In Arkansas, schools are supposed to teach in English. Here’s how one district gets around it.

Kennea Magdalene Fancy Kosmes, almost 3, is one of the youngest participants in Monitor Elementary’s pilot Pre-K Program. She has bilingual support in her class now, but soon she and her classmates will be expected to use only English in the classroom.

“This one just got here in March. She wasn’t enrolled,” says Carlnis Jerry, lifting an eyebrow and nodding her head toward a third-grader who is speaking in Marshallese.

It’s a Wednesday, and Viona Koniske is sitting with her classmate during a “lunch bunch” gathering in a converted supply closet at Parson Hills Elementary in Springdale, Arkansas.

Jerry had overheard Viona’s brother, a student at the school, speaking in the language of the Marshall Islands about someone else living in his household. She made a trip to the Koniske home and discovered the girl. She then helped Viona’s single working father figure out how to enroll his daughter in school mid-year — something he had been too confused about and too busy to do himself.

At school, Viona picks silently through the contents of her meal until Jerry speaks to her in Marshallese. Only then does she engage in a conversation. Together, they chat about what the girls eat at home (rice, tuna, instant ramen) and what they miss most about the Marshall Islands (their grandparents).

Jerry herself came to the US from the Marshall Islands in 1998 to attend college in Hawai’i. Now, she is one of about 10 full-time community liaisons in the Springdale school district working as an interpreter for Marshallese immigrant students and their families. Her role is essential: She picks up on things that other faculty and staff might not notice and conveys information that immigrant students and their families might not yet understand in English.

Anita Tomeing Iban was the first to do this kind of work. She came to Springdale in 1996 via Missouri, Kansas and Southern California.

“I know what it’s like, I’ve been there,” she says. “I’d write notes to my parents and tears would smear the ink.”

In 1997, Iban became an elementary level instructional assistant, then a parent community liaison doing translations and interpretations. In 2012, the Springdale school district hired two Marshallese community liaisons to serve the entire system. This made the role of liaison official and paved the way for schools to add their own resident community liaisons.

oembed://https%3A//www.youtube.com/watch%3Fv%3DmlgcjdCEiMw

At Helen Tyson Middle School across town, sixth graders in the Islander Club perform a traditional Marshallese dance during their study period. Their choreographer is another community liaison, Paul Lokebol.

Lokebol, 24, is Marshallese American and once attended Helen Tyson. After graduating from college in Missouri, he came back to Springdale and worked as a shipping specialist. He was recruited to the school by an administrator who heard he was back in town.

And he loves being back in these halls. After his students’ performance, Lokebol explains, “These kids are migrants, I mean, fresh off the boat, and they have no clue what’s going on. … From [the] time I walked in until now, I’ve seen a tremendous change in the lives of the students. I’m not talking about academic-wise, but also behavior-wise.”

In the Global Nation Exchange: Hear more from Lokebol and share your experiences in school in our Facebook discussion group.

Superintendent Dr. Jim Rollins says that the overarching objective of Springdale’s schools is: “Teach them all. All means all. It doesn’t matter if they come from across the street or across the ocean.”

Teaching them all is easier said than done.

The district’s data from 2014 and 2015 show that nearly half of Pacific Islanders don’t graduate. In the community, the graduation rate is between 71 and 89 percent over the same years.

Meanwhile, the Pacific Islander population in the schools has increased steadily by 200 to 300 students each year since 2009. In 2009, islanders represented 7 percent of 18,188 students. Last year, they constituted 12 percent of 12,472 students. Hispanic students make up the largest demographic group.

A Spanish-language spelling bee: Once, students were punished for speaking Spanish. Here, they are honored.

Language is the greatest and most obvious barrier for the Marshallese population, and Arkansas does not allow the use of languages other than English in its classrooms — the state has been English-only by law since 1987.

Arkansas is not alone in mandating unilingual education. Mississippi, North Dakota and North and South Carolina joined Arkansas with English-language laws of their own in 1987. California passed a law in 1998 that mostly eliminated bilingual education. Massachusetts and Arizona were both part of a dual-language movement in the 1980s, but have since moved to placing students in separate classes based on their English abilities. Today, only 19 states, including New York and the District of Columbia, accommodate languages other than English in the classroom.

