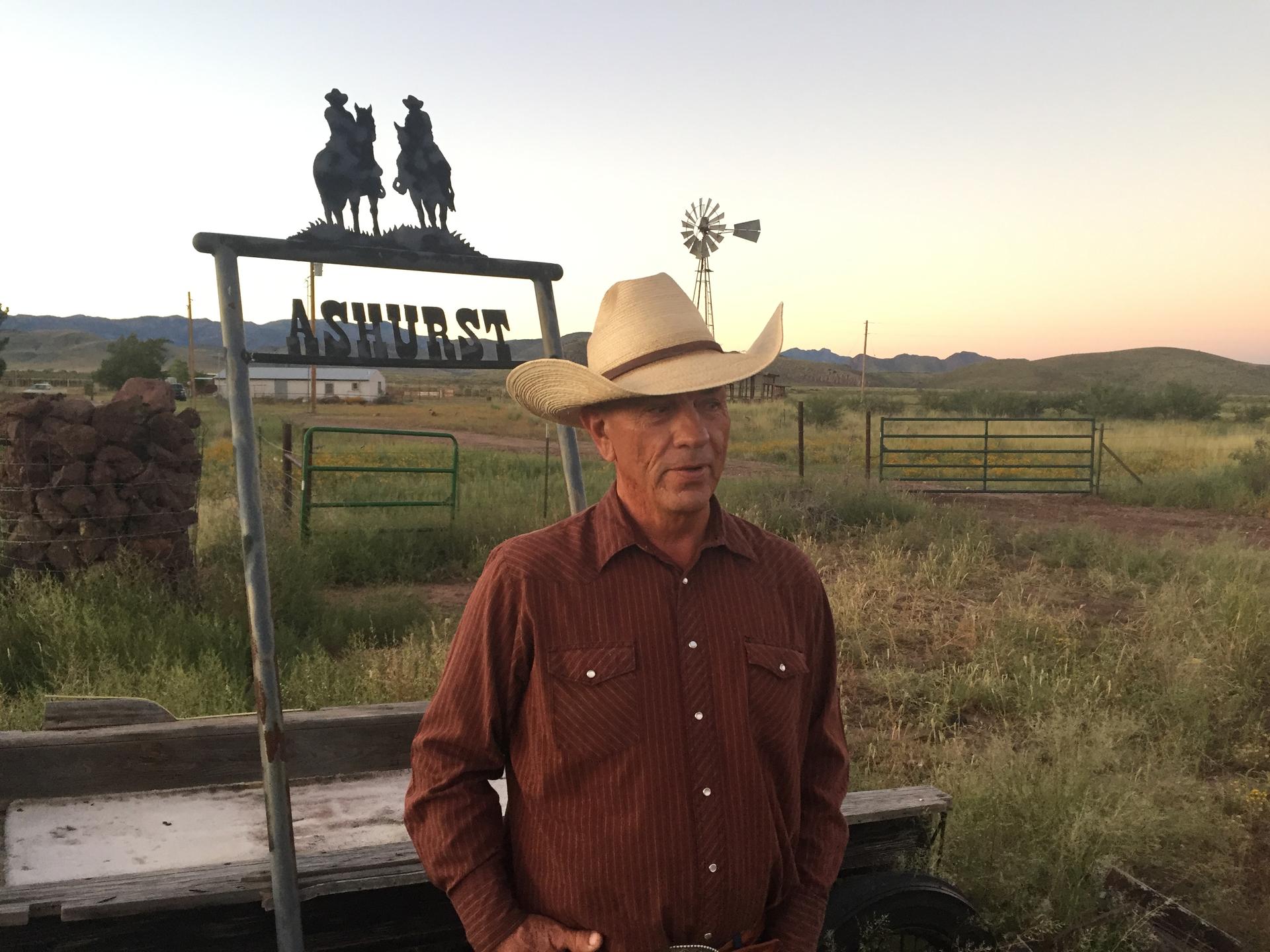

This rancher in Arizona doesn’t necessarily want a wall — but he does want more done along the border

Ed Ashurst lives just north of the US-Mexican border in Arizona. And he says he sees smugglers and faces violence every day. He wants the US Border Patrol to do more.

A border patrol officer was parked on the gravel side-road to the Ashurst ranch, about 20 miles north of the Mexican border in Arizona, when we arrived. He was just watching the rare car go by and looking for anything suspicious.

There’s been a sharp increase in funding for the US Border Patrol since 2005 — the number of agents has doubled in that time — and about 4,000 of the 20,000 agents are in Arizona.

Ed Ashurst calls himself a “65-year-old cowboy.” He manages this ranch and wants people to know what’s going on in this corner of the country.

