‘OK, Dad. Why did you kill Spanish in our family?’

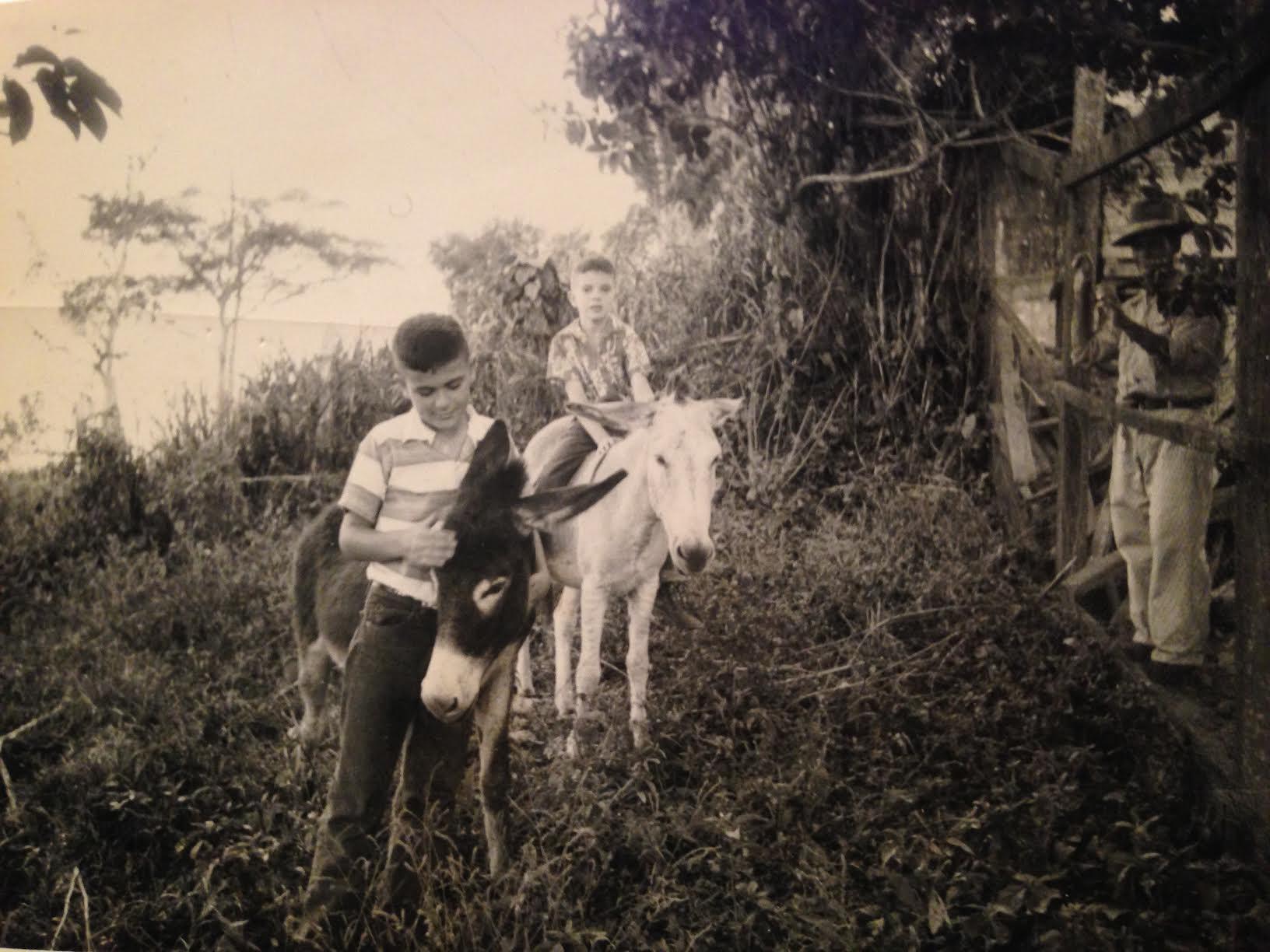

Brothers John and George Campbell ride donkeys in the forests of Segovia, Colombia.

My father killed Spanish years before I was born. Three years, in fact. 1978. The year my sister came into the world.

To the best of our knowledge that's when Spanish in our family stopped. But I never knew why.

