The Maker Movement that was born in the USA has taken on Chinese characteristics

Are you a maker? Probably so, even if you haven’t heard the term.

“We were born makers, and if we choose to develop our interest in making, anybody can do this,” says Dale Dougherty, who founded the Maker Movement 11 years ago in the San Francisco Bay Area. “It’s not like a few geeks, a few people, are wired to do this. We’re all wired to do this.”

Dougherty’s original idea then was to encourage people in a country that had outsourced so many manufacturing jobs, to reconnect with the creativity that comes from making things with your hands — gadgets, robots, 3-D printing projects, but also crafts, cooking, even gardening. That, after all, is the way a lot of great inventors got started – but there’s no pressure here.

“It’s not about how good you are. It’s about the sense of control and the sense of purpose and of setting your own direction, doing things that are meaningful to you.”

So, first came MakerSpaces — kind of like communal use work benches or shop, with tools and materials and space for makers of all sorts to gather and share ideas. It started small, and went big — went global.

There are now thousands of MakerSpaces in dozens of countries around the world. There’s Make Magazine, online Maker communities. There are some 180 annual Maker Faires — annual gatherings of Makers. More than 1.2 million people went to a Maker Faire last year alone in places like France, Italy, Turkey, Egpyt and China. And there's been international cross-pollination among Makers. Tuna Tumer, 14, from Ankara, Turkey traveled to California with his dad for this year's SIlicon Valley Maker Faire, to learn from other makers and to show off his latest invention, a business card-sized metal card with scalloped edges, that can measure the radius of corners.

"This is a problem that most designers face, because there isn’t a tool for it," he says. "So for the radius of what they put on their designs, they just put a random number, but this is a really easy tool to use, so you just use it and write it down." All this for $5 at the Maker Faire. Tumer said he's considered himself a maker "ever since I got a 3D printer a couple of years ago … now, when I'm bored, I just experiment with making things with it." He now has his own company, TNA Designs. Tumer says the real value to him of being at the Maker Faire was meeting other makers, and seeing what they're doing.

"It's really cool to meet new people, the whole society of makers, and get new ideas," he says. "It's a really cool place."

At first, you might think — China? China’s been the factory of the world for decades. Why does China need a Maker Movement? Well, if the US embrace of the Maker Movement was to reconnect with a kind of creativity lost when the US moved from manufacturing to services and the knowledge economy, Chinese who have long been finding clever ways to recombine components want both to raise their innovation game and to get some recognition for the skill and creativity that already goes into manufacturing in China.

In its early years in the US, the Maker Movement was meant to help Americans see themselves not just as consumers, but as producers.

“And I started shaping the Maker Faire around this,” Dougherty says.

“My way of doing that was to show them lots of their fellow citizens doing this. They were just ordinary people, their neighbors. And it gets you thinking, ‘well I could do that.’ It didn't have to be, ‘oh, they're just wonderful entrepreneurs, they're off doing their crazy things.’ It harkens back to the world of hobbies, which I feel are important and sometimes slighted in our culture as, ‘well, it’s a hobby. It's something he does in his spare time.’ But people really value that time, because it's theirs and it replenishes them for other work. And often it, in funny ways, it influences even what they might do it more seriously for work as well.

That was why, from the beginning, the Maker Movement was about play, not work, Dougherty says. It may sound self-indulgent, but he believes a mind at play is a mind open to innovating.

“I actually think it comes, not from sitting down and thinking that you're going to innovate and create something,” he says. “I think it comes from these moments of play, when you're trying things, and you're immersed in a problem set that you suddenly find compelling, and you want to figure your way out of it. And you see something that you would have never seen if you just stood on outside and watch someone else do it. And so I think innovators, in a sense, become that way because they are comfortable playing.”

That hasn’t been the approach thus far, in trying to increase innovation in China.

China’s leaders have had a goal for almost two decades now, to make China a global power, ideally a global leader, in innovation. They’ve invested hundreds of billions of dollars in science parks, research labs, and other initiatives. They’ve incentivized researchers to come up with patents and journal articles — and they have. But so far, they’ve done better on quantity than on quality. It’s not that the potential isn’t there — it’s that, in many cases, the environment doesn’t support thinking that challenges the established way of doing things, or of open-ended research, failing, and trying again, and failing again, maybe for years, before hitting that eureka moment.

The private sector is more nimble, but also cut-throat competitive, and often looking for the fastest way to a profit, which is usually to copy and recombine, rather than play around and come up with something startlingly new.

Into this environment in China comes the Maker Movement. It started about five years ago, when a Taiwanese former PhD student-turned startup entrepreneur, David Li, moved from California to Shanghai — and set up China’s first MakerSpace. Another MakerSpace opened up in Shenzhen, just opposite Hong Kong, and now there are hundreds in China.

China’s leaders have embraced the Maker Movement, offering welcome resources and publicity, but also a less welcome reflexive desire to take MakerSpaces, which are meant to be open and inviting, without too many rules and expectations, and add structure and, well, expectations.

