What does Brexit mean for the Paris climate agreement?

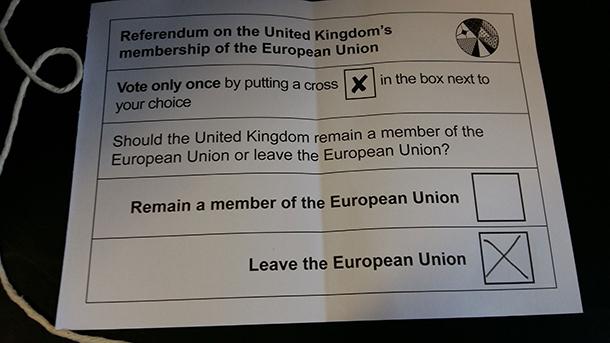

The “Leave” campaign, which won 51.9% of the British vote, could have far-reaching effects in all areas of life in the UK, including the environment

The UK’s vote to leave the European Union has raised questions about how Europe will meet its commitments to mitigate the effects of climate change under the Paris climate agreement.

The EU negotiated its greenhouse gas emissions cuts as a bloc, so there are concerns that Brexit could slow ratification of the Paris Climate Agreement. That accord can go into force if 50 countries, and those representing 50 percent of global emissions, ratify it. The EU, including the UK, represents only 10 percent of emissions, but it has been a global leader on the issue.

So, what might the UK’s absence do to the agreement?

“At best, this is a distraction. At worst, this is disruptive,” says Rachel Kyte, the CEO of the UN’s Sustainable Energy for All initiative. “At this point, absent Brexit, we would be looking at ramping up action to make the European economy as productive and competitive as possible. We would be looking for perhaps even greater ambition, because, remember, in Paris, we agreed to [a target of] way below 2 degrees Celsius. The INDCs (Intended Nationally Determined Contributions) that were filed in Paris, when you add them up, got to just about three degrees, so we have more work to do anyway.”

Until Brexit, the assumption was that the European Union would ratify the Paris Agreement quickly, Kyte says. But for the EU to ratify, every EU member must ratify within its own government — France and Hungary, for example, have already done that. So, Kyte says, the UK would appear to have two options. One: it can ratify now as an EU member state, which would enable EU-wide ratification to go ahead, or two: postpone ratification. In this case, the EU would be unable to ratify as a bloc for as long as the Brexit negotiations persist, which risks a potential delay in the Paris Agreement’s entry into force.

For now, the European Union is continuing on as if nothing has changed, because Article 50, which begins the process of withdrawal, has not yet been invoked. The concern within the EU is over the uncertainty of knowing when and how the United Kingdom will exit the European Union and exactly under what terms, and what decisions the European Union and the UK will reach as far as the UK going it alone or continuing to operate within the EU's targets.

The targets for emissions reductions — a 40 percent economy-wide reduction over 1990 emissions levels — took into account emissions generated by the UK’s economy, Kyte points out. This kind of regional energy integration has increasingly been the focus of developing low-carbon economies throughout the world, so Britain's energy future lies within a European energy market.

“Our ability to import clean wind power from Denmark, for example, at a reasonable price is part of the future that we were building,” Kyte says. “So I think there are question marks about what the commitment of the country, and the new government, is to that kind of future.”

Kyle believes that until now, the UK has been a “powerful force for good within the European union” and its absence could have a negative effect on global progress toward addressing climate issues.

“When it comes to energy, climate and sustainable development, the UK has been a steady voice for action, because we've had a cross-party commitment to greening the economy and to climate action over the past decade or more,” Kyte says. “It's been a constant leadership voice within the European Union. To lose that voice, I think, is to the detriment of the European Union.”

This article is based on an interview that aired on PRI’s Living on Earth with Steve Curwood.

The UK’s vote to leave the European Union has raised questions about how Europe will meet its commitments to mitigate the effects of climate change under the Paris climate agreement.

The EU negotiated its greenhouse gas emissions cuts as a bloc, so there are concerns that Brexit could slow ratification of the Paris Climate Agreement. That accord can go into force if 50 countries, and those representing 50 percent of global emissions, ratify it. The EU, including the UK, represents only 10 percent of emissions, but it has been a global leader on the issue.

So, what might the UK’s absence do to the agreement?

“At best, this is a distraction. At worst, this is disruptive,” says Rachel Kyte, the CEO of the UN’s Sustainable Energy for All initiative. “At this point, absent Brexit, we would be looking at ramping up action to make the European economy as productive and competitive as possible. We would be looking for perhaps even greater ambition, because, remember, in Paris, we agreed to [a target of] way below 2 degrees Celsius. The INDCs (Intended Nationally Determined Contributions) that were filed in Paris, when you add them up, got to just about three degrees, so we have more work to do anyway.”

Until Brexit, the assumption was that the European Union would ratify the Paris Agreement quickly, Kyte says. But for the EU to ratify, every EU member must ratify within its own government — France and Hungary, for example, have already done that. So, Kyte says, the UK would appear to have two options. One: it can ratify now as an EU member state, which would enable EU-wide ratification to go ahead, or two: postpone ratification. In this case, the EU would be unable to ratify as a bloc for as long as the Brexit negotiations persist, which risks a potential delay in the Paris Agreement’s entry into force.

For now, the European Union is continuing on as if nothing has changed, because Article 50, which begins the process of withdrawal, has not yet been invoked. The concern within the EU is over the uncertainty of knowing when and how the United Kingdom will exit the European Union and exactly under what terms, and what decisions the European Union and the UK will reach as far as the UK going it alone or continuing to operate within the EU's targets.

The targets for emissions reductions — a 40 percent economy-wide reduction over 1990 emissions levels — took into account emissions generated by the UK’s economy, Kyte points out. This kind of regional energy integration has increasingly been the focus of developing low-carbon economies throughout the world, so Britain's energy future lies within a European energy market.

“Our ability to import clean wind power from Denmark, for example, at a reasonable price is part of the future that we were building,” Kyte says. “So I think there are question marks about what the commitment of the country, and the new government, is to that kind of future.”

Kyle believes that until now, the UK has been a “powerful force for good within the European union” and its absence could have a negative effect on global progress toward addressing climate issues.

“When it comes to energy, climate and sustainable development, the UK has been a steady voice for action, because we've had a cross-party commitment to greening the economy and to climate action over the past decade or more,” Kyte says. “It's been a constant leadership voice within the European Union. To lose that voice, I think, is to the detriment of the European Union.”

This article is based on an interview that aired on PRI’s Living on Earth with Steve Curwood.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!