My father is from Tegucigalpa, Honduras. He's a native Spanish speaker. No accent. It's this fluency that drives me crazy. He didn't pass down to us. As children, he only spoke to us in English.

The only fluent thing my sister and I can do — if you can even call it that — is this:

We can roll our R’s.

But that's it. Everything else is filtered through a thick American accent. Today, our Spanish is … pathetic. We can barely say basic introductions. It's embarrassing. And I think it's a major loss. Dad could have given us a key to communicate fluently in two languages. Instead, he installed a lock.

"I think he just, at that point in time, just didn't think that it was necessary, or beneficial, or interesting," says my sister, Kate.

But I wanted to know for sure. What were his reasons? Why let his mother tongue die? It's a scenario that plays out in plenty of families. How did it play out in my own?

I traveled across the US to find the answer. And I didn’t waste time.

"All right Dad, why did you kill Spanish in our family?"

That was my very first question.

All right, let me actually back up for a second. Because it will help you understand where Spanish in my family began. And that's 1923, the year my Grandma — Hortensia — came into the world.

She’s now 92 year old, and plays a pretty mean tango. She's a ball of joy. Always has been. At her house she takes out a scrapbook and points to a picture. It’s of a woman, wearing a floral dress and carrying a classical guitar. There's a red rose in her hair. I ask, playfully, who it is:

“It’s me when I was much younger,” she says to me in Spanish. “And I was playing the guitar!”

Just like my dad, Grandma was born in Honduras. But her parents died young. She wound up in an orphanage. And yet, she only really remembers good times.

"We pray. We laugh. We sing. We were so happy. To me, they were my family," she says.

The orphanage got a lot of financial help from a local dentist. He also gave the kids jobs. And Grandma got one as a dental assistant.

"That’s the way I met your Granddad," she says.