“Before anything’s done on the border, the people who run this country — the president, vice president, Supreme Court, Senate, House, Department of Homeland Security — they need to decide that we actually have a national problem here. And they have not done that,” he says.

In 2010, Ashurst’s friend, a rancher by the name of Rob Krentz, was killed.

It was a well-known case, never solved, but many believed it was a murder committed by someone who had crossed over from Mexico illegally.

“Rob was murdered that way, about six miles, straight down there,” Ashurst says, pointing in the direction of a low ridge. “He left home early that morning to check some water lines to water cattle with, and at 10 o’clock he radioed his brother and said he saw an illegal alien, that it looked like he was injured and he was going to check him out. He asked his brother to call the border patrol. They never saw Rob again.”

That was probably the most painful border story for Ashurst and many in this small but tight-knit community of ranchers in southeast Arizona.

But the stories, as Ashurst says, are many. He often sees people-smuggling nearby, people moving in bunches into the country.

His house, outside of the border town of Douglas, has been robbed.

“Eight days ago there was a convicted felon standing right there in the door. He had been deported multiple times and he had done hard time in a prison in the United States,” says Ashurst.

And then there’s the drug smuggling. The attempts are brazen, says Ashurst. “We’re talking 1,200, 1,500 pounds of marijuana on each load.”

The smugglers use a power hack-saw to cut through the fence and get their contraband through, he says. Ashurst and other ranchers have witnessed it. Some of the smugglers are caught, but most are not, he adds.

“And we’re talking steel fences, places that are 10 feet high, places that are 13 feet high. It costs several million dollars a mile and it’s not stopping them.”

That’s why Ashurst is ambivalent about a longer, higher fence, the kind proposed by Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump. He’s not alone. A recent Arizona Republic poll found that most Arizona voters do not want a border wall between Mexico and the US.

Also: Latinos in Arizona are helping make it a swing state — but not just because of Trump

But Ashurst does think the US Border Patrol could be doing more.

In its Tucson area, some 262 border miles including most of the border in Arizona, the US Border Patrol reports that the agency apprehended more than 60,000 people crossing the border in the 2016 fiscal year. Of them, 5,877 were children crossing the border alone and 2,898 were people crossing in family units, meaning a child with a parent or legal guardian. The child and family migrants are sometimes from Mexico, but mostly from Central America — El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala.

I asked Ashurst if that agent we saw at the end of his road gave him any comfort.

“Sometimes there are multiple border patrol trucks there,” he says. “As you noticed, we’re 20 miles north of the border. You go south of here, and there will be no border patrol.”

There are differing views on that strategy, on whether agents should get close to the border, or stay farther away. Either way, Ashurst told me, the migrants are not being stopped. And much of the job of securing this area falls to Cochise County Sheriff Mark Dannels.

He doesn’t understand why the Border Patrol sees the border not as a line to be patrolled, but as a strip of land anywhere from 20 to 30 miles wide where smugglers can move almost undetected. He says the fact that the border is seen more as a zone means crime has penetrated Cochise County.

“To try and catch them 10 to 50 miles away from the border — that’s insane to me. As a local law enforcement officer for over 32 years of addressing problems here in Cochise County, if we know we have a drug house, we don’t go 10 miles from the drug house. We go to the drug house and we let them know we’re there to address it. I don’t understand why there’s not more at the border,” says Dannels.

And the violence has become personal for Dannels. His son, also a local police officer, was threatened by a member of a drug cartel. The next day, Dannels says, his son shot and killed the man who threatened him. The cartels then came after the sheriff.

“I had them in my backyard and my deputies and I chased him off. It’s a serious game we play down here,” he says.

Dannels has responded to the violence by giving out radios to ranchers so they can reach him faster in emergencies. They're supposed to be fully online next year. Ashurst has a radio, but for now it sits unused in a kitchen drawer. He’s waiting for the repeater stations to be put in service. Right now, he can’t use it to call for help.

Dannels and ranchers like Ashurst have spoken about their concerns with their federal representatives. But they don’t think Washington politicians see the gravity of the situation the way they do — and that’s what frustrates them.

I asked Ashurst if any of this would ever make him think about giving up ranching, about leaving this place.

“Maybe you should leave because that’s the thing that you people in Boston don’t get. Everybody thinks it’s my problem. It’s your problem,” he says. “Because they are coming to your neighborhood. They are already there. And you oughta get down on your knees and kiss my feet for staying here and slowing it down a little bit. I mean, no disrespect intended, but this is supposed to be America. Do I have to leave? So we give them 20 miles of America, and next year we give them another 20 miles.”

With additional reporting by Andrea Crossan and Angilee Shah.