When a bomb goes off in Lebanon, Syrians suffer

A boy stands near tents inside an informal settlement for Syrian refugees in Taanayel, Bekaa valley, Lebanon in January.

Abdo was woken up in the middle of the night by loud raps on the metal door of his one-room apartment. For Syrian refugees in Lebanon, midnight visitors are rarely good news.

It was the police. They gathered everyone from the building — all of them Syrian — in a dark alleyway behind the house, and demanded to see their papers. Then the humiliation began.

“The police officers tortured us,” says Abdo, who withheld his real name for fear of repercussions. “They taught us a sports lesson at night. Push-ups, squatting position, standing on one leg, forbidding us to sit down. And they hit us. They slapped us. That went on from 12:30 till 2 a.m.”

Abdo’s ordeal is one that is becoming increasingly familiar to Syrian refugees in Lebanon in times of upheaval: When a terror group from Syria carries out an attack on Lebanese soil, Syrians in the country suffer as a result.

A familiar routine

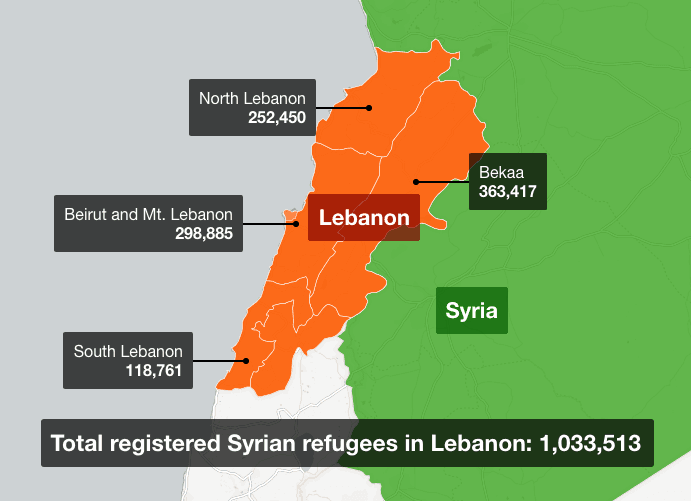

Lebanon is the nation with the world's highest number of Syrian refugees in proportion to its population. More than 1 million reside here, amounting to around 1 in 5 people. The influx has put a tremendous strain on the country's economy and security apparatus. With no prospect of a resolution to the conflict next door, neither refugees nor locals know when the crisis will end. This has led to nervousness on both sides.

In late June, two weeks before the raid on Abdo’s home, a wave of suicide bombers struck another Christian village, Al Qaa, on the Syria-Lebanon border, killing five people and injuring more than a dozen others.

In what's become a grim routine, authorities responded to the attacks by carrying out raids against Syrians, arresting hundreds. Since then, the Lebanese Army has raided refugee camps across the country, including in Hermel and Al Qaa. Forty Syrians were arrested this week in one such operation, which the army says is precautionary. Reports of attacks and abuse against Syrians in Lebanon spiked after the bombings. The authorities implemented new curfews in largely Syrian communities, and tightened other curfews already in place.

Lebanese Interior Minister Nuhad Mashnuq warned there would be “disciplinary measures” to combat a “rise in the abuses committed by members of the police in several municipalities concerning Syrian refugees.”

Even before the raid on his home, Abdo — a plumber from the province of Aleppo — noticed the change in the Christian village of Amchit, where he lives.

“Before everyone treated us well. Now, sometimes when it’s hot, the men go and stand on the street, cars that pass by curse us and ask us why we’re standing outside. It’s hot, we’re taking some air, we don’t mean anything else,” he says.

“Because of what’s happening in Syria, they think that any Syrian might be a terrorist,” says a Syrian worker in Lebanon.

“Because of what’s happening in Syria, they think that any Syrian might be a terrorist. And we’re not like that. Personally, I’ve been going to Lebanon for 10 years. I never bothered anyone or hit anyone and no one has ever hit me or anything.”

