Calling over boat noise is making endangered orcas hungrier

Though the killer whale (orca) species is not endangered globally, the population residing off the Pacific Northwest’s coast is.

In the Pacific Northwest, a nautical hub for ships and naval training, endangered orcas and other marine life are struggling to be heard over the noise.

While orcas are not endangered globally, the orca population near Seattle is. To communicate above the din of ocean traffic and industry, orcas must increase the volume of their calls. This extra effort requires them to eat more, and could be stressing the whales, according to new research at NOAA’s Northwest Fisheries Science Center in Seattle.

“The question is, OK, they do it, but so what? What are the biological consequences of them doing this,” asks Marla Holt, a NOAA biologist. To answer that question, Holt and her NOAA colleague, Dawn Noren, studied captive bottlenose dolphins.

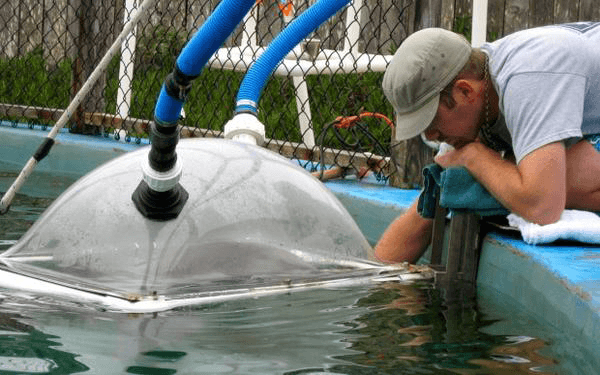

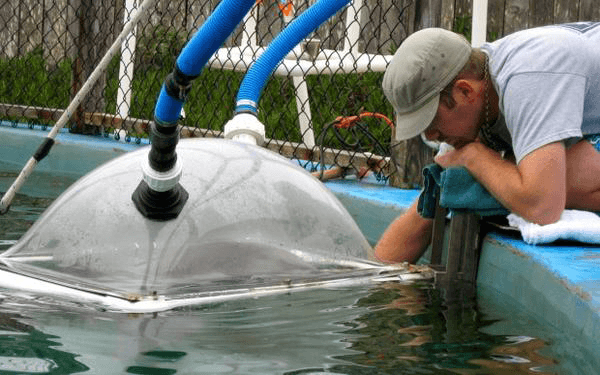

In an experiment, a dolphin swims into a floating, plastic, helmet-like device positioned over its head. Then the trainer asks it to make its normal whistling call for two minutes in order to claim a fishy reward.

Dawn Noren measured how much oxygen the dolphin used during those two minutes. “By knowing oxygen consumption, you can determine metabolic rate — or how much it costs you to work, or work harder,” Noren explains.

Then the trainer asked the dolphin to pump up the volume. Making the louder call takes more energy. Holt and Noren found that when the dolphin was whistling harder and louder, its metabolic rate rose by up to 80 percent above normal resting levels. Like people, when their metabolic rate goes up, they burn more calories, so they have to eat more.

“If you have multiple incidences in which you’re increasing your vocals to compensate for a noisy environment, you could have some increased need to find more fish,” Noren says. According to Noren and Holt, when wild orcas are around loud ships, they increase the volume of their calls by the same amount, or more, than the dolphins in their lab. This could mean that wild orcas need to eat more salmon to make up for the calories they’re burning to vocalize more loudly around big ships.

“For animals that are maybe just getting by, or not really getting by, we could say how much more fish it would cost an animal if it was disturbed that much more,” Holt says.

As the region considers proposals to expand coal and oil shipments, as well as Naval training activities, this research could be used to calculate specific impacts on marine mammals like endangered killer whales. There are just 81 of them left along the Seattle coastline.

This article is based on a report by Ashley Ahearn of Earthfix. The story aired on PRI’s Living on Earth with Steve Curwood.

In the Pacific Northwest, a nautical hub for ships and naval training, endangered orcas and other marine life are struggling to be heard over the noise.

While orcas are not endangered globally, the orca population near Seattle is. To communicate above the din of ocean traffic and industry, orcas must increase the volume of their calls. This extra effort requires them to eat more, and could be stressing the whales, according to new research at NOAA’s Northwest Fisheries Science Center in Seattle.

“The question is, OK, they do it, but so what? What are the biological consequences of them doing this,” asks Marla Holt, a NOAA biologist. To answer that question, Holt and her NOAA colleague, Dawn Noren, studied captive bottlenose dolphins.

In an experiment, a dolphin swims into a floating, plastic, helmet-like device positioned over its head. Then the trainer asks it to make its normal whistling call for two minutes in order to claim a fishy reward.

Dawn Noren measured how much oxygen the dolphin used during those two minutes. “By knowing oxygen consumption, you can determine metabolic rate — or how much it costs you to work, or work harder,” Noren explains.

Then the trainer asked the dolphin to pump up the volume. Making the louder call takes more energy. Holt and Noren found that when the dolphin was whistling harder and louder, its metabolic rate rose by up to 80 percent above normal resting levels. Like people, when their metabolic rate goes up, they burn more calories, so they have to eat more.

“If you have multiple incidences in which you’re increasing your vocals to compensate for a noisy environment, you could have some increased need to find more fish,” Noren says. According to Noren and Holt, when wild orcas are around loud ships, they increase the volume of their calls by the same amount, or more, than the dolphins in their lab. This could mean that wild orcas need to eat more salmon to make up for the calories they’re burning to vocalize more loudly around big ships.

“For animals that are maybe just getting by, or not really getting by, we could say how much more fish it would cost an animal if it was disturbed that much more,” Holt says.

As the region considers proposals to expand coal and oil shipments, as well as Naval training activities, this research could be used to calculate specific impacts on marine mammals like endangered killer whales. There are just 81 of them left along the Seattle coastline.

This article is based on a report by Ashley Ahearn of Earthfix. The story aired on PRI’s Living on Earth with Steve Curwood.