What assimilation means to the ‘taco trucks on every corner’ Trump supporter

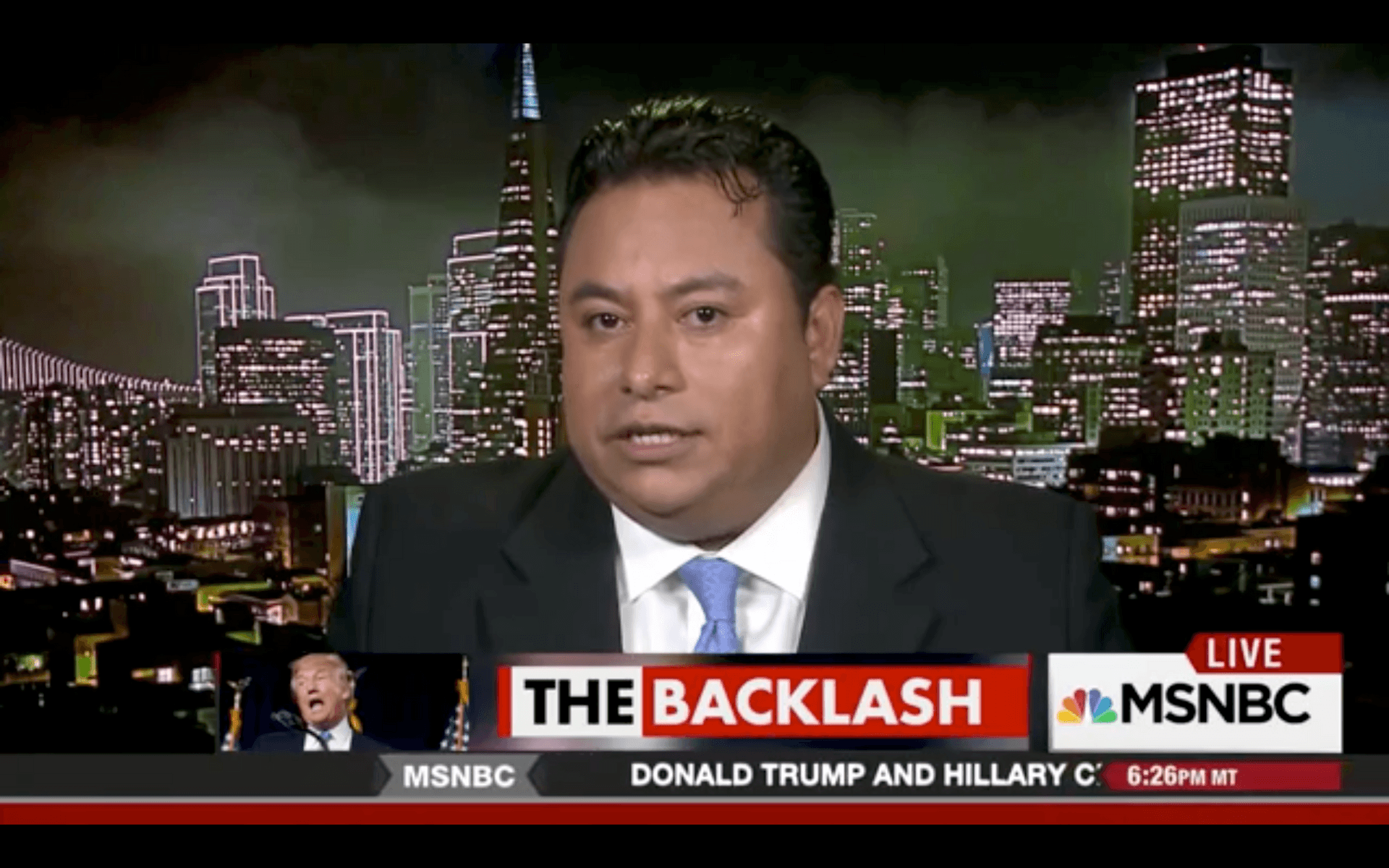

Marco Gutierrez has gotten a barrage of media attention since he appeared on MSNBC saying there would be "taco trucks on every corner" if Donald Trump didn't win the election.

Mexican American Marco Gutierrez says he doesn't regret saying, as a word of warning, that there would be "taco trucks on every corner" should Donald Trump lose the presidential election.

But he does wish he'd chosen better words to illustrate his point when he uttered the phrase on MSNBC earlier this week.

"Of course a lot of people's feelings were hurt, but it was a metaphor," Gutierrez says. "What I was trying to say — it was a poor choice of words to describe the lawlessness of illegal immigration into this country."

Gutierrez immigrated to the States when he was in high school. His parents were farm workers who got amnesty during the Reagan administration. He's been a staunch supporter of Trump since we first interviewed him back in June, and he attended the Republican National Convention as the founder of Latinos for Trump.

Since he used taco trucks to illustrate the dangers of illegal immigration, the internet has had a field day with Gutierrez's statement. #TacoTrucksOnEveryCorner was trending on Twitter Thursday night and NPR named it the #MemeOfTheWeek.

As of Friday, though, Gutierrez himself was unclear as to why the phrase stuck with people.

"If the third-world mentality continues, you're gonna have taco trucks outside the White House and pinatas — that's usually what I say," Gutierrez says. "It's sort of like a joke, but I'm just trying to describe that as Hispanics we are running away from a world that has problems and when we come here, we replicate those problems."

He says immigrants bring lots of beautiful things, too, but he feels failure to blend in well enough interferes with the country as a whole.

In five generations, he sees his family totally letting go of its Mexican heritage, and finally achieving integration.

But, "I don't think I'm ever gonna be fully [American]," he says. "The way I speak, my primary language, my understanding of the world was Mexico. But I talked to a therapist that told me that it takes about five generations to fully integrate, for the cultures to collide."

Gutierrez is being criticized for rejecting his culture and some tweeters have called him a "self-hating" Mexican.

"If my culture feels that I'm rejecting them, maybe they are rejecting me because I'm doing what I wanna do," he says. "Leaving your heritage has been a fight for me since I came to this country … because I think we have conflicting messages that we give our kids. As immigrants, we do not wanna integrate but yet we send our kids to school and we tell them to become attorneys, to become professionals, but yet we don't want to."

He's referring to the push immigrant parents typically make on their kids to pursue higher education even if the parents themselves work with their hands — say, on a farm, like Gutierrez's parents did.

He equates that push to leave blue-collar work behind — upward mobility — with assimilating into the established, white culture of the United States. He remembers a specific instance in high school that made him feel he wasn't good enough because he was poor.

The father of a Vietnamese friend of his had just bought a new house. Gutierrez was visiting, and he remembers a striking white carpet.

"I had never seen such a beautiful house, ever in my life," he says. "I didn't wanna go in because how beautiful it was, with the white carpet and everything. I felt like I was stepping on very high ground. I never felt the same again with [him], I couldn't even say hi to him anymore because I felt … it was out of my league to be his friend."

People who've lived in poverty — or just visited the imposing home of someone with lots of money — can likely relate. This isn't a rare experience. But Gutierrez internalized that feeling with his status as an immigrant, a Mexican American, and someone without financial resources.

Now, as an adult, he views coming up financially as "becoming white," in a way. And he thinks that's what people should try to do — like immigrants and black Americans have in the past, thinking "fitting in" was necessary to survive.