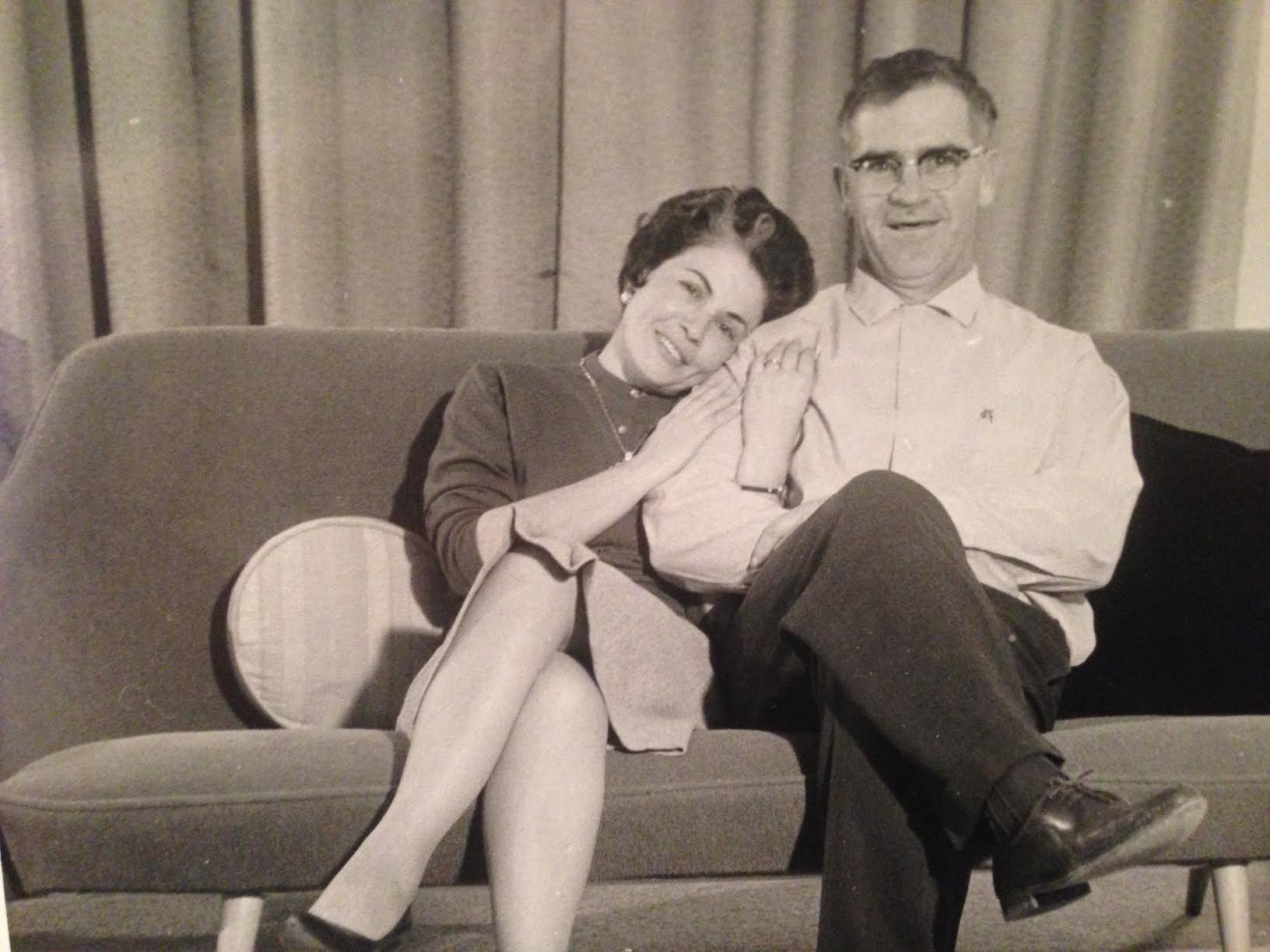

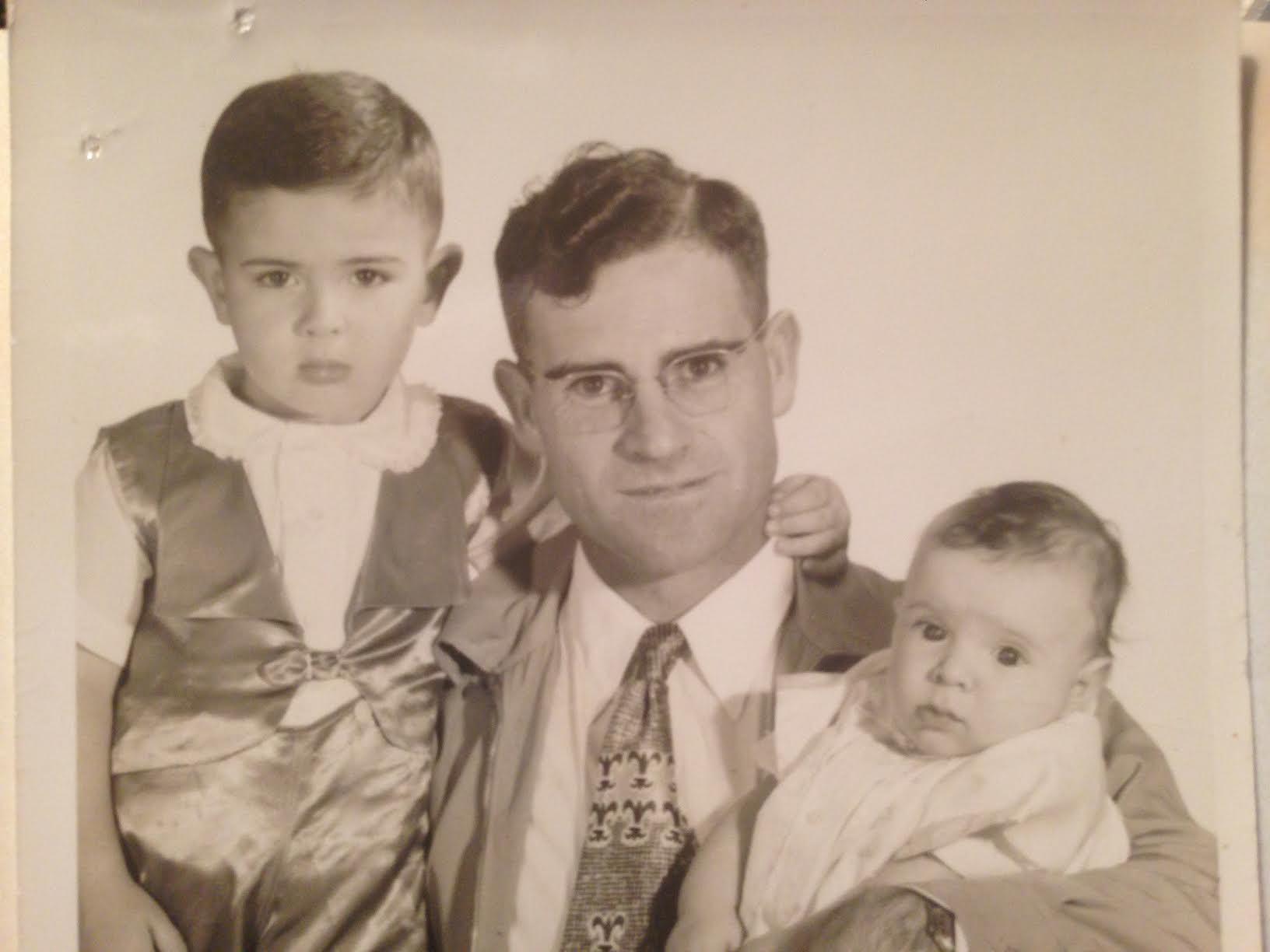

It was a love story based on bad teeth. Granddad was American, from Colorado. He’d come to work in a mine as an electrician. He and Grandma hit it off. They married, and had two boys. My father, John, and my uncle, George.

The family moved a lot. They went from mining jobs in Honduras to El Salvador to Colombia, and eventually landed in Chile.