Also: Why Massachusetts is rethinking its strict English immersion law for schools

Springdale provides English-Language Learner curricula, federally funded at $300 per student, and conducts a summer Family Literacy program that served approximately 200 immigrant families this past season. Monitor Elementary School launched a pilot Pre-K Center last year to acclimate multilingual toddlers to an English-only environment as early as possible. In addition to teachers, the center provides two Marshallese family service managers and Marshallese paraprofessionals who serve as instructional assistants.

But the sentiment is growing among Marshallese communities that their English education too often comes at the price of losing native language and culture. They believe that the real key to education for their students is to use and retain their native language while developing and practicing English.

JociAnna Chong Gum is one of just two Marshallese students currently attending the University of Arkansas. She remembers her disorientation when she was placed on the ELL track as a young student.

“I was pulled away from my classrooms to sit in a small room with other bilingual students and was basically taught to be fully Americanized,” she says. “I felt like I had to leave my culture at the door before I sat down to a teacher teaching me simple vocab and how to learn in a “regular” classroom. … I feel like that pushed me back. I still struggle to keep up with the Marshallese language.”

More from Arkansas: Most high schoolers worry about graduation. These students are also being challenged to save their culture

Marshallese linguist Alfred Capelle also believes that bilingual education is more effective for immigrant students than English immersion. He’s a proponent of “Long Term Maintenance bilingual education,” which provides instruction in two languages at least through sixth grade. Stanford researchers and the New York City Department of Education, which added 40 new dual-language programs throughout school system last year, also subscribe to a bilingual education model.

The Marshall Islands is also emphasizing Marshallese instruction in its own educational system, one of the most poorly performing in the Pacific. The country has had English-language education for its Marshallese-speaking population since World War II, when the US established a military presence there.

In Springdale, home to the largest population of Marshallese in the continental US, Capelle and his colleagues have called for the formation of bilingual charter schools. He says this could be done with support from the Customary Law and Language Commission, an initiative set up in 2004 in the Marshall Islands to fund educational programs that preserve Marshallese language and culture worldwide.