And this is happening at a time when China’s tech-savvy, relatively worldly, younger generation has, under Xi Jinping’s rule, seen open spaces for creative expression and challenges to Communist Party-approved ways of thinking close up, online, in classrooms and in the media. More websites have been blocked online, more Western textbooks banned. Innovation is still possible, in such an environment; there’s just a higher degree of difficulty to achieve it, given that China’s would-be innovators don’t have access to the same ideas, debates and habits of critical and creative thinking that their counterparts in other countries might have.

But there’s an old saying in China — "the sky is high, and the emperor is far away." And the city of Shenzhen is 1,300 miles away from the halls of power in Beijing. In every sense. It’s looser, less political. A fishing village-turned city of some 22 million mostly migrants, Shenzen is a longtime center for manufacturing and now the darling of Silicon Valley entrepreneurs, who see Shenzhen's agility with hardware to be a perfect complement to the Silicon Valley software and ideas factory.

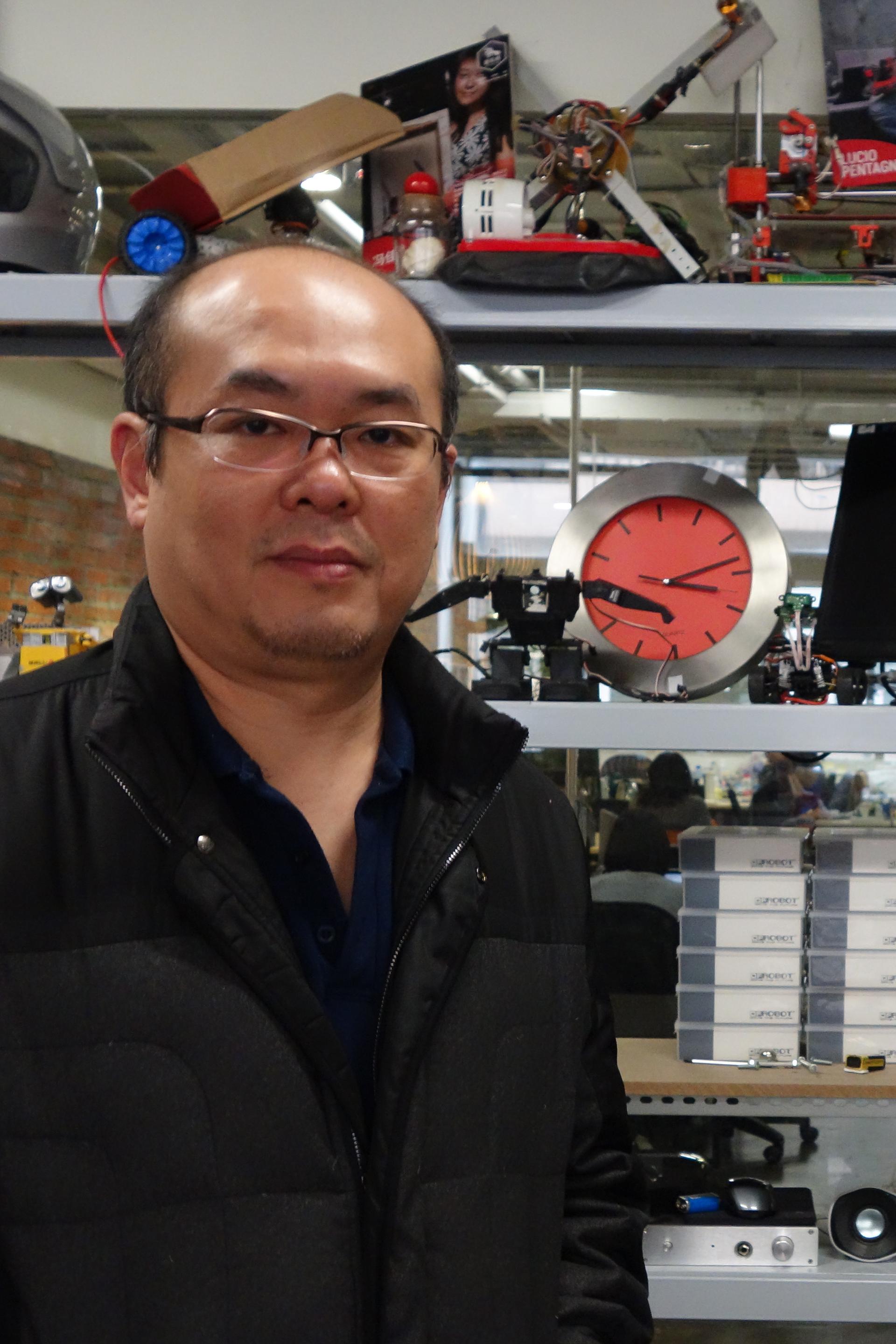

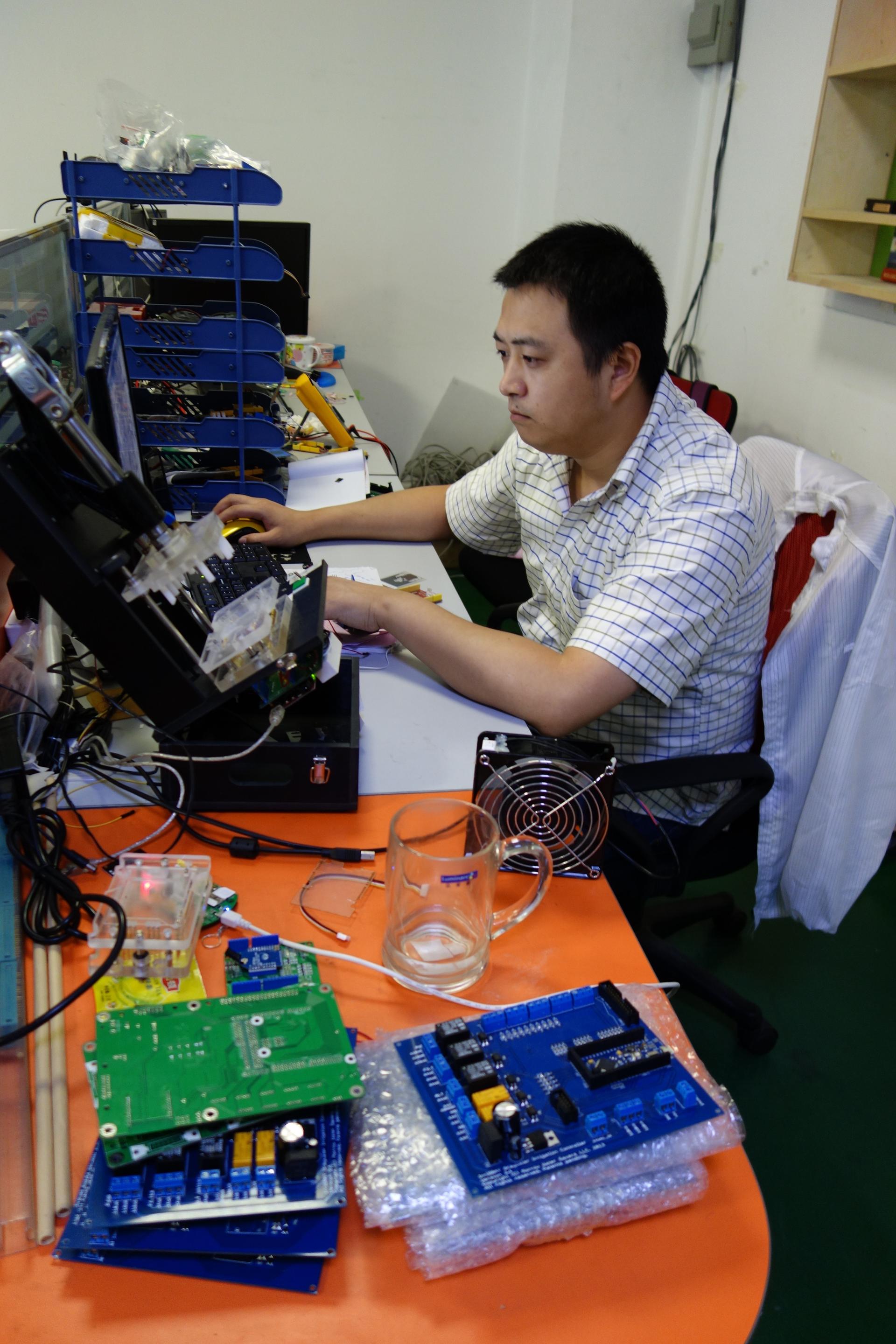

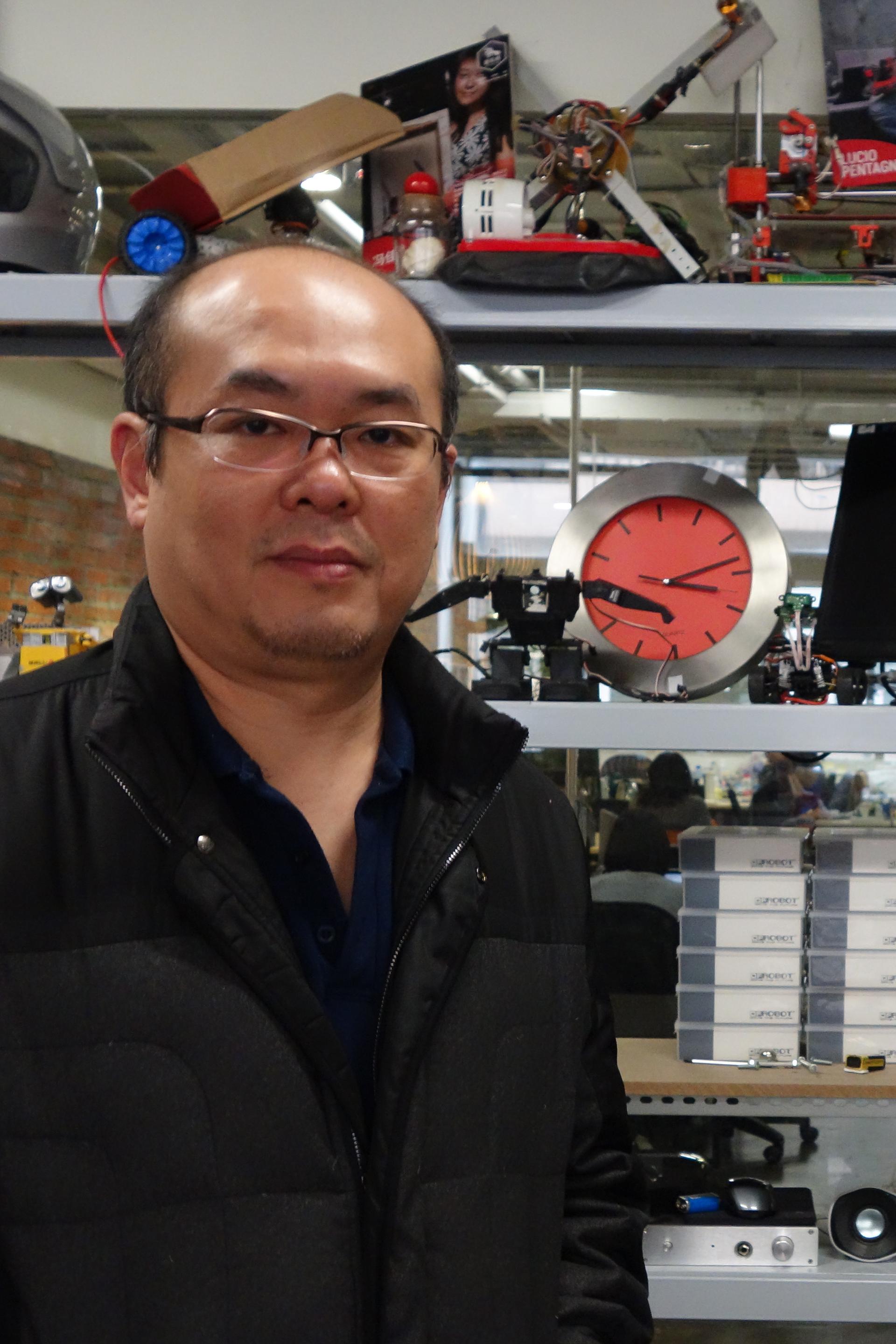

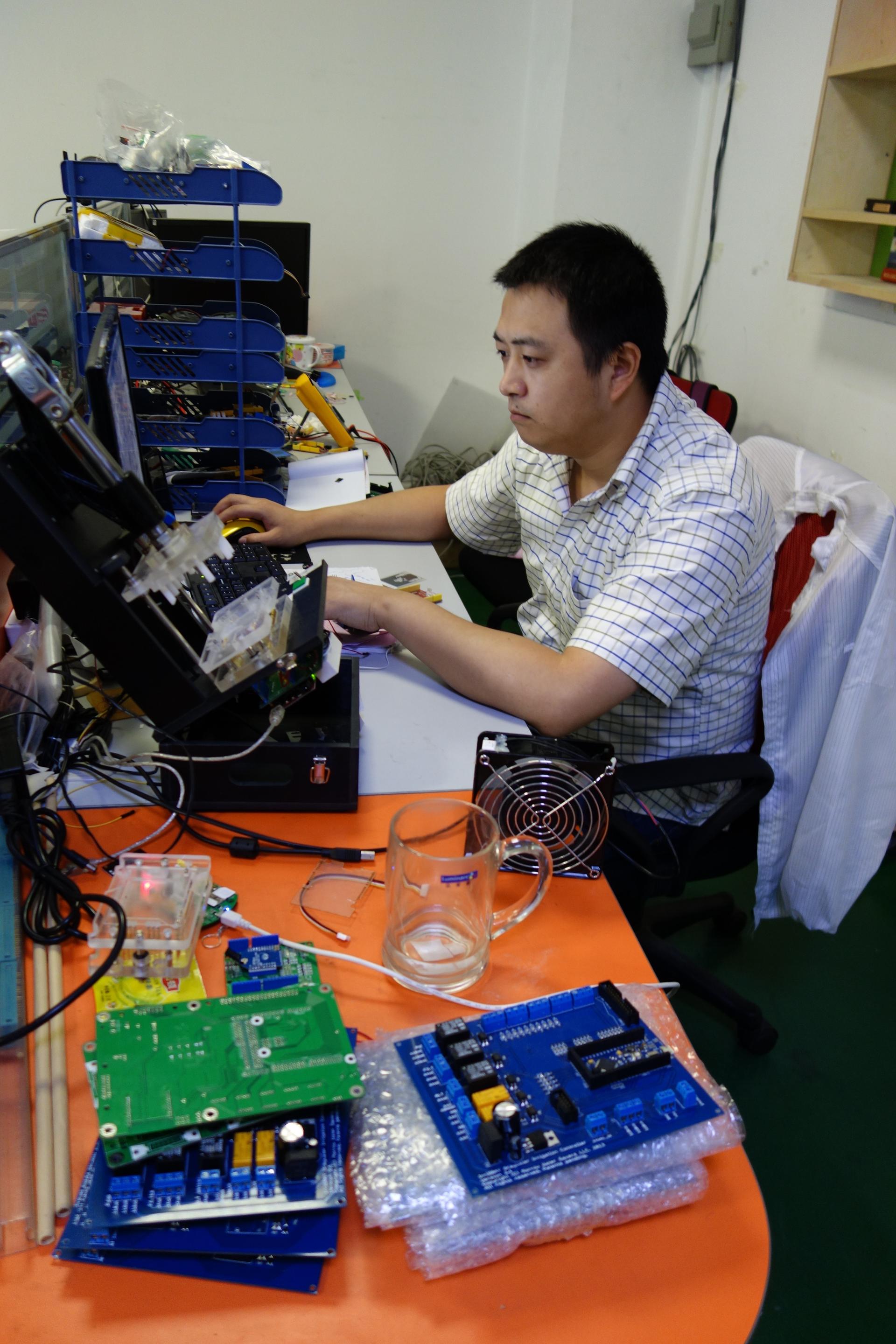

An influential player in having helped make that happen is Eric Pan, a native of Sichuan province, a former engineering student who, as a kid, loved to take things apart and put them back together. He is a former Intel employee who came to Shenzhen to start his own company, SEEED studio. (That’s not a typo; it’s spelled with three ‘e’s.) It sells open-source hardware products to Makers and others, and also provides manufacturing services to companies. Pan also opened Shenzhen’s first MakerSpace.

