China-Philippines standoff: Will the US military get involved?

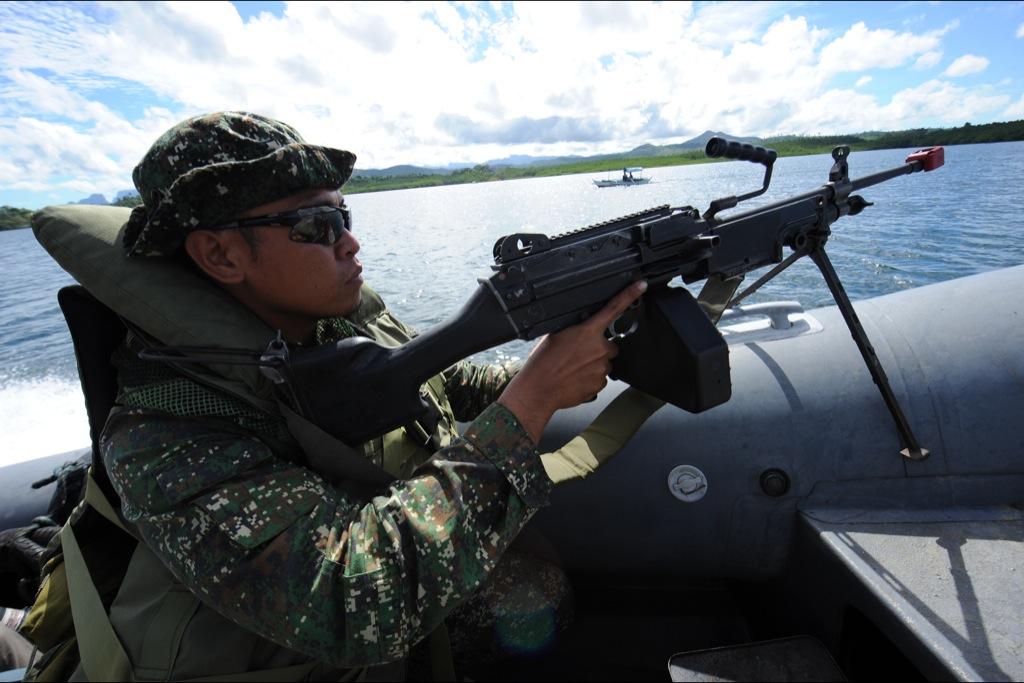

A Philippine marine aboard their boat, conduct security patrol along Ulugan Bay, facing South China Sea in Puerto Princesa, Palawan island, south of Manila on April 25, 2012.

HONG KONG, China — With a US ally engaged in a tense standoff with China over disputed territory in the South China Sea, America risks wading into increasingly perilous waters.

The conflict began in mid-April, when a Filipino frigate — a 1960s Coast Guard vessel bought from the United States — attempted to stop several boats of Chinese fishermen who had taken live sharks, giant clams and coral from waters claimed by the Philippines around a rocky patch called the Scarborough Shoal. The Chinese dispatched several larger, more modern boats from one of its civilian maritime agencies, which intercepted the frigate, allowing the fisherman to escape with their catch. Filipino fishermen say they have since been barred from fishing in the lagoon.

Now, after nearly a month, ships from the two nations have refused to budge from the waters surrounding the shoal, while populists back home have whipped up a nationalist frenzy.

In the Philippines, the office of the president declared that it was unilaterally renaming the disputed land, “Panatag Shoal.” (Chinese call it Huangyan Island.) In China, a video went viral on Wednesday showing a TV anchor pronouncing — falsely — that the Philippines is “Chinese territory,” and that China “has unquestionable sovereignty” over the island nation. Meanwhile, a major general wrote an op-ed urging the Chinese navy to smash the Philippines “with both fists” next time, generating 174,000 responses — the majority of them supportive.

This scuffle is merely one of dozens of overlapping, contradictory claims for territory in the South China Sea, where the nations of Southeast Asia are facing off against an increasingly assertive China — and against one another.

“China certainly shares much of the blame for the current standoff. Its claims to the South China Sea, based on limited historical evidence, do not provide a significant basis to make sweeping, unilateral assertions,” says Andrew Billo of the Asia Society.

More from GlobalPost: Chinese cars, made in Bulgaria

Where does the US fit into this toxic brew of jingoism, nationalism, and disputed territory? Its strategic shift to the Pacific, geopolitical rivalry with China, and alliance with the Philippines have inescapably drawn American interests to the Asian hotspot.

In early May, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton outlined America’s emerging priorities in the South China Sea: freedom of navigation, unimpeded commerce, maintenance of peace and stability, and respect for international law.

Beyond that, the sea plays an enormously valuable role as the international highway of global trade. Half of all the world’s intercontinental goods pass through the South China Sea, amounting to $1.2 trillion in trade with the US every year, according to a January report from the Center for New American Security. And its untapped energy resources are vast: 900 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, and as much as 130 billion barrels of oil are estimated to lie undiscovered beneath the seabed.

“The geostrategic significance of the South China Sea is difficult to overstate,” the authors of the CNAS report write. “The South China Sea functions as the throat of the Western Pacific and Indian Oceans.” Yet, they note, American interests in the region “are increasingly at risk” due to “the economic and military rise of China and concerns about its willingness to uphold existing legal norms.”

Taking any overt action to defend those interests would set off alarm bells in China. Last month, after Americans posted 4,500 personnel to the Philippines — coincidentally during the April standoff over Scarborough Shoal — Chinese critics blasted the US for “meddling” in regional affairs.

More from GlobalPost: After the tsunami

Since then, the US has exercised caution, refusing to take sides in the dispute, even as Manila requested support.

Complicating matters further is the difficulty of weighing the validity of the competing claims.

Since the 1940s, Chinese maps have included a “9-dash line" that encircles nearly all of the South China Sea; Beijing has yet to explain what the line means. Vietnam has meanwhile ramped up its naval power, while proceeding to sell oil rights in disputed territory to Western companies. Belatedly, the Philippines has become more forceful in asserting its exclusive rights to areas — such as Scarborough Shoal — that Chinese fisherman have visited for generations.

Even if they looked to the United Nations for resolution, the International Tribunal for the Law of the Seas has no power to settle disputes over sovereignty. And while diplomacy stalls, fishermen and civilian ships from each country are taking matters into their own hands.

“We’re now running a risk of an accident or confrontation arising from lack of clear instructions on how to behave,” says Carlyle Thayer, professor emeritus at the Australian Defence Force Academy. “The South China Sea is like a bathtub: When you put more ships in it, there’s going to be a collision.”

While efforts are underway in ASEAN, the regional association, to create a binding “Code of Conduct” on the seas, it has proved too feeble to stand up against Chinese pressure. “Some nervous nellies in ASEAN don’t want to confront China,” says Thayer.

So where does that leave the US? In the awkward position of being the final backstop against China, while simultaneously trying to maintain an appearance of neutrality. That means honoring its military commitments to the Philippines, Thayer says, while stopping short of endorsing its allies' assertion of territorial rights.

“The US should continue backing the Philippines," says Thayer. "That’s the weak reed, and if China breaks the Philippines, it will affect other countries’ claims.”

Other experts say that America's main focus should be on guaranteeing the freedom of global trade routes, while leaving the mess of sorting out sovereignty to the states themselves.

“The US should take a step back from the issue,” says Billo of the Asian Society, “It has made its point with respect to its support for a key ally, and the region as a whole, but ultimately it is in the US interest to have regional stability and not allow the conflict to escalate further.”