After Dilma, will Brazil keep up its massive corruption case?

Workers repair a tank of Petrobras oil company in Cubatao, Brazil, on April 12.

An average political conversation in Brazil these days invariably goes something like this:

Person 1: Brazil’s a mess, isn’t it.

Person 2: Yeah, what a mess!

Person 1: And how about this impeachment thing?

Person 2: Oh, I [loathed/loved] Dilma. I’m [happy/sad] that she’s gone.

Person 1: But the “Car Wash” investigation … that’s really important.

Person 2: Oh yeah. Whatever happens, we can’t shut that down. That would be a disaster for the country.

Person 1: You got that right!

Brazilians are divided over the impeachment of President Dilma Rousseff.

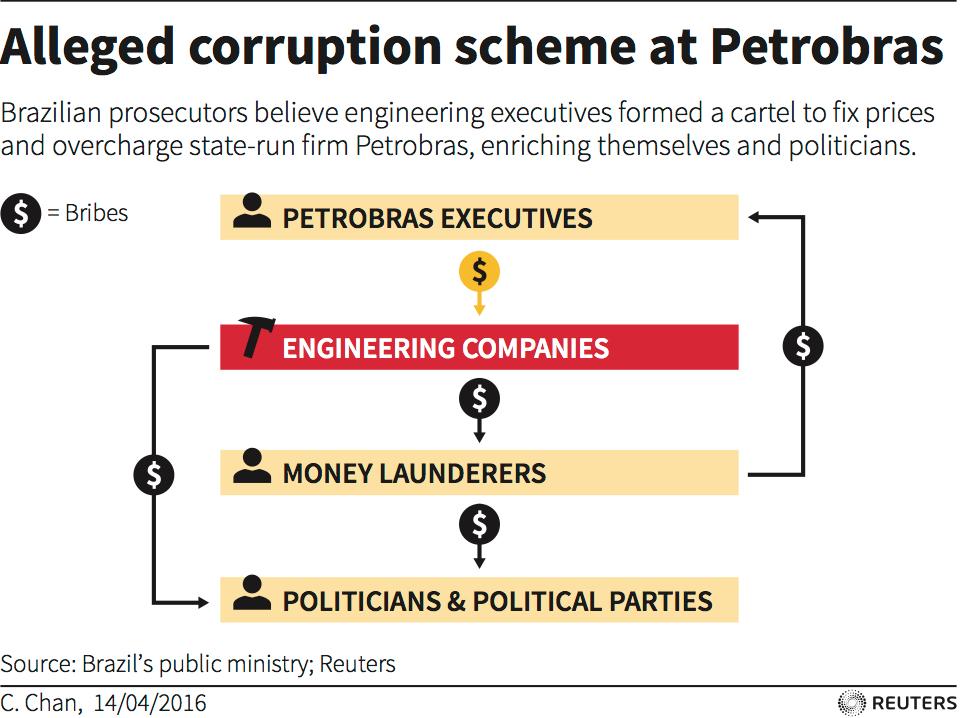

But if there's one thing the vast majority agrees on, according to polls, it's this: The two-year corruption case known as Operacao Lava Jato, or Operation Car Wash — the alleged multibillion-dollar bribery scheme ensnaring politicians and Brazil's major oil and construction companies — cannot be neutered or slowed down by the change in government.

There is a real threat that it could.

The new president, Michel Temer, himself is accused of requesting campaign funds linked to the illicit corporate kickbacks. Temer denies it.

A couple weeks after Temer took over from Rousseff in May, his new anti-corruption minister resigned along with another cabinet member after leaked private recordings suggested they wanted to oust Rousseff and derail the Car Wash investigations. Soon a third minister quit over allegations he was linked to the oil company scandal.

“There’s a good chance that Lava Jato starts to lose momentum,” said Brian Winter, vice president of policy at the Americas Society and Council of the Americas.

It’s hard to overstate how important Operation Car Wash has become, not just for the future of Brazilian politics, but for the Brazilian psyche.