“It started off very humble,” Pan says. “I was trying to help Makers out, because that’s really fun. And I just needed to make myself survive. Then, it went really well. It exceeded my expectations.”

Premier Li Keqiang came to see Pan’s MakerSpace in early 2015 and then, as so often happens when the Chinese government decides something is worth doing, it went big, at speed. Some officials seemed to see MakerSpaces as little more than incubators, that would become accelerators, and then start-ups that would contribute to economic growth and innovation. China’s early makers, including Pan and Li, have gently pushed back.

“We are trying very hard to distinguish between MakerSpaces and incubators,” Pan says. “With MakerSpaces, we’re talking about passions, about exploring what you want to do, where you can explore all the possibilities to try new things.

But the gravity of the Chinese government’s will is strong, and China’s version of the Maker Movement got pulled a little closer to its orbit during the Shenzhen Maker Faire last year, which Eric Pan spearheaded.

It was huge. About 200,000 people came, and it covered several city blocks — a far cry from a few enthusiasts gathering in a room four years earlier. There was a whole Shenzhen Maker Week, with events all over town. But at the opening ceremony, where Communist Party officials spoke, it was walled off, with just state-run media, and a few invited guests.

Lots of control. Very Communist Party.

There was even government resistance to letting Dale Dougherty speak, but Eric Pan ceded some of his time on the stage to this man he clearly respects. After that, Dale had some time to wander around, and see how the Maker Movement was taking off in Shenzhen, and he found some interesting contrasts with the American Maker Movement.

“My experience at the Shenzhen Maker Faire, I'd go down a row of exhibits and they were all drones. And they all look the same. And I'd ask them, ‘what does your drone do?’ And they said, ‘well, it's my drone. I made it.’ I said, ‘Well, great. How is it different than his drone?’ ‘Well it's not. It's a drone, you know? And I can make it.’ Someone said to me the Chinese are really good at anything from one to a million, but it's zero to one they have a problem with. And in some ways, it's that real thing that, like, something's missing. ‘I'm going to create something that doesn't exist.’ That's where innovation is really about when you see that opportunity and you trust and you take the risk to do that."

There is plenty of entrepreneurial spirit in China, plenty of people who were willing to take risks. What’s in shorter supply is breakthrough, game-changing innovation that had as great an impact outside China’s borders as inside.

One reason, perhaps, is that so much creative energy in China goes to getting around government-imposed obstacles and restrictions, or to finding out that someone’s come up with a catchy idea — the hoverboard, for instance — and getting to market before the inventor can.

Can the same energy go to solving the world’s problems, in tech, biotech and beyond? It could — or at least it might, with the right incentives, the right supporting environment. The Maker Movement might help. The way the government is engaging with the Maker Movement, may or may not.

Meanwhile, President Barack Obama has been celebrating the Maker Movement, with a White House Maker Faire, some funding, and words of appreciation — but without anything like the same degree of hands-on effort to control the outcome. He has said that the Maker Movement, along with the emerging Internet of Things, could end up having as great an impact as the rise of the internet 25 years ago.

“I get asked all the time, ‘is Shenzhen really creative?,” she says. One of the Europeans visitors here said, ‘well, they’re not really creative, here, because they’re focused on business. They’re focused on products.’ So there’s this interesting tension here between, and I’m simplifying right now, this Western view of, ‘oh, you shouldn’t be talking about money up front, you should be unleashing your passion, and that’s true creativity. I would say it’s more interesting to say, ‘well, what are the roots of production here, the history of production here, and what could creativity mean here on its own terms, rather than using familiar frames of reference, like Silicon Valley-type notions of creativity and innovation, that you hear very often thrown around here at the Maker Faire.”

