Reservoirs are sources of drinking water, hydropower and … tons of greenhouse gases

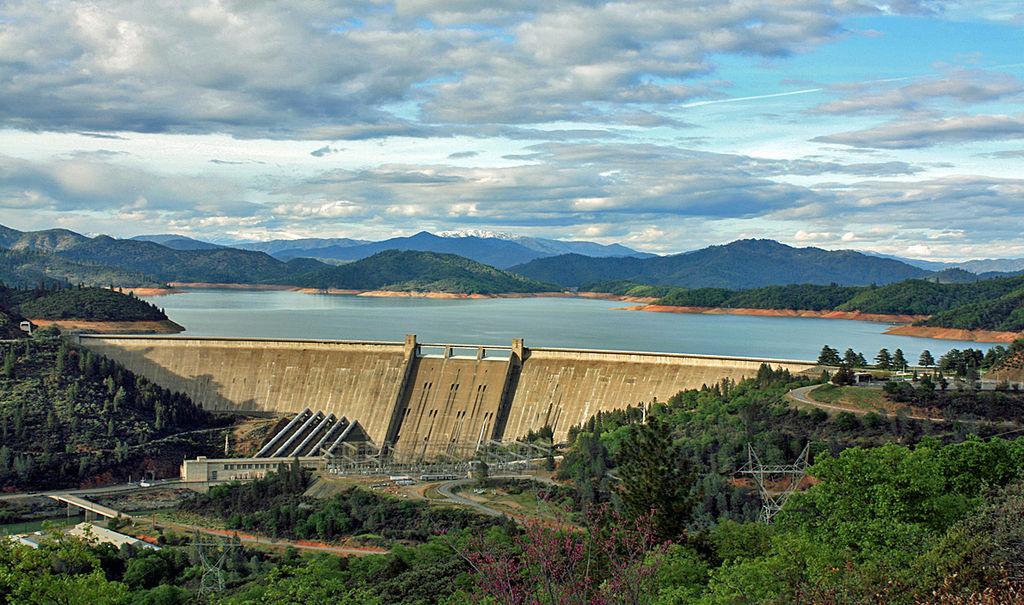

Shasta Dam and Shasta Lake are pictured here in 2009. They're located in California’s northern Sacramento Valley. Shasta Lake is the state's largest reservoir.

Reservoirs provide flood control, irrigation, drinking water and recreation for millions of people worldwide. And when positioned behind hydroelectric dams, reservoirs are also major sources of low-carbon electricity — slashing our reliance on greenhouse gas-emitting fossil fuels.

Sounds squeaky-clean, right?

Not so fast: A new study confirms that reservoirs emit their own greenhouse gases — a lot of them. In fact, when taken together, the world’s reservoirs have as big an impact on the Earth’s climate as the population of Canada, the ninth-largest greenhouse gas-emitting country.

“It turns out the reservoirs are a really good place to rot organic matter,” says John Harrison, an associate professor at Washington State University’s School of the Environment in Vancouver, and one of the study’s authors. “And that makes a lot of methane. And methane is a really potent greenhouse gas. In fact, on a per-molecule basis, it's about 35 times more potent than CO2.”

Organic matter — algae, terrestrial plant material, you name it — can collect in reservoirs in any of a few different ways.

“Organic matter that's there when a reservoir is flooded will rot,” Harrison says. “Organic matter that flows in from upstream or grows in a reservoir … when it rots in the absence of oxygen, can be converted to methane, and then emitted into the atmosphere.”

All told, the greenhouse gas emissions from reservoirs add up — and we don’t need to pick on Canada to prove it.

“[Reservoirs are] also a similar source in magnitude to important human sources like rice cultivation, or the burning of biomass to make electricity,” Harrison says. ”So it's a really important source, and yet it's not counted in the current UN accounting of greenhouse gases.”

Harrison isn’t hoping that the study’s findings will discourage construction of new reservoirs. For one, although reservoirs emit greenhouse gases, he notes they can also help us mitigate the effects of climate change, by acting as buffers against cycles of flooding and drought. But he does think citizens and governments need to be more aware of the trade-offs.

“We're trying to round out the picture of what happens when a river is dammed, so that policymakers and the general public have a better understanding of the consequences of every reservoir that's built,” Harrison says.

That’s not to say that we can’t reduce the levels of greenhouses gases emitted by reservoirs. Harrison sees minimizing the amount of organic material in reservoirs as the best place to start.

“One thing that we’re really excited about is the potential to site reservoirs in ways that reduce greenhouse gas emissions to the atmosphere, and to manage the organic matter inputs to reservoirs that lead to those greenhouse gases eventually,” Harrison says.

This article is based on an interview that aired on PRI's Science Friday.