Syria: Pledge to review emergency law unlikely to quell protests

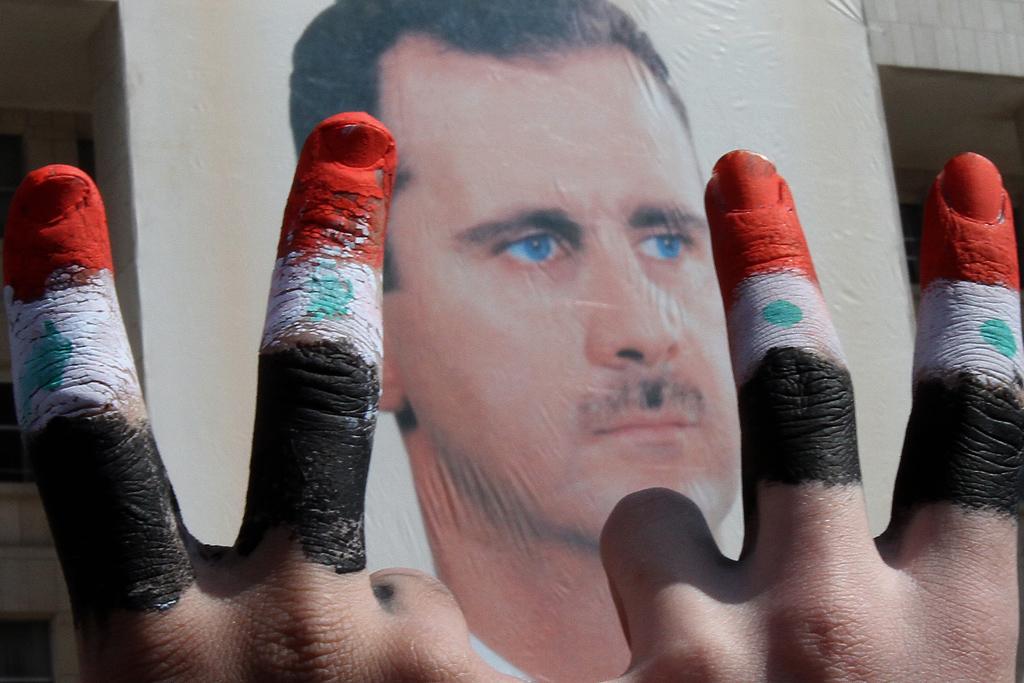

Two men with the fingers painted in the colors of the Syrian flag show the victory “V” sign in front of a poster of President Bashar al-Assad during a rally in central Damascus on March 29, 2011.

DAMASCUS, Syria — Syria's President Bashar al-Assad announced today the formation of a committee to review the country's long-standing emergency laws, an apparent move to quell the largest demonstrations the country has seen in half a century.

But for the protesters, who have heard such promises before, the pledge might have been too little too late.

Since the start of protests in the southern city of Deraa on March 18, international rights groups said more than 60 protesters have been killed by Syrian security forces, many of whom fired on unarmed crowds. Local activists said that number is closer to 100 and put the number of those arrested in a massive crackdown against journalists, lawyers, activists and bloggers at about 500.

The emergency laws — which have been in effect for nearly five decades of one-party rule, most of which has been under the Assad family — are a key grievance for Syrians demanding greater freedoms in the wake of the revolutions in Tunisia and Egypt.

The Syrian protests began when a group of angry locals in Deraa began to demand the release of several teenagers who had been jailed for scrawling anti-government graffiti on a city wall.

Like the estimated 3,000 to 4,000 other political prisoners held in Syria, the boys were detained under Syria’s emergency laws, which suspend many aspects of the constitution and allow sweeping powers of arrest on catch-all charges such as “weakening national sentiment” and “opposing the goals of the revolution.”

Assad was expected to address those laws, the bedrock of the security state, in a much-anticipated speech Wednesday, his first televised address before Parliament since the unrest began.

But Assad's speech made only passing reference to the controversial laws. Instead, the president pointed nearly a dozen times to the “conspiracy,” “plots” and “sabotage” targeting Syria from outside.

“The objective was to fragment Syria, to bring down Syria as a nation to enforce an Israeli agenda,” Assad said in his speech, during which

he was interrupted several times by members of the Baath-controlled parliament pledging their support for the regime.

Earlier in the week, Assad sacked his cabinet, blaming them for the slow pace of reform despite the fact that Syria’s laws are issued not by the largely rubber stamp parliament or cabinet, but by presidential decree.

Assad acknowledged in his speech that "Syrian people have demands that have not been met," but failed to address those demands explicitly — which left many baffled.

“Thousands of people contacted me — top officials, deputy ministers, sons of ambassadors — saying, ‘You should expect big reform, you will be amazed’,” said Ayman Abdel Nour, a former Baath Party reformer and childhood friend of the president’s, now editor-in-chief of the All4Syria news agency. “After the speech they were all shocked. No one dared write anything back to me.”

The confusion continued today when the country's state news agency announced that a "committee" would be formed to review the emergency laws.

The committee will prepare “legislation including protecting the nation's security and the citizen's dignity and fighting terrorism, paving the way for lifting the emergency law,” the news agency reported. It added that the review would be complete by the last week of April.

A similar pledge to review the emergency laws, as well as to open Syria to multi-party politics, had been made before — at the 2005 Baath Party conference — yet nothing ever materialized.

For those Syrians who say they are suffocating under the laws, the speech only added to their desire for a change in leadership.

“We have lived under a dictatorship regime for four decades and now it is time to get rid of this regime,” said an opposition figure in Damascus. “He gave us nothing. He should release all political prisoners immediately and stop the security apparatus from interfering in our daily lives. They sit and listen to us here in the coffee shops, in houses, and tap our phone calls. I want the international community to know the real face of Assad and I call on them to protect the Syrian people who will demonstrate.”

Within hours of Assad’s speech, several hundred residents of the coastal city of Lattakia took to the streets to protest. Gunfire was heard and by evening activists in Syria had uploaded a video to YouTube which appeared to have been filmed in Lattakia and showed a man lying flat on the concrete, blood pouring from the wound where a bullet had hit him square between the eyes.

Andrew Tabler, a fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, who spent eight years working in Syria as a journalist and is the author of an upcoming book on the country, said he doesn't think Assad's regime is capable of reform.

“Bashar does not feel he has to change. He might make some changes, but not reform. Yet the winds of change are blowing through the Arab world. Maybe these protests in Syria will not lead anywhere today but in the long term they are a problem for the regime.”

A second GlobalPost reporter, who cannot be named for security reasons, contributed to this article from Damascus.