These cochlear implants can break the silence for people with hearing loss

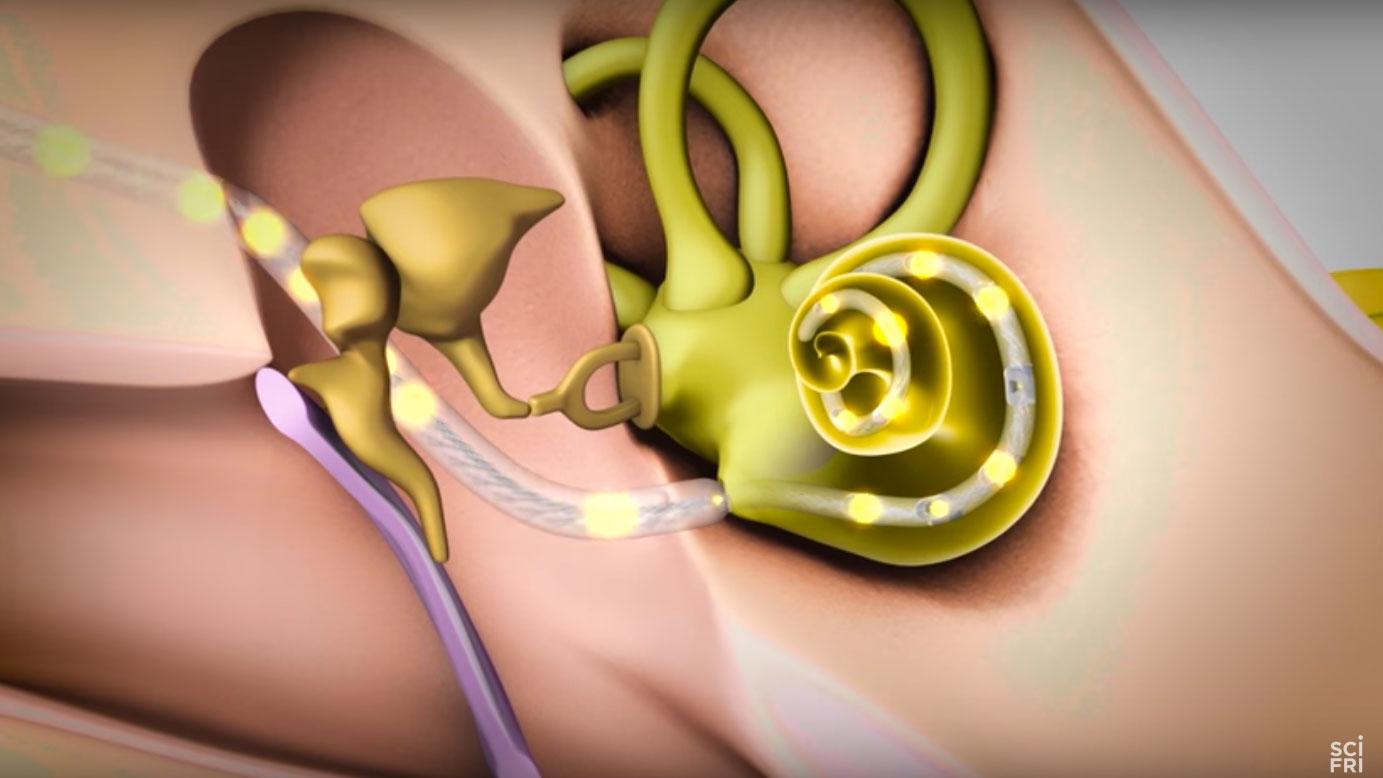

A screengrab from "Breakthrough: A Re-Sounding Remedy" showing a new technique to improve cochlear implants.

Allyson Sisler-Dinwiddie took her first hearing test as a young girl and walked out of the doctor’s office with hearing aids. But she never thought she would end up completely deaf — until 2004, when a car accident following her first year of graduate school accelerated her hearing loss. Six months after the accident, her world went silent.

“I’ll never forget this day because it was a Saturday,” Sisler-Dinwiddie says. “I had a little dog. She went to the door like someone was there. I couldn’t hear her bark at all. And at that point I realized, there’s no more hearing left. This is it.”

Sisler-Dinwiddie went on to become an audiologist and now works in pediatric audiology at Vanderbilt University. Part of her job includes checking the integrity of cochlear implants before surgeons insert the device. And at Vanderbilt, breakthroughs in the implants’ technology are helping patients young and old recover their hearing after severe loss — including Sisler-Dinwiddie.

oembed://https%3A//www.youtube.com/watch%3Fv%3DsLWg9af2Pg0

Rene Gifford, a hearing researcher and Sisler-Dinwiddie’s colleague at Vanderbilt, says that while hearing loss is a complex condition, it’s commonly caused by problems in the cochlea, the spiral-shaped chamber of our inner ear.

“Within this cochlea are three small chambers that are filled with highly conductive fluids,” Gifford says. “And then you have a number of hair cells, and their vibration creates this electrochemical reaction through the auditory nerve and then ultimately up to the brain.”

When the cochlear hair cells are dysfunctional or destroyed, they don't vibrate anymore — and the brain stops receiving messages about incoming sound. That’s where an implant comes in, using an array of tiny electrodes to stimulate auditory nerve fibers from within the cochlea itself.

“When I got my first cochlear implant, I went from nothing to a world that’s so far beyond what my hearing aids were ever able to provide,” Sisler-Dinwiddie says.

And yet, Sisler-Dinwiddie says, at first she heard a “very different kind of sound” after getting her implant. Similarly, other patients say cochlear implants have brought progress, but not perfection, to their hearing: Some describe background noises that arise when they speak, while others struggle to perceive music or conversation after the procedure. None of this comes as a surprise to Gifford, who says that the implant’s broad electrical stimulation can “smear” incoming sound frequencies and pitches.

“Cochlear implants are a miraculous technology, but when you stimulate an electrode, even though you’re wanting to stimulate just a narrow population of cells, what happens is it spreads,” Gifford says.

Gifford and her team looked for a way to combat the muddled sounds patients were experiencing. They landed on an idea to deactivate some of the implant’s electrodes based on an individual’s anatomy. Using a 3D reconstruction of the patient’s inner ear, researchers could evaluate the distance between each electrode and the auditory neurons that needed to be stimulated, keeping the electrodes that maximized hearing capabilities and turning off others. Sisler-Dinwiddie was one of the first volunteers to test the technique.

“I had heard this research was going on — I was here on staff,” Sisler-Dinwiddie says. “But as a patient, to hear that we’re going to ‘turn stuff off’ — even though I knew it was going to be for the best, I was very nervous.”

The technique worked. Sisler-Dinwiddie’s word recognition had been about 38 percent at her baseline. But once Gifford disabled two electrodes in Sisler-Dinwiddie’s cochlear implant, her word recognition jumped to 88 percent — overnight. “It’s like you took a pillow off my head,” Gifford remembers Sisler-Dinwiddie saying.

That was four years ago, and since then, there have been other success stories like Sisler-Dinwiddie’s. Both Gifford and Sisler-Dinwiddie hope to continue broadening the implant technology’s reach — including to more children, who Gifford says can respond even better to the technology than adults.

“The number of patients that have been able to take part in this, it has gone on and on,” Sisler-Dinwiddie says. “And they’re not going to stop here.”

This article is based on a video from PRI’s Science Friday, the first in a new series called “Breakthrough: Portraits of Women in Science.”