And yet, Chinese innovations are not yet having the kind of impact globally as the Chinese government set out to make happen, when they set goals back in 1998 and started pouring hundreds of billions of dollars into science parks and research centers, recruiting top overseas Chinese and foreign talent as well as using impressive talent at home.

This begs a question. How necessary is it, really, for China, or India, or any other emerging economic power, to hit the highest rung of the innovation ladder, to come out with the kinds of innovations that change lives and how people live, around the globe? Throughout human history, relatively few countries have hit that mark. But China happens to be one of them. For a thousand years or so, up until about a thousand years ago, China was one of the most innovative places on earth, and Chinese astronomy was among the most advanced at that time. And then, the political environment changed. Incentives changed. There was less social support, or encouragement or recognition for coming up with — shaking up established ways of doing things, and proposing something radically new.

And now, the Chinese government wants to launch a new era in which China is a global player, perhaps a global leader, in innovation — but it wants to do it by allowing innovation and critical thinking in specific silos — tech, biotech, hard sciences — but not in creative fields, or academia, where the same kind of thinking could challenge the Communist Party in ways it finds deeply uncomfortable.

Shenzhen seems to have found a sweet spot, transforming three decades of experience in manufacturing into a draw for Silicon Valley innovators who need partners to bring form to their ideas, and to do it with speed, with an impressively efficient supply chain, and with a certain innovative flair that the Maker Movement now celebrates. But how much are Chinese in Shenzhen, or anywhere in China, coming up with innovation at the highest level?

“I think the absolute percentage is very, very low,” says Eric Pan of SEEED studio. “Because Shenzhen has gotten used to ‘Copy to China.’ In the beginning, we manufactured something, like Nokia, and we imitated the design. But I think from all these imitations, people have difficulty differentiating from one to another. Some of the weaker teams, they need to do differently. They can’t just differentiate on cost only. They need to come up with some new functionality or design. That’s where I think innovation comes from."

“It’s like, if you want to write a book, you first need to learn the alphabet, and repeat, repeat, repeat. And then you come up with words. Then you can form your own sentences, and express your experience. In Shenzhen, people know how to write a sentence now. The next stage is to express themselves differently.”

For more on the Maker Movement:

Why the Maker Movement Matters: Part 1, the Tools Revolution

MAKING IT: Pick up a spot welder and join the revolution.

MAKER MOVEMENT REINVENTS EDUCATION

For other takes on innovation in China:

Clay Shirky on tech and the internet in China

Smart money pouring into Shenzhen as city becomes hotbed of innovation

Are you a maker? Probably so, even if you haven’t heard the term.

“We were born makers, and if we choose to develop our interest in making, anybody can do this,” says Dale Dougherty, who founded the Maker Movement 11 years ago in the San Francisco Bay Area. “It’s not like a few geeks, a few people, are wired to do this. We’re all wired to do this.”

Dougherty’s original idea then was to encourage people in a country that had outsourced so many manufacturing jobs, to reconnect with the creativity that comes from making things with your hands — gadgets, robots, 3-D printing projects, but also crafts, cooking, even gardening. That, after all, is the way a lot of great inventors got started – but there’s no pressure here.

“It’s not about how good you are. It’s about the sense of control and the sense of purpose and of setting your own direction, doing things that are meaningful to you.”

So, first came MakerSpaces — kind of like communal use work benches or shop, with tools and materials and space for makers of all sorts to gather and share ideas. It started small, and went big — went global.

There are now thousands of MakerSpaces in dozens of countries around the world. There’s Make Magazine, online Maker communities. There are some 180 annual Maker Faires — annual gatherings of Makers. More than 1.2 million people went to a Maker Faire last year alone in places like France, Italy, Turkey, Egpyt and China. And there's been international cross-pollination among Makers. Tuna Tumer, 14, from Ankara, Turkey traveled to California with his dad for this year's SIlicon Valley Maker Faire, to learn from other makers and to show off his latest invention, a business card-sized metal card with scalloped edges, that can measure the radius of corners.

"This is a problem that most designers face, because there isn’t a tool for it," he says. "So for the radius of what they put on their designs, they just put a random number, but this is a really easy tool to use, so you just use it and write it down." All this for $5 at the Maker Faire. Tumer said he's considered himself a maker "ever since I got a 3D printer a couple of years ago … now, when I'm bored, I just experiment with making things with it." He now has his own company, TNA Designs. Tumer says the real value to him of being at the Maker Faire was meeting other makers, and seeing what they're doing.

"It's really cool to meet new people, the whole society of makers, and get new ideas," he says. "It's a really cool place."

At first, you might think — China? China’s been the factory of the world for decades. Why does China need a Maker Movement? Well, if the US embrace of the Maker Movement was to reconnect with a kind of creativity lost when the US moved from manufacturing to services and the knowledge economy, Chinese who have long been finding clever ways to recombine components want both to raise their innovation game and to get some recognition for the skill and creativity that already goes into manufacturing in China.