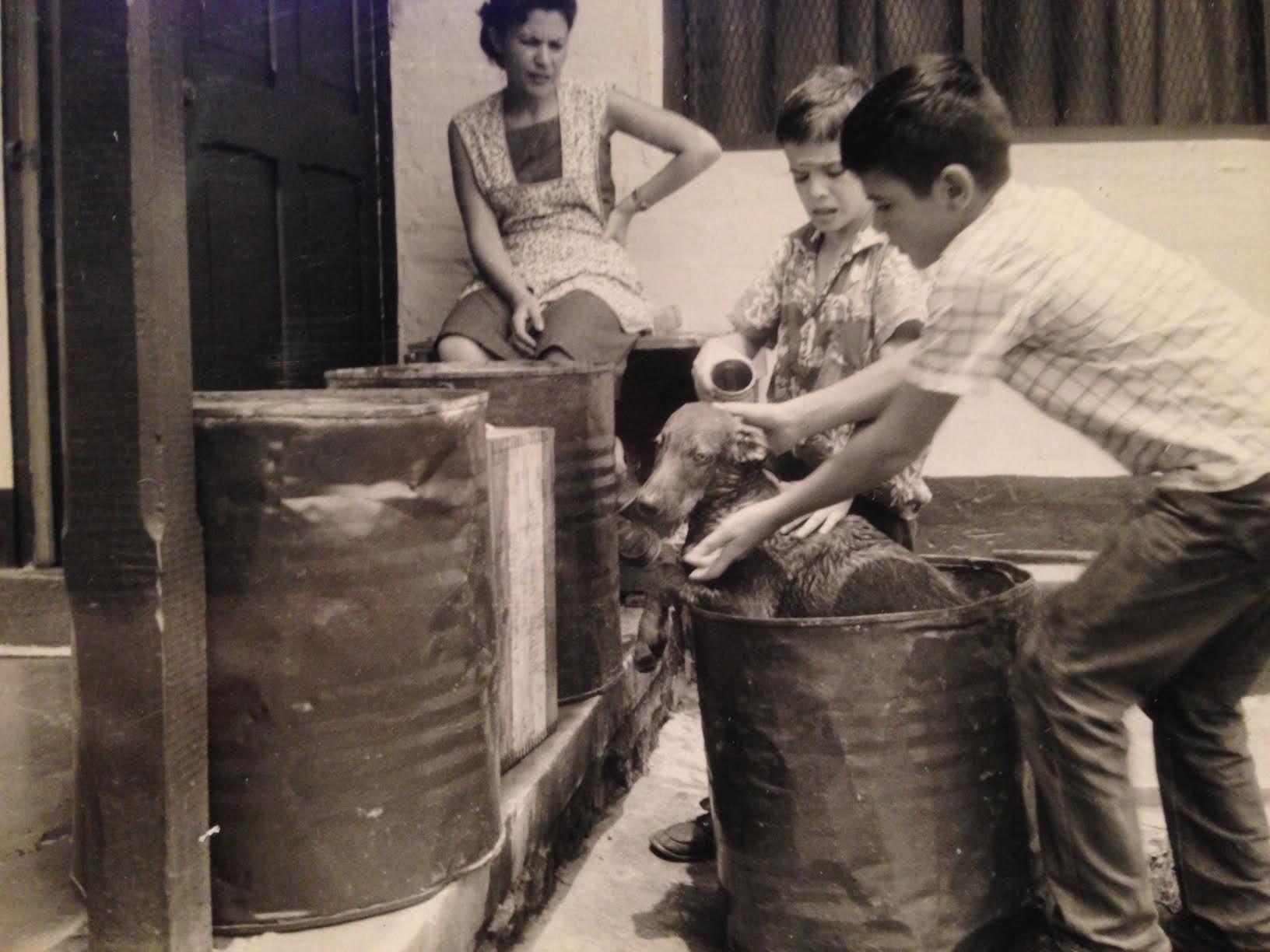

Spanish was a must. Everyone spoke, including the kids — Dad and his brother. So you’d think as kids they would’ve talked to each other in Spanish. I mean, that the language that surrounded them. Not so. I found that kinda odd. And so did Uncle George.

“You’re bringing up an interesting point,” he says. “John and I never really sat down and had a conversation in Spanish just between the two of us.”

Dad has no clue why.

"I don't know?" he says.

But Uncle George thinks it may have been an order from his dad — the electrician from Colorado.

"I remember where it became an issue is when Dad brought John and Mom and myself up to Colorado to introduce us to his family and none of us could communicate in English,” he says. “I think he realized then, 'Oops, we better get these kids speaking English.’ So at that point, I believe, that when they laid down the rule. Dad would speak to us in English and mom in Spanish."

Sounds ideal. Fifty percent Spanish, 50 percent English. Except, pretty soon English took the lead. The mining company my grandfather worked for was British. They ran the schools. So all the instruction was in English, aluminium and all.

All these facts I knew. But then my dad told me a story.

As I heard it, I thought maybe I found the reason why Spanish died in our family.

"One time in Colorado we stopped at a little restaurant in little town to get some lunch. We were the only ones in there. And as the waitress started to come over I said something to Mom in Spanish. And then the waitress just stopped and turned around,” he says. “We sat there and sat there for like 10 minutes. And the waitress and the cooks just sat back by the counters just looking at us. Finally Dad realized it. He said, 'OK, let's go.'"

It's so strange to hear this. Because when you see Dad you see a Caucasian man. So it's crazy to know he had to deal with stuff like this all due to language.

But Dad was quick to stress this was the only time something like that happened to his family. And then he doubled-stressed the experience had zero influence on why he didn't teach me Spanish.

In fact, if there is a constant in my family it's that Spanish is beloved.

“It's melodic. It's poetic. It's expressive. It's a deeper beauty. There's something about the language that resonates deep down inside,” says Uncle George.

He’s right. Whenever I listen to Dad speak it, even the most mundane things sound beautiful to me, even if it’s something as simple as asking Grandma if she wants to grab dinner at a local Mexican joint.

Which gets us back to where we started (my very first question).

"All right Dad, why did you kill Spanish in our family?"

Getting Dad to give me a satisfying answer took close to two hours. If I can break down his reasons they went like this, in ascending order of importance:

—His wife, my mom, doesn't speak Spanish.

—In the 1980s it wasn't a big thing to teach kids language early. Dad honestly thought we could pick it up in high school and be fine.

—But the biggest reason, and the one that changed the way I look at him, is honestly one that I'm still trying to grasp. Dad doesn't feel like he's fluent.

In fact, by the time he had us kids, Spanish was far away in his past.

"By that time, remember, last time I'd had been around Spanish was 8th grade when I moved away from Chile,” he says. “There was no high school down there so they sent me up to a boarding school. So it really stopped at eighth grade. So my Spanish is really … it's really true if you don't use it you definitely lose it.”

The choice to pass down a half-assed language wasn't something he wanted, or felt comfortable doing. And even the couple of times he tried to talk to me as a small kid, I was …

“Annoyed,” he says.

Dad could only imagine one scenario where he might have felt comfortable enough to do it.

"I think probably if both my parents were Honduran and I came to the United States in my twenties or afterwards, then I bet it would probably have been easier to speak to you in Spanish," he says.

The only time Dad really uses his Spanish now is with Grandma. And remember the part about her being an orphan? Well, that means he has no other Spanish-speaking relatives. Ones that he knows. The pool shrinks.

