The truth about America’s Mandela policy

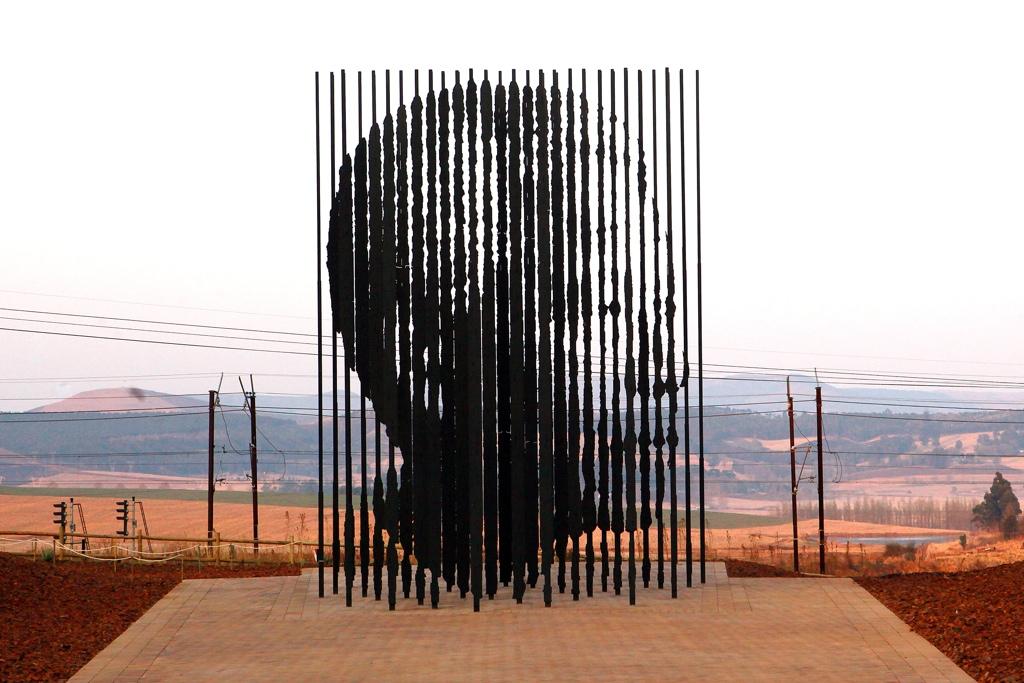

A sculpture of Nelson Mandela.

BUZZARDS BAY, Mass. — As the world mourns Nelson Mandela, international leaders, including US President Barack Obama, gathered in Johannesburg to honor the legacy of the South African freedom fighter and reconciliation icon.

Obama eulogized Mandela as “the last great liberator of the 20th century.”

But Washington has not always praised South Africa’s first black president in this way.

As recently as 2008, Mandela required a special State Department waiver to enter the United States — his name was on a terrorist watch list.

Much ink has been devoted to Mandela’s revolutionary past since his death on Dec. 5, at age 95. Many want him remembered not as a saint, but as a full-blooded man whose metamorphosis from rebel to hero came during his more than 2 1/2 decades in prison.

But as Mandela broke rocks and mined salt on Robben Island, the United States government apparently thought he was right where he should be.

President Ronald Reagan vetoed a bill to impose sanctions on the South African government, even as world powers applied pressure on Pretoria’s white rulers and the “Free Mandela” cause swept the globe.

A bipartisan group of congressmen overrode the veto.

The Republicans in Washington who broke with Reagan included former House Speaker Newt Gingrich and Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell. They defied a president of their own party so they could be, in the words of Republican Sen. Richard Lugar, “on the right side of history.”

At the time, apparently to some, it still was unclear on which side of history Mandela would lie.

The rhetoric against the anti-apartheid leader and his African National Congress (ANC) came straight from the Cold War playbook. Mandela’s ANC was seen as being dangerously close to the Soviet Union, and Mandela himself had been a member of South Africa’s Communist Party.

Mandela also embraced Fidel Castro and his Cuban Revolution, which served as inspiration for the ANC’s own aims. This alone would have put him beyond the pale for many Americans.

When Mandela was finally let out of prison in 1990, conservative commentator William F. Buckley ominously warned, “the release of Mandela, for all we know, may one day be likened to the arrival of Lenin at the Finland Station in 1917.”

Today, the outpouring of praise for the man might say otherwise.

Instead, just months after Mandela’s release and before his planned US tour, reports emerged that the CIA had played a key role in his 1962 capture. Many had suspected that much all along.

Whatever did Americans see in South Africa’s oppressive state?

The country was a valuable trading partner, a source of gold and other minerals vital to the economies and lifestyles of the developed world.

Most important, its defenders said, it was a bulwark against communism.

The policy of supporting the apartheid regime was called “constructive engagement,” which, while it may sound a bit hypocritical today, does not have quite the sanctimonious ring of some other US foreign ventures.

When the CIA intervened in Guatemala in 1954 to topple the democratically elected president, Jacobo Arbenz, it did so in the name of saving civilization. Arbenz was directing land reforms that threatened the fortunes of the United Fruit Company, a corporation in which many Washington power brokers were heavily vested, including the spy agency’s director, Allen Dulles.

This and other escapades are outlined in detail in Stephen Kinzer’s recent book The Brothers: John Foster Dulles, Allen Dulles, and Their Secret World War.

The list goes on.

The CIA’s overthrow of Iran’s Mohammad Mossadegh in 1953, which would save Iran’s oil for the British, was also done in the name of the fight against communism.

Unquestioning support of the mujahedeen during the anti-Soviet jihad in Afghanistan during the 1980s was also an anti-communist measure — what was bad for Moscow had to be good for Washington.

Afghanistan was certainly disastrous for the Soviets, but few would argue that arming the future Taliban turned out well for the US.

So, what about Mandela carrying the terrorist label so long?

After all, Gerry Adams, leader of Ireland’s Sinn Fein Party, who has shown less of Mandela’s drive toward healing and reconciliation, made it off the watch list two years earlier in 2006.

Some US officials treated the South African’s listing as a minor oversight.

Former Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice called it “embarrassing.”

Her predecessor, Colin Powell, sounded baffled last week when a BBC interviewer brought it up.

“I saw that little factoid and it’s kind of astonishing. But I don’t think that was deliberate, I think nobody got around to taking him off the list,” he said.

Pressing further, the interviewer said, “I guess people would say those who saw him as a terrorist just got it wrong.”

“Well, no,” Powell replied, explaining that “terrorist” was an appropriate label for the “violent acts” Mandela and the ANC carried out.

Hear the full Powell interview below.

Indeed, as Mandela wrote in his 1994 autobiography, “when a man is denied the right to live the life he believes in, he has no choice but to become an outlaw.”

The South African leader was no fan of Washington’s international hubris, something he made clear in an interview with Newsweek in 2002.

“There is no doubt that the United States now feels that they are the only superpower in the world and they can do what they like,” he said.

These are words that may be hard for Americans to hear, but they are just as important as the civil rights hero’s more palatable utterances.

Rest in peace, Madiba.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?