In its early years in the US, the Maker Movement was meant to help Americans see themselves not just as consumers, but as producers.

“And I started shaping the Maker Faire around this,” Dougherty says.

“My way of doing that was to show them lots of their fellow citizens doing this. They were just ordinary people, their neighbors. And it gets you thinking, ‘well I could do that.’ It didn't have to be, ‘oh, they're just wonderful entrepreneurs, they're off doing their crazy things.’ It harkens back to the world of hobbies, which I feel are important and sometimes slighted in our culture as, ‘well, it’s a hobby. It's something he does in his spare time.’ But people really value that time, because it's theirs and it replenishes them for other work. And often it, in funny ways, it influences even what they might do it more seriously for work as well.

That was why, from the beginning, the Maker Movement was about play, not work, Dougherty says. It may sound self-indulgent, but he believes a mind at play is a mind open to innovating.

“I actually think it comes, not from sitting down and thinking that you're going to innovate and create something,” he says. “I think it comes from these moments of play, when you're trying things, and you're immersed in a problem set that you suddenly find compelling, and you want to figure your way out of it. And you see something that you would have never seen if you just stood on outside and watch someone else do it. And so I think innovators, in a sense, become that way because they are comfortable playing.”

That hasn’t been the approach thus far, in trying to increase innovation in China.

China’s leaders have had a goal for almost two decades now, to make China a global power, ideally a global leader, in innovation. They’ve invested hundreds of billions of dollars in science parks, research labs, and other initiatives. They’ve incentivized researchers to come up with patents and journal articles — and they have. But so far, they’ve done better on quantity than on quality. It’s not that the potential isn’t there — it’s that, in many cases, the environment doesn’t support thinking that challenges the established way of doing things, or of open-ended research, failing, and trying again, and failing again, maybe for years, before hitting that eureka moment.

The private sector is more nimble, but also cut-throat competitive, and often looking for the fastest way to a profit, which is usually to copy and recombine, rather than play around and come up with something startlingly new.

Into this environment in China comes the Maker Movement. It started about five years ago, when a Taiwanese former PhD student-turned startup entrepreneur, David Li, moved from California to Shanghai — and set up China’s first MakerSpace. Another MakerSpace opened up in Shenzhen, just opposite Hong Kong, and now there are hundreds in China.

China’s leaders have embraced the Maker Movement, offering welcome resources and publicity, but also a less welcome reflexive desire to take MakerSpaces, which are meant to be open and inviting, without too many rules and expectations, and add structure and, well, expectations.

And this is happening at a time when China’s tech-savvy, relatively worldly, younger generation has, under Xi Jinping’s rule, seen open spaces for creative expression and challenges to Communist Party-approved ways of thinking close up, online, in classrooms and in the media. More websites have been blocked online, more Western textbooks banned. Innovation is still possible, in such an environment; there’s just a higher degree of difficulty to achieve it, given that China’s would-be innovators don’t have access to the same ideas, debates and habits of critical and creative thinking that their counterparts in other countries might have.

But there’s an old saying in China — "the sky is high, and the emperor is far away." And the city of Shenzhen is 1,300 miles away from the halls of power in Beijing. In every sense. It’s looser, less political. A fishing village-turned city of some 22 million mostly migrants, Shenzen is a longtime center for manufacturing and now the darling of Silicon Valley entrepreneurs, who see Shenzhen's agility with hardware to be a perfect complement to the Silicon Valley software and ideas factory.

An influential player in having helped make that happen is Eric Pan, a native of Sichuan province, a former engineering student who, as a kid, loved to take things apart and put them back together. He is a former Intel employee who came to Shenzhen to start his own company, SEEED studio. (That’s not a typo; it’s spelled with three ‘e’s.) It sells open-source hardware products to Makers and others, and also provides manufacturing services to companies. Pan also opened Shenzhen’s first MakerSpace.

“It started off very humble,” Pan says. “I was trying to help Makers out, because that’s really fun. And I just needed to make myself survive. Then, it went really well. It exceeded my expectations.”

Premier Li Keqiang came to see Pan’s MakerSpace in early 2015 and then, as so often happens when the Chinese government decides something is worth doing, it went big, at speed. Some officials seemed to see MakerSpaces as little more than incubators, that would become accelerators, and then start-ups that would contribute to economic growth and innovation. China’s early makers, including Pan and Li, have gently pushed back.

“We are trying very hard to distinguish between MakerSpaces and incubators,” Pan says. “With MakerSpaces, we’re talking about passions, about exploring what you want to do, where you can explore all the possibilities to try new things.

But the gravity of the Chinese government’s will is strong, and China’s version of the Maker Movement got pulled a little closer to its orbit during the Shenzhen Maker Faire last year, which Eric Pan spearheaded.

It was huge. About 200,000 people came, and it covered several city blocks — a far cry from a few enthusiasts gathering in a room four years earlier. There was a whole Shenzhen Maker Week, with events all over town. But at the opening ceremony, where Communist Party officials spoke, it was walled off, with just state-run media, and a few invited guests.

