Why Mexico’s celebrity anti-globalization rebel is quitting

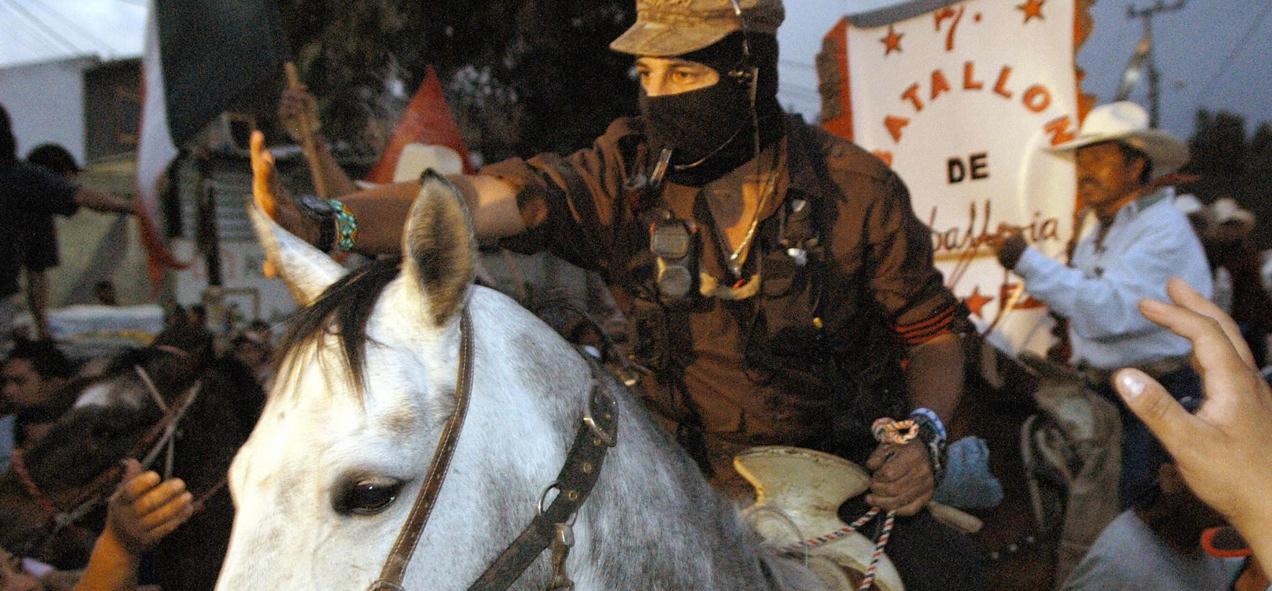

The leader of the Mexican Zapatista Army for National Liberation, Subcomandante Marcos, in San Salvador Atenco, Mexico State, April 2006.

The leader of the Zapatista rebels known as Subcomandante Marcos gained worldwide fame giving interviews in a ski mask and smoking a pipe. He appeared before photographers on horseback with ammunition belts across his chest. And he launched a national speaking tour riding a motorcycle with a Mexican flag sticking out the back.

So it came as a little surprise that when he stepped down from the helm of the Zapatistas, after being their most visible figure since they rose up in 1994, it would be with some fanfare.

Still, the lengthy resignation letter that Marcos read out last weekend in a jungle Zapatista village called La Realidad — or Reality — left some head scratching.

In the speech that was posted on the rebels’ website, Marcos said squarely he would no longer speak for the Zapatista movement, before announcing that he had been a hologram, and that illusion would cease to exist.

“It was a terrible, marvelous magic trick,” he said. “Those who loved and hated Marcos now know that they hated and loved a hologram. Their love and hate has been, well, useless, sterile, empty.”

The ski-masked rebel went on to say he was now named “Galeano,” after a Zapatista teacher who was recently murdered. But he then called on the crowd to see who else would call themselves Galeano to a chorus of shouts.

The tricky message quickly unleashed a river of interpretations over what Marcos meant and speculations of what he might do next.

Is Marcos preparing to take his mask off, move to Mexico City and reintegrate into mainstream society, pundits wondered. Or will he stay in the jungle, still supporting the Zapatistas in the new role of Galeano? Or will he disappear from all public life, to pass his retirement in a secret location?

“The only person who really understands Marcos’ strategy is Marcos,” said Mexican historian Lorenzo Meyer. “He likes to talk in riddles. To leave people guessing.”

The rebel’s announcement also reignited a debate on the guerrilla leader and his movement that has been flaming on and off for two decades.

Marcos became an icon to many on the left, in Mexico, South America, the United States and Europe.

The Zapatistas rose up in 1994, challenging the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), and the rebels were major symbols in the anti-globalization movement of the following decade.

The image of Marcos’ eyes staring through his ski mask are reprinted on T-shirts. In downtown Mexico City, vendors sell posters of Marcos alongside images of Che Guevara and Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa.

To many, Marcos has offered something new and different in Mexico’s staid politics, his poetry and posturing stirring up the pot.

“He was original and fresh and he has kept a pure position,” says Raul Benitez, a researcher at Mexico’s National University, who has written on the rebels. “He has led the Zapatistas well and he doesn’t hurt people.”

However, others accuse Marcos’ image of being self-serving and frivolous.

“Marcos even became a sexual fantasy for good girls who were getting old,” wrote journalist Alejandro Cacho, in a column entitled, “The Imposture of Subcomandante Marcos.”

Identified by Mexico’s intelligence services as being Rafael Sebastian Guillen, the Zapatista commander is reported to come from a middle-class family in the northern state of Tamaulipas.

He went to Mexico City to study philosophy at a time of student radicalism in the 1970s and joined a Maoist revolutionary group. He then went to Mexico’s southern state of Chiapas to foment revolution among indigenous Mayan groups in the mountains and jungles.

While not indigenous himself, Marcos spent years building the trust of Mayan activists and community leaders — a story reminiscent of “Lawrence of Arabia.” In his statements, Marcos often refers to “we” indigenous.

This association with the needs of Mexico’s oppressed indigenous people is a central part of Marcos’ appeal.

“The indigenous issue garners strong emotional reactions in Mexico. On one side, there is pride with the pre-Hispanic civilizations, on the other there is guilt about the poverty of indigenous people today,” the historian Meyer says. “Marcos knows how to handle the issue well.”

Marcos has also gained supporters by being largely pacifistic. While the Zapatistas waged an armed uprising in 1994, most fighting finished after 12 days.

Since then, the Zapatistas have focused on building their “villages in rebellion” with alternative schools and health clinics, rather than shooting at soldiers.

Amid this “pacifistic uprising,” Marcos has had time to write several books, including a novel that he co-wrote with acclaimed Mexican author Paco Ignacio Taibo II.

Such literary skills helped carry the Zapatistas’ message around the globe. But in his resignation speech, Marcos conceded that the focus on him and his personality could distract from the struggles of the poor Mayans he represented.

This, he claims, was why he had to move on.

The Zapatistas are firm in saying they will continue their struggle, but without the pipe-smoking guerrilla leading the charge. It is unclear, who will replace him as the rebels’ leading voice.

“The case is that Marcos went from being a spokesman to a distraction,” Marcos said. “The character was created and now its creators, the Zapatistas, can destroy it.”

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?