Spillover

Since the beginning of the civil war in Syria in 2011, Lebanon has struggled to stop the conflict from spilling over its border. The small country has suffered from a wave of bombings carried out by Sunni Muslim militant groups, such as al-Qaeda and ISIS, targeting largely Shiite Muslim areas. In one of the deadliest attacks, 43 people were killed in south Beirut last November. In 2014, militants briefly overran the border town of Arsal.

Although Amchit is on the other side of the country from the Syrian border, nestled on the coast looking out to the Mediterranean, residents here fear that these attacks could spread to their town. Many perceive any Syrian as a potential threat.

Just around the corner from Abdo’s home, yards away, is a hair salon owned by Sami Sakkr. We speak one day after a man drove a truck through crowds of people celebrating Bastille Day in Nice, France, killing 85.

“Yesterday in France, who imagined that a terrorist would come and hit people with a truck?” he asks. “If we weren’t cautious, that would have happened to us maybe.”

Sakkr and the other predominantly Christian residents in Amchit fear that ISIS fighters lurk among the refugees in the town.

“All the Syrians here support [Jabhat] al-Nusra,” he says, referring to the al-Qaeda-linked Syrian rebels that recently cut ties with its parent organization. He adds that he’s not the only one suspicious of the Syrians. Being a hairdresser, he hears from a lot of locals.

“They say, ‘Let the police fucking remove them. Let them piss off all of them together! We don’t want anyone at all!’”

It didn’t used to be this way. Syrians have been living and working in Amchit for years. Before Syria's war, hundreds of thousands of them came to Lebanon to find work and send money home — Abdo among them.

“When the war started, we got scared and careful.”

On the day I arrive in the town, dozens of Syrians are lining the road, repaving the entire stretch throughout the town. Every construction site is manned by Syrians.

But the war has changed things, Sakkr says.

“I used to see them in front of my shop every day in the evening. You were able to find 40 or 50 people, and they stayed till 10 or 11 p.m. But when the war started, we got scared and careful.”

The unknown

Since the war began, the number of Syrians in the country has increased dramatically, transforming small towns like Amchit.

“There are too many,” says Marwan, a shopkeeper who serves dozens of Syrians every day. “In every area, the numbers of Syrians are multiplying. You used to see 1,000 and that’s not much, but now you see 2,000 or 3,000. There are strangers, new faces, new looks.”

“There’s always fear. Whenever there’s an explosion, it paralyzes the whole country,” he adds.

Marwan says there is a distance between the Syrians and the local Lebanese community, partly because they are from different backgrounds and religions.

“When Syrians come to my mini-market, my relationship with them is like my relationship with any customer of mine. You interact with them, you feel empathy towards them. But there are no visits, and no good communication between us,” he says.

“There’s still some fear of bonding with that person because of their situation in Syria. They have some sort of racial sectarianism. They say ‘We are Muslim, this one is Christian,’ and he stays away from you.”

Some people also point to history to explain their distrust. The Syrian Army occupied Lebanon throughout its 1975-1990 civil war, and beyond. It ruled the country with an iron fist, assassinating opponents and dominating political life until mass protests forced its withdrawal in 2005. The dreaded mukhabarat — secret police — were feared by rich and poor alike.

“We have felt like this since Syrians were [occupiers] in our country, and it’s not over yet,” Marwan says. “Even though we greet and kiss someone, we still feel fear and alertness.”

Life under curfew

Abdo first came to Lebanon 10 years ago, and until recently traveled back and forth. The war ended that. His wife and three young children came to live with him in Lebanon for a short while, but they were unable to obtain the necessary papers to stay. Now, Abdo sends money home.

He is a plumber by trade, but he takes any work he can get. Similar to migrant day laborers across the United States, Syrians in Amchit wake up early and wait in a square in the middle of town for construction site managers to drive through and pick up workers. He spends the daylight hours doing backbreaking work. When he finishes work at around 5 p.m., he rushes to buy food for dinner before the curfew takes effect at 7 p.m. (there are signs around town to remind him). Then, he and 30 others in his small building are inside for the evening, Abdo in a room not much bigger than a prison cell. He has a small television and a camping stove to cook with. The men pass the time drinking tea and watching movies.

