Mars Curiosity rover finds water on Mars

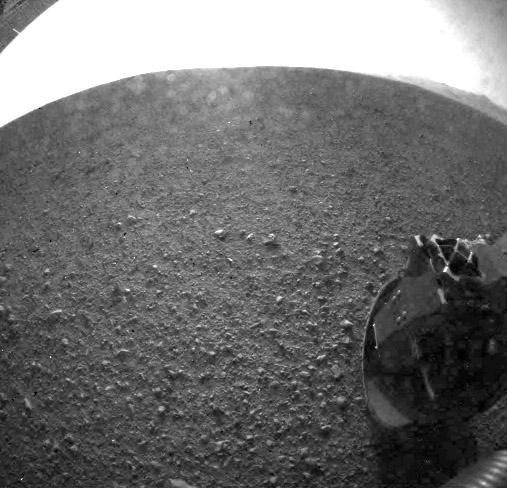

IN SPACE – AUGUST 5: In this handout image provided by NASA/JPL-Caltech, one of the first images taken by NASA’s Curiosity rover, which landed on Mars on the evening of August 5, 2012 PDT and transmitted to Spaceflight Operations Facility for NASA’s Mars Science Laboratory Curiosity rover at Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California. The MSL Rover named Curiosity is equipped with a nuclear-powered lab capable of vaporizing rocks and ingesting soil, measuring habitability, and whether Mars ever had an environment able to support small life forms called microbe. (Photo by NASA/JPL-Caltech via Getty Images)

NASA's Curiosity rover has discovered water in Martian soil samples that could be enough to assist future astronauts who might someday visit the red planet, according to an academic paper published in the peer-reviewed September issue of Science.

To be clear, there's no running stream or secret underground well of water miles below the surface. Instead, water molecules were discovered bound to other minerals in fine-grained soil.

"The first scoop of soil analyzed by the analytical suite in the belly of NASA's Curiosity rover reveals that fine materials on the surface of the planet contain several percent water by weight" a press release stated.

Each cubic foot of soil has about two pints of water, which according to researchers means two percent of Martian soil is basically water.

"We tend to think of Mars as this dry place – to find water fairly easy to get out of the soil at the surface was exciting to me," Laurie Leshin, lead author of the paper and dean of science at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, told the Guardian.

"If you took about a cubic foot of the dirt and heated it up, you'd get a couple of pints of water out of that – a couple of water bottles' worth that you would take to the gym," she added.

These recent findings support earlier evidence found back in June, when Curiosity discovered clay that is formed in water. In addition, geographic formations on the planet also suggest that at one time there may have been water on the planet.

The discovery may prompt some to wonder if it isn't a clue suggesting life on Mars might have been or currently be possible. According to Leshin, that's not likely, though the search continues.

"Although we found water bound up in the soil particles, it's still pretty dry. Also, we didn't find evidence of organic molecules in the soil," she told Gizmodo. So, this doesn't have a very big bearing on the life on Mars discussion. However, we now know that our instruments are working beautifully, and our next step is to drill into rocks that may have been better places to preserve evidence or organics and of wet environments that could be suitable for life."

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!