The consequence of this is that every one in my family–Dad, Uncle George, and even Grandma — are forgetting the language and speaking Spanglish.

"Grandma will ask, 'Can you parkiar the car nearby?' And I'll ask, 'parkiar?'” he says. “I think a lot of people that live here use those words. They're just adopting the English word for it and giving it a Latin twist.”

So a dog becomes a “dogito.” A match transforms from a “fósforo” to a “matcha.”

Dad wishes he didn't have to create such words. He wishes he could speak more fluent Spanish. He’s met other people like him. When he still served in the US military he met a fellow solider whose parents were from Mexico. They quickly hit if off and started talking to each other in Spanish.

"We were both bemoaning the fact that we could not carry on a college level, philosophical conversation in Spanish,” he says. “Our vocabulary was so stunted.”

I could tell Dad is a little frustrated at his own lack of fluency. And it changed the way I look at him. It's like your whole life you think someone is awesome at something, but in reality they're not all that great.

And yet … I still couldn't let it go.

"There's this chagrin,” I tell him. “No, it's a grudge I hold against you.”

"Well, again, I don't know. It's like … You know, perhaps I should have hired a Spanish tutor but it was … Um … I don't know. Good question, I don't know?”

"That wasn't a question,” I respond. “It was a statement. I'm holding a grudge against you.”

"Well, I can't worry about that."

"It's something I'll have to deal with myself?"

"Yeah. You're gonna have to get yourself an appointment. Get a therapist and work your way through it.”

And that’s when everything crystalized in my head.

We blame out parents for a lot of our failures in life.

Yet in this instance, it was my own damn fault.

Sure, Dad didn't teach Spanish to me as a kid. But when I studied it in high school and college I had an advantage over most of my peers. I could practice my Spanish with a native speaker whenever I wanted.

Yet for some reason, I never picked up the phone.

My father didn’t kill Spanish.

I did.

Spanish — though — sprang back to life. My sister had a baby girl, Eva Hortensia. They’re already practicing their “Holas.” But my sister is still leery of passing down a language she herself has trouble speaking.

"Maybe, my job isn't to teach Eva Spanish,” she says. “Maybe my job is to help Eva obtain an appreciation for the desire to speak Spanish because of her family history."

My dad, however, is gung ho. There are language immersion programs in schools where my sister lives. He’s pushing to enroll Eva. I wouldn't say it's a total a do-over. He just wants Eva to speak another language, and Spanish would be nice.

"I mean the best time is right now,” he says. “You know, she's two years old. Right now is the best time to really learn it."

So Eva is may be our Spanish savior.

That’s a lot of pressure on a 2 year old.

But it’s not all on her.

Because anyone can learn — or revive — their family language.

All you gotta do is try.

"Halo?”

"Hola, Abuelita, Coma estas?"

“Bradley, coma estas?”

“Vamos a practicar Español?”

“Sí!”

———

PODCAST CONTENTS

00:25 “Does your dad speak another language?”

01:30 US Housing and Urban Development Secretary Julian Castro’s relationship with the Spanish language.

2:00 Bradley Campbell’s dad “killed” Spanish

3:25 “Rrrrrr”

4:50 The first time Bradley’s dad was called a beaner.

5:30 1923, the year Hortensia Maria was born.

7:20 Dad and Uncle George always spoke English to each other.

8:30 A restaurant stop in Colorado.

10:20 Some background on Bradley’s hometown, Dallas, Oregon.

12:05 Dad doesn’t feel like he’s fluent in Spanish.

13:40 Spanglish rears its head.

14:15 In the US military Dad meets a guy from Mexico.

15:25 Bradley still holds a grudge.

17:00 Spanish springs back to life.

18:02 A phone call to Abuelita.

19:52 Bradley tells Nina and Patrick about his visiting his Dad’s home in Chile.

22:23 The person delivering this week’s credit for the National Endowment for the Humanities is a pretty well-known guy. Recognize the voice? Let us know at Facebook or Twitter.

MUSIC HEARD IN THIS EPISODE

“Dramamine” by Podington Bear

"The Dead of Winter" by Will Bangs

"I'm So Glad That You Exist" by Will Bangs

“Alguien” by Cucu Diamantes

You can follow The World in Words stories on Facebook or subscribe to the podcast on iTunes.