“I think that Brazil has irrevocably changed,” Winter said. “The investigation has completely changed the risk-benefit analysis for an entire generation of Brazilian politicians and business leaders.”

Backroom deals

Although Rousseff was accused of trying to shield her political mentor from investigation, she herself is not personally implicated in corruption.

Many Brazilians see the investigation as one of the positives during her time in office, a period otherwise known for problems like the economy going boom to bust.

Publicly, her successor Temer has expressed unwavering support for the Car Wash investigation. The probe should be “protected against any interference that could weaken it,” he said in his first speech as interim president. He officially became president on Aug. 31.

But Temer and close allies have fought allegations aiming to link them to the Petrobras scandal. Rio de Janeiro-based political scientist Mauricio Santoro said he’s certain that Temer and his lieutenants will somehow attempt to defang the investigation.

The Temer administration may try to negotiate in secret with the Supreme Court to slow or stymie the prosecution of politicians allegedly involved in the scheme, Santoro said.

Federal politicians enjoy limited immunity that means they can only be tried in the Supreme Court. That leads to delays sometimes lasting years.

Other moves to thwart the investigation could happen in Brazil’s Congress — where more than half of lawmakers reportedly face criminal allegations, many of them for Car Wash crimes.

Legislators could attempt to quietly pass an amnesty for politicians convicted of corruption, Santoro said. Maybe they would hide the reform within other complicated legislation to avoid public attention.

Even so, Santoro said an amnesty for politicians would be like “a bomb going off” in Brazil and would bring thousands of protesters to the streets.

Whatever the tactic, he added, the outcome would be the same: a dismal rollback of years of progress in tackling the country’s endemic corruption.

“I think we’re going to see some very strange things in Brazil in the next few months,” Santoro said. “My general feeling is that we’re watching a movie without any heroes. It’s such a bad moment for the Brazilian political system.”

Not every analyst is so pessimistic, however.

Unwavering prosecution

Paulo Sotero, director of the Brazil Institute at the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington, DC, said the Car Wash investigation will survive attacks on it. Sotero, who met with Moro in Washington recently, said the crusading judge and his team are unwavering, and so is their support from the Brazilian public. That strength will carry them through, Sotero said.

“They are very determined,” he said. “[Moro] will use every opportunity to publicize what they do — this is a process that has to be conducted in the open precisely because of the need to maintain public support for what they are doing.”

Brazilian politicians, Sotero said, are also clearly on notice that this investigation is not to be messed with. In recent weeks, high-ranking politicians have scrambled to clarify past statements about the case and reassure the public that they want the probe to continue unfettered.

“At one level, these people fear for their reputations,” Sotero said. “Being against Lava Jato is politically not wise. It’s not good for you, not good for your reputation.”

Hobbling the investigation certainly would not be good for Temer’s reputation, said Shannon O’Neil, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations who specializes in Latin America.

Ostensibly, Temer has nothing immediately to lose, since he is barred from running for election for the next eight years for breaking campaign finance laws. But O’Neil thinks that when it comes to Car Wash, the former constitutional law attorney will be thinking more of his legacy than of his political future.

“If Lava Jato ends, it puts Brazil back 50 years,” O’Neil said. “And when you turn to the Brazilian history books 50 years from now, was Michel Temer the president who really helped modernize and push Brazil forward, or was he the one who took Brazil back to the old smoke-filled rooms and corrupt patronage system?”

She added: “His legacy, and where he falls in Brazilian history, is up for grabs.”

Ultimately, Temer and his posse will only be able to do what the Brazilian people let them do. But the experts watching Brazil worry that the nation has tuned out political debacle after months of chaos and uncertainty.

Three years ago, Brazilians took to the streets in record numbers to protest a failing economy and rampant corruption.

But as senators impeached the president last week in Brasilia, only a handful of demonstrators bothered to turn up in support or opposition of the process.

One thing all the experts interviewed for this story agree on: If Brazilians slip into apathy, corrupt politicians will be free to devise and execute a plan to save their hides. And that’s something very few people in Brazil — except for those directly implicated in the scandal themselves — want to happen.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?