Can vigilante justice save Mexico?

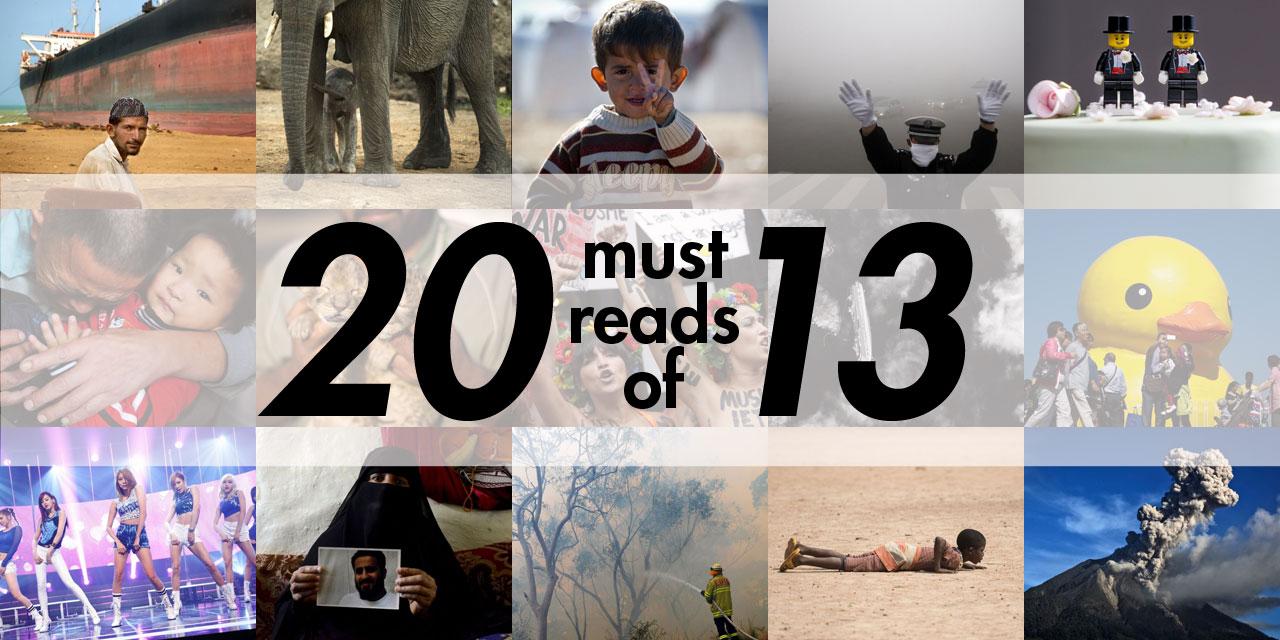

Editor's note: We publish thousands of stories at GlobalPost every year. But some of these don't receive the reader attention they deserve. Our series "20 Must-Reads of 2013" fixes that problem. Here's a look — maybe a second one — at some of our best journalism of the year.

AYUTLA DE LOS LIBRES, Mexico — For almost a month now, hundreds of masked men wielding old shotguns, rifles, revolvers and machetes have claimed to be the law in the rugged mountains outside the faded resort of Acapulco.

Manning roadblocks and patrolling by the truckload, these citizen posses have been rounding up accused drug dealers, rapists, killers and rustlers under the wincing but winking watch of state and federal security forces.

Last week, the vigilantes paraded 54 captured men and women in front of thousands of their neighbors, the vague and unsubstantiated charges against them read aloud over loud speakers.

“Organized crime,” intoned a community leader as the accused were escorted into the covered square in El Mezon, a mostly Mixtec indigenous village belonging to Ayutla township, some 75 miles northeast of Acapulco. “Murder. Rape. Kidnapping. Extortion.”

Despite years of promised reforms, Mexican justice remains cut from the thinnest of fabrics. Tens of thousands of purported criminals rot for years in state and federal prisons as they await trial. The convictions handed down for every 100 arrests can be counted on one hand, academic studies show.

President Enrique Pena Nieto, scarcely two months into a six-year term, has vowed to move away from his predecessor's strategy of military-led offensives against drug trafficking gangs. Instead, the president plans to focus more on the robberies, extortion and violence that affect mostly ordinary Mexicans.