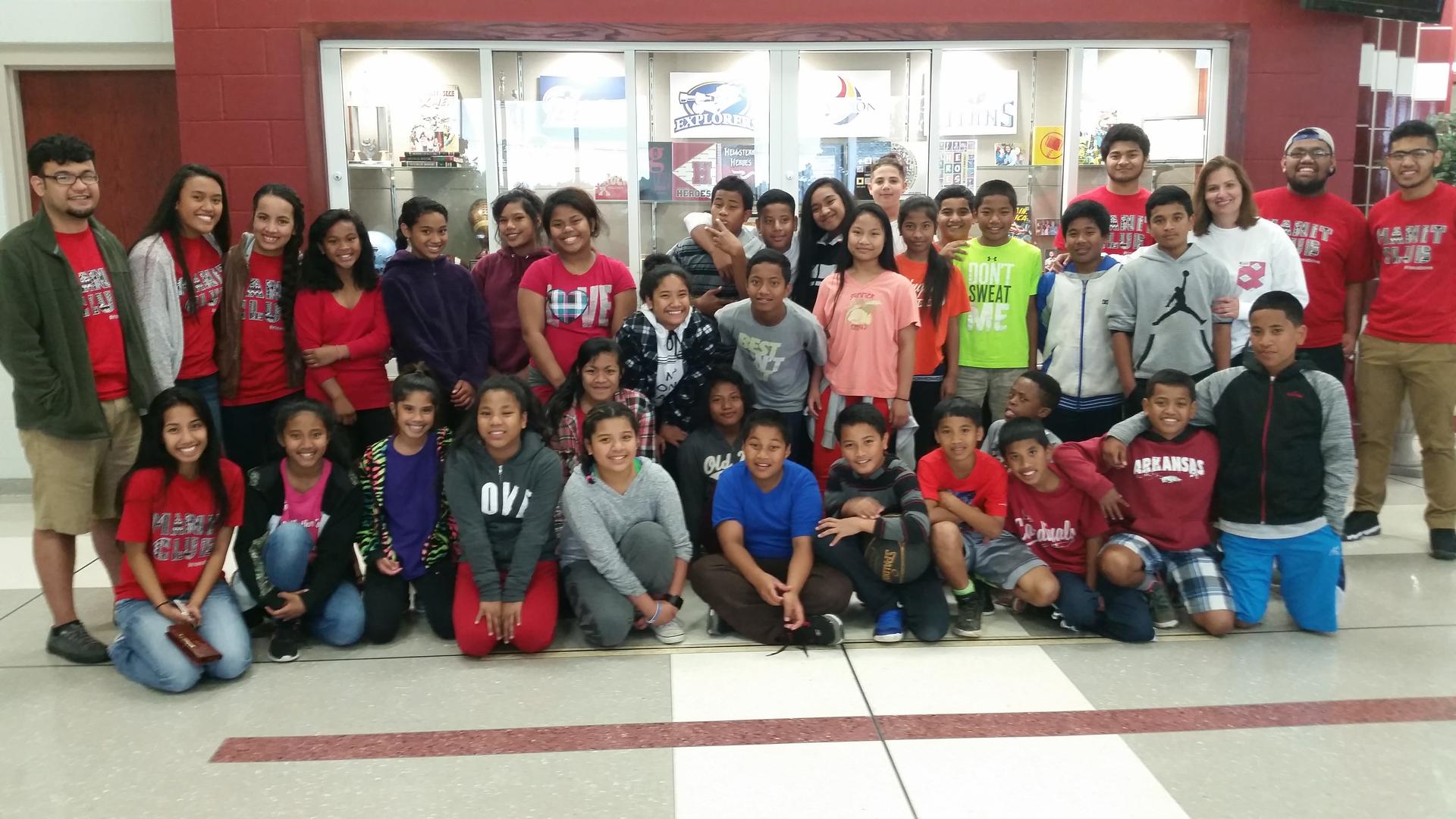

But many Marshallese American young adults are not holding their breath for brand new schools. Benetick Maddison, 21, is president of the Manit Club, a Marshallese college group that he founded to advocate for cultural empowerment and educational attainment. He has long been cynical about the Springdale schools district’s ability to adapt at the pace of its changing student population.

For one, he feels the US Department of Education’s Race to the Top program creates the wrong incentives for public schools to win federal money at all costs. In short, Maddison says the competitive structure of the bonus funding encourages schools to try to distinguish and then separate “good, smart kids from these other kids” rather than addressing the needs of all.

“We want these young kids to be successful in school but, of course, we also want them to stay rooted — know their language, culture and heritage,” Maddison says. “Staying rooted will be of huge benefit for them later in the future. But in order for anyone to know their culture and heritage, they must know the language first.”

This fall, the Manit Club is piloting a bilingual mentoring program in cooperation with Hellstern Middle School, also in Springdale.

Aside from providing moral guidance and inspiration, the mentors plan to speak in Marshallese and teach students about their culture and the importance of holding onto it. They aim to do this with a bilingual curriculum cobbled together from internet resources and brainstorming about what they would have wanted at that age. They want to stick with the students through high school and help them prepare for college and beyond.

Notably, half of about 20 of the Manit mentors had lost their own Marshallese skills through years of English-only instruction. So, Maddison relearned the language himself in order to help get his fellow mentors up to speed.

As a child, Maddison attended J.O. Kelly Middle School, which has a large Marshallese population. He remembers he was a de-facto community liaison for the staff while he was still a young student. He feels he knows firsthand what the students need, and is frustrated that other schools have not joined his program.

But he’s confident Manit Club’s program will succeed and that other schools will follow suit.

Chong Gum, who will also be a mentor, says, “This will definitely help them be better as students. They can have role models and actually know Marshallese who are in college.”

Maddison adds, “I believe that we can give them good words of advice because we, too, were once like them.”

Correction: We originally wrote that Carlnis Jerry moved to Hawai’i to attend high school. In fact, she went there for college.