Lots of control. Very Communist Party.

There was even government resistance to letting Dale Dougherty speak, but Eric Pan ceded some of his time on the stage to this man he clearly respects. After that, Dale had some time to wander around, and see how the Maker Movement was taking off in Shenzhen, and he found some interesting contrasts with the American Maker Movement.

“My experience at the Shenzhen Maker Faire, I'd go down a row of exhibits and they were all drones. And they all look the same. And I'd ask them, ‘what does your drone do?’ And they said, ‘well, it's my drone. I made it.’ I said, ‘Well, great. How is it different than his drone?’ ‘Well it's not. It's a drone, you know? And I can make it.’ Someone said to me the Chinese are really good at anything from one to a million, but it's zero to one they have a problem with. And in some ways, it's that real thing that, like, something's missing. ‘I'm going to create something that doesn't exist.’ That's where innovation is really about when you see that opportunity and you trust and you take the risk to do that."

There is plenty of entrepreneurial spirit in China, plenty of people who were willing to take risks. What’s in shorter supply is breakthrough, game-changing innovation that had as great an impact outside China’s borders as inside.

One reason, perhaps, is that so much creative energy in China goes to getting around government-imposed obstacles and restrictions, or to finding out that someone’s come up with a catchy idea — the hoverboard, for instance — and getting to market before the inventor can.

Can the same energy go to solving the world’s problems, in tech, biotech and beyond? It could — or at least it might, with the right incentives, the right supporting environment. The Maker Movement might help. The way the government is engaging with the Maker Movement, may or may not.

Meanwhile, President Barack Obama has been celebrating the Maker Movement, with a White House Maker Faire, some funding, and words of appreciation — but without anything like the same degree of hands-on effort to control the outcome. He has said that the Maker Movement, along with the emerging Internet of Things, could end up having as great an impact as the rise of the internet 25 years ago.

“I get asked all the time, ‘is Shenzhen really creative?,” she says. One of the Europeans visitors here said, ‘well, they’re not really creative, here, because they’re focused on business. They’re focused on products.’ So there’s this interesting tension here between, and I’m simplifying right now, this Western view of, ‘oh, you shouldn’t be talking about money up front, you should be unleashing your passion, and that’s true creativity. I would say it’s more interesting to say, ‘well, what are the roots of production here, the history of production here, and what could creativity mean here on its own terms, rather than using familiar frames of reference, like Silicon Valley-type notions of creativity and innovation, that you hear very often thrown around here at the Maker Faire.”

And yet, Chinese innovations are not yet having the kind of impact globally as the Chinese government set out to make happen, when they set goals back in 1998 and started pouring hundreds of billions of dollars into science parks and research centers, recruiting top overseas Chinese and foreign talent as well as using impressive talent at home.

This begs a question. How necessary is it, really, for China, or India, or any other emerging economic power, to hit the highest rung of the innovation ladder, to come out with the kinds of innovations that change lives and how people live, around the globe? Throughout human history, relatively few countries have hit that mark. But China happens to be one of them. For a thousand years or so, up until about a thousand years ago, China was one of the most innovative places on earth, and Chinese astronomy was among the most advanced at that time. And then, the political environment changed. Incentives changed. There was less social support, or encouragement or recognition for coming up with — shaking up established ways of doing things, and proposing something radically new.

And now, the Chinese government wants to launch a new era in which China is a global player, perhaps a global leader, in innovation — but it wants to do it by allowing innovation and critical thinking in specific silos — tech, biotech, hard sciences — but not in creative fields, or academia, where the same kind of thinking could challenge the Communist Party in ways it finds deeply uncomfortable.

Shenzhen seems to have found a sweet spot, transforming three decades of experience in manufacturing into a draw for Silicon Valley innovators who need partners to bring form to their ideas, and to do it with speed, with an impressively efficient supply chain, and with a certain innovative flair that the Maker Movement now celebrates. But how much are Chinese in Shenzhen, or anywhere in China, coming up with innovation at the highest level?

“I think the absolute percentage is very, very low,” says Eric Pan of SEEED studio. “Because Shenzhen has gotten used to ‘Copy to China.’ In the beginning, we manufactured something, like Nokia, and we imitated the design. But I think from all these imitations, people have difficulty differentiating from one to another. Some of the weaker teams, they need to do differently. They can’t just differentiate on cost only. They need to come up with some new functionality or design. That’s where I think innovation comes from."

“It’s like, if you want to write a book, you first need to learn the alphabet, and repeat, repeat, repeat. And then you come up with words. Then you can form your own sentences, and express your experience. In Shenzhen, people know how to write a sentence now. The next stage is to express themselves differently.”

For more on the Maker Movement:

Why the Maker Movement Matters: Part 1, the Tools Revolution

MAKING IT: Pick up a spot welder and join the revolution.

MAKER MOVEMENT REINVENTS EDUCATION

For other takes on innovation in China:

Clay Shirky on tech and the internet in China

Smart money pouring into Shenzhen as city becomes hotbed of innovation