For Pena Nieto to pull that off, Mexican security analysts say he will need better local policing and criminal prosecutions, a high hurdle in much of the country. The villagers in these mountains aren't holding their breath.

“The federal and state governments haven't been able to do anything,” said Evert Castro, an Ayutla municipal councilman. “And we don't have the capacity to fight these criminals. So the people got tired and decided to act on their own. We see this as a good thing.”

Following negotiations this week between community leaders and Guerrero's governor, most of the detainees seem likely to be turned over to state prosecutors.

“They must be subjected to the established laws and institutions,” Gov. Angel Aguirre recently told local reporters in the state capital, Chilpancingo. “We are going to continue working to provide security and confidence so that a climate of harmony returns in communities where this problem is focused.”

But Bruno Placido Valerio, a founder of the volunteer forces that comprise the bulk of the vigilantes, told the crowd last week that the accused would remain in community custody for at least two more weeks, when another public assembly would be held.

“This is not taking justice into our own hands,” Placido Valerio told villagers. “We have to be just.”

Only a handful of the prisoners stand accused of murder and kidnapping. One youth was arrested for tending to three marijuana plants at his house — and for smoking the harvest. Another faces charges of stealing a cow.

“Considering that he's a parasite on society we want him to be judged according to the uses and customs of the people,” intoned the speaker of the supposed rustler, referring to the traditional justice that exists a world apart from official law. Punishment can mean everything from community labor to expulsion.

More than half the prisoners seem to have been taken for being “hawks,” or street corner lookouts, for a local criminal group headed by an Ayutla native known only as “El Cholo.” The gang leader's wife, brother, father and mother were all among the detainees. But Cholo himself had slipped through the dragnet.

The tightly-packed crowd murmured and shook their heads as the vigilantes read the most serious charges. Necks craned for glimpses of particular perpetrators. “He's from my village,” whispered a shotgun-toting man of one alleged murderer. “A fool.”

Anchored by Acapulco — which ongoing gang wars placed it among Mexico's deadliest cities last year — Guerrero state stretches hundreds of miles along the southern Pacific Coast, the high Sierra Madre range running through it like a backbone.

More from GlobalPost: Drug war rages on the edges of Mexico City

Many urban Mexicans have long considered these mountain hinterlands as “untamed.” Popular wisdom holds that the rough and ready people living here are best not riled.

“They call us the wild people,” concedes Evert Castro, the Ayutla councilman. “But it's not like that. This a tranquil area.”

These mountains, however, have earned a sordid place in Mexico's history.

Ayutla was the birthplace of a 1854 rebellion launched against Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, Mexico's dictator of the moment. Then, in the 1970s, a leftist guerrilla movement that swept through the Sierra Madre was eventually crushed by a ruthless military campaign. The state police put down a similar rebellion in 1988.

Police dispatched by a governor ambushed and killed 17 unarmed protesting farmers near Acapulco in 1995. Soldiers in 1998 killed 11 suspected guerrillas and local village leaders meeting at a rural schoolhouse outside Ayutla.

As in much of Mexico, criminals began to besiege Ayutla and other nearby towns about six years ago, when gangster violence erupted along the US border and down both coasts.

Kidnappings, extortion and murders all spiked. Unemployed people started using cocaine, methamphetamine and other drugs, many of them going to work for the dealers as lookouts, sellers, even assassins.

“It was very quiet here and then from one day to the next it seemed to all go bad,” said Celerina Garcia, a housewife taking in the late afternoon air at Ayutla's crowded plaza. “You couldn't leave your house at night.”

Garcia and other residents say things have calmed considerably since the vigilantes started patrolling. In addition, hundreds of state and federal police, as well as soldiers, have set up highway checkpoints of their own in recent days, keeping a wary but respectful distance from the village militiamen.

As planting season approaches, ongoing talks with the governor aim to return the armed farmers to their plows.

“We are going back to the fields but we are not going to give up our weapons,” Placido Valerio told the assembly last week. “We are going to start building a system of justice."

More from GlobalPost: Latin America tells the US 'drop your weapons'

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!