“If we get caught by a police officer or someone in the street, they curse us and ask us why we are out. They ask us how many times they’ve told us about the curfew, ‘You should go buy your stuff before that,’” says Abdo.

“This is our life here. I’ve been here on and off for a long time. I know the Lebanese regulations as I know my kids and my house.”

Abdo says the atmosphere now for Syrians like him is so bad that he would return home if he could.

“But I cannot do it before I improve my situation. Winter is near, so life becomes harder, you need a heating stove, fuel, a heater and wood.”

As I leave the village, I pass Abdo standing nervously on the road close to the door of his home. He is too afraid to wait in the main square any more, and so today he did not work.

Richard Hall reported from Amchit, Lebanon.

Abdo was woken up in the middle of the night by loud raps on the metal door of his one-room apartment. For Syrian refugees in Lebanon, midnight visitors are rarely good news.

It was the police. They gathered everyone from the building — all of them Syrian — in a dark alleyway behind the house, and demanded to see their papers. Then the humiliation began.

“The police officers tortured us,” says Abdo, who withheld his real name for fear of repercussions. “They taught us a sports lesson at night. Push-ups, squatting position, standing on one leg, forbidding us to sit down. And they hit us. They slapped us. That went on from 12:30 till 2 a.m.”

Abdo’s ordeal is one that is becoming increasingly familiar to Syrian refugees in Lebanon in times of upheaval: When a terror group from Syria carries out an attack on Lebanese soil, Syrians in the country suffer as a result.

A familiar routine

Lebanon is the nation with the world's highest number of Syrian refugees in proportion to its population. More than 1 million reside here, amounting to around 1 in 5 people. The influx has put a tremendous strain on the country's economy and security apparatus. With no prospect of a resolution to the conflict next door, neither refugees nor locals know when the crisis will end. This has led to nervousness on both sides.

In late June, two weeks before the raid on Abdo’s home, a wave of suicide bombers struck another Christian village, Al Qaa, on the Syria-Lebanon border, killing five people and injuring more than a dozen others.

In what's become a grim routine, authorities responded to the attacks by carrying out raids against Syrians, arresting hundreds. Since then, the Lebanese Army has raided refugee camps across the country, including in Hermel and Al Qaa. Forty Syrians were arrested this week in one such operation, which the army says is precautionary. Reports of attacks and abuse against Syrians in Lebanon spiked after the bombings. The authorities implemented new curfews in largely Syrian communities, and tightened other curfews already in place.

Lebanese Interior Minister Nuhad Mashnuq warned there would be “disciplinary measures” to combat a “rise in the abuses committed by members of the police in several municipalities concerning Syrian refugees.”

Even before the raid on his home, Abdo — a plumber from the province of Aleppo — noticed the change in the Christian village of Amchit, where he lives.

“Before everyone treated us well. Now, sometimes when it’s hot, the men go and stand on the street, cars that pass by curse us and ask us why we’re standing outside. It’s hot, we’re taking some air, we don’t mean anything else,” he says.

“Because of what’s happening in Syria, they think that any Syrian might be a terrorist,” says a Syrian worker in Lebanon.

“Because of what’s happening in Syria, they think that any Syrian might be a terrorist. And we’re not like that. Personally, I’ve been going to Lebanon for 10 years. I never bothered anyone or hit anyone and no one has ever hit me or anything.”

Spillover

Since the beginning of the civil war in Syria in 2011, Lebanon has struggled to stop the conflict from spilling over its border. The small country has suffered from a wave of bombings carried out by Sunni Muslim militant groups, such as al-Qaeda and ISIS, targeting largely Shiite Muslim areas. In one of the deadliest attacks, 43 people were killed in south Beirut last November. In 2014, militants briefly overran the border town of Arsal.

Although Amchit is on the other side of the country from the Syrian border, nestled on the coast looking out to the Mediterranean, residents here fear that these attacks could spread to their town. Many perceive any Syrian as a potential threat.

Just around the corner from Abdo’s home, yards away, is a hair salon owned by Sami Sakkr. We speak one day after a man drove a truck through crowds of people celebrating Bastille Day in Nice, France, killing 85.

“Yesterday in France, who imagined that a terrorist would come and hit people with a truck?” he asks. “If we weren’t cautious, that would have happened to us maybe.”

Sakkr and the other predominantly Christian residents in Amchit fear that ISIS fighters lurk among the refugees in the town.

“All the Syrians here support [Jabhat] al-Nusra,” he says, referring to the al-Qaeda-linked Syrian rebels that recently cut ties with its parent organization. He adds that he’s not the only one suspicious of the Syrians. Being a hairdresser, he hears from a lot of locals.

“They say, ‘Let the police fucking remove them. Let them piss off all of them together! We don’t want anyone at all!’”

It didn’t used to be this way. Syrians have been living and working in Amchit for years. Before Syria's war, hundreds of thousands of them came to Lebanon to find work and send money home — Abdo among them.

“When the war started, we got scared and careful.”

On the day I arrive in the town, dozens of Syrians are lining the road, repaving the entire stretch throughout the town. Every construction site is manned by Syrians.

But the war has changed things, Sakkr says.

“I used to see them in front of my shop every day in the evening. You were able to find 40 or 50 people, and they stayed till 10 or 11 p.m. But when the war started, we got scared and careful.”

The unknown

Since the war began, the number of Syrians in the country has increased dramatically, transforming small towns like Amchit.

“There are too many,” says Marwan, a shopkeeper who serves dozens of Syrians every day. “In every area, the numbers of Syrians are multiplying. You used to see 1,000 and that’s not much, but now you see 2,000 or 3,000. There are strangers, new faces, new looks.”

“There’s always fear. Whenever there’s an explosion, it paralyzes the whole country,” he adds.

Marwan says there is a distance between the Syrians and the local Lebanese community, partly because they are from different backgrounds and religions.

“When Syrians come to my mini-market, my relationship with them is like my relationship with any customer of mine. You interact with them, you feel empathy towards them. But there are no visits, and no good communication between us,” he says.

“There’s still some fear of bonding with that person because of their situation in Syria. They have some sort of racial sectarianism. They say ‘We are Muslim, this one is Christian,’ and he stays away from you.”

Some people also point to history to explain their distrust. The Syrian Army occupied Lebanon throughout its 1975-1990 civil war, and beyond. It ruled the country with an iron fist, assassinating opponents and dominating political life until mass protests forced its withdrawal in 2005. The dreaded mukhabarat — secret police — were feared by rich and poor alike.

“We have felt like this since Syrians were [occupiers] in our country, and it’s not over yet,” Marwan says. “Even though we greet and kiss someone, we still feel fear and alertness.”

Life under curfew

Abdo first came to Lebanon 10 years ago, and until recently traveled back and forth. The war ended that. His wife and three young children came to live with him in Lebanon for a short while, but they were unable to obtain the necessary papers to stay. Now, Abdo sends money home.

He is a plumber by trade, but he takes any work he can get. Similar to migrant day laborers across the United States, Syrians in Amchit wake up early and wait in a square in the middle of town for construction site managers to drive through and pick up workers. He spends the daylight hours doing backbreaking work. When he finishes work at around 5 p.m., he rushes to buy food for dinner before the curfew takes effect at 7 p.m. (there are signs around town to remind him). Then, he and 30 others in his small building are inside for the evening, Abdo in a room not much bigger than a prison cell. He has a small television and a camping stove to cook with. The men pass the time drinking tea and watching movies.

“If we get caught by a police officer or someone in the street, they curse us and ask us why we are out. They ask us how many times they’ve told us about the curfew, ‘You should go buy your stuff before that,’” says Abdo.

“This is our life here. I’ve been here on and off for a long time. I know the Lebanese regulations as I know my kids and my house.”

Abdo says the atmosphere now for Syrians like him is so bad that he would return home if he could.

“But I cannot do it before I improve my situation. Winter is near, so life becomes harder, you need a heating stove, fuel, a heater and wood.”

As I leave the village, I pass Abdo standing nervously on the road close to the door of his home. He is too afraid to wait in the main square any more, and so today he did not work.

Richard Hall reported from Amchit, Lebanon.