Indonesia’s underground atheists lay low after Facebook post that led to imprisonment

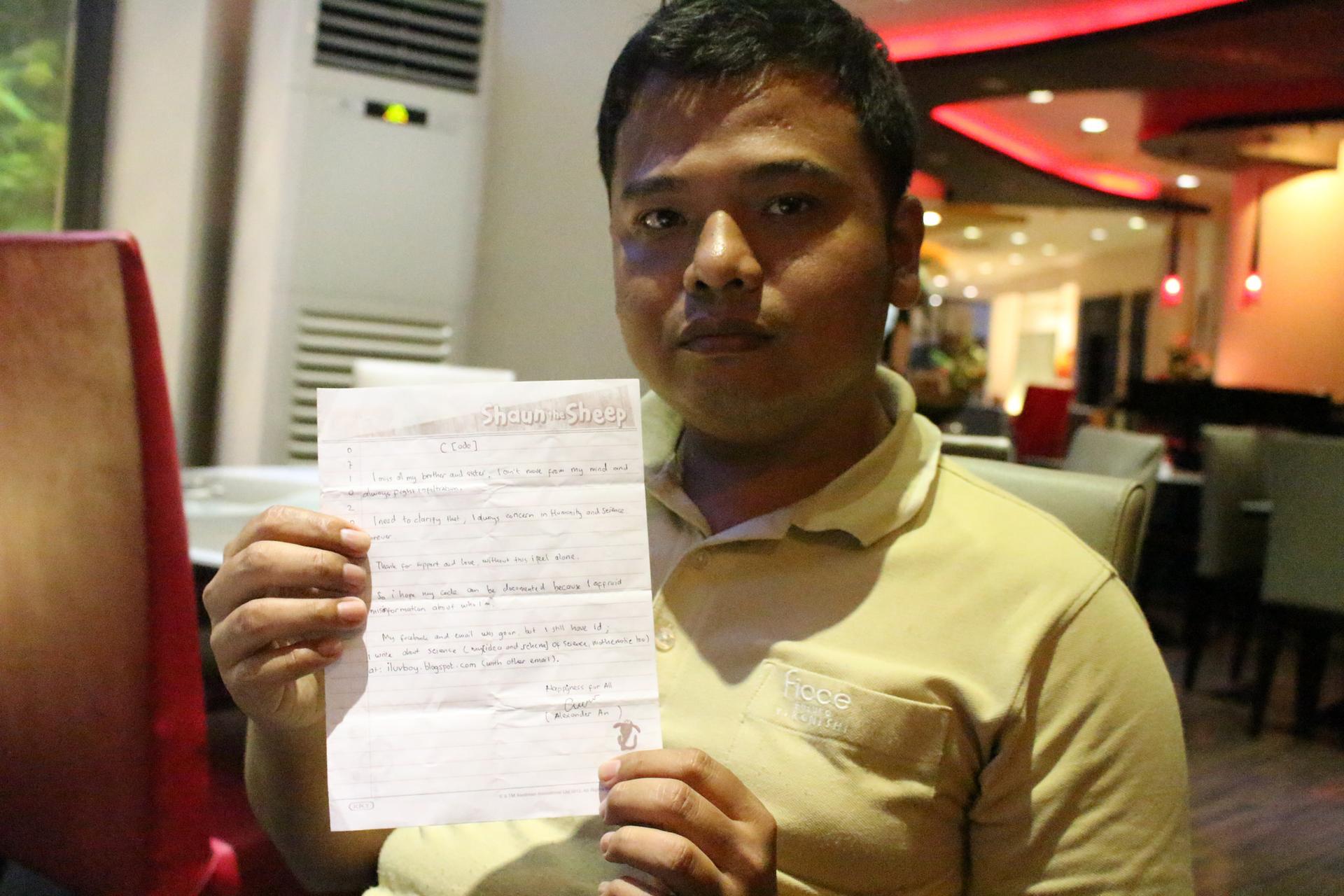

Alexander Aan, 34, holds a letter he wrote to his family from prison. He was incarcerated for two years after running afoul of Indonesia's blasphemy law by posting on Facebook that "God does not exist.”

YOGYAKARTA, Indonesia — As the call to morning prayer rings out over Yogyakarta at sunrise, Arimbi prepares herself for a long day of classes and waitressing at a local cafe.

Wrapping herself in a bright blue hijab, the 26-year-old climbs onto her motorbike and heads to the Islamic university where she studies community development. But Arimbi has a secret she keeps from her classmates, professors and all but her family and closest confidants. She’s an atheist.

While Indonesia is often celebrated as one of the world’s few Muslim-majority democracies, non-religious people say the country’s tough anti-blasphemy laws force them to live a façade of faith, masquerading as Muslims when many spend hours a day mocking religion in private online forums.

But millennial-aged atheists like Arimbi are growing bolder, trying to change national opinions on atheism by living as openly as possible while avoiding jail time. She said she wears the hijab on her college campus, Universitas Islam Negeri Sunan Kalijaga Yogyakarta, and when visiting her strict Muslim father, but only out of respect for her classmates and family. Arimbi said walking away from