go on. The names circulating for secretary of state include Senator Bob Corker and John Bolton, a former US ambassador to the UN. Corker is a familiar friend. Bolton opposed Kosovo’s independence. A 1999 interview Trump gave to Larry King has also sent mixed signals. Kosovar media have touted it as assurance that he backed the 1999 intervention. Serb media have taken the opposite view. Not surprisingly, the interview is vague. But Trump is clear about one thing: He would have done it differently and better.

In Northern Mitrovica, the largest Serb-majority city in Kosovo, Trump’s election was cause for celebration. Billboards went up with a picture of him behind an American flag, with the message: “Serbs Supported Trump.” Serbs, who make up about 5 percent of the population, see hope of a possible change in US policy. Serbs in Kosovo came out on the losing side of the 1999 war and live in a country most of them wished never came into existence. Many see Putin as their protector and more loyal than their own government, which has inched closer to a de-facto recognition of Kosovo through EU-mediated talks.

But for the vast majority of Kosovars, who are Albanian and to varying extents Muslim, Trump could test a 17-year relationship. While it would take a lot for Kosovars to sour on the US, Krasniqi says that Trump shouldn’t take the relationship for granted. It would be a bad idea, he adds, for the new president to try to charge Kosovo for continued US protection.

“We don’t have a lot of money,” Krasniqi says. “We’re not the richest part in the world. Maybe we’d be devastated because we’d feel cheated, to say the least, from our role model, our greatest ally, our greatest friend.”

There are few places in the world with such fervent US support, let alone one with a mostly Muslim population. The only comparison is Albania itself. Most Muslims in Kosovo are not devout like Krasniqi is. But radical Islamism has seeped in, and according to government figures, 300 people have gone to Syria and Iraq to fight for ISIS or al-Nusra.

Krasniqi, for his part, doubts that a strained relationship would translate into a rise in extremism.

Ultimately, he is hoping that Trump’s campaign rhetoric about NATO and Muslims was only talk. His brother, Kushtrim, is convinced that's the case.

“I think he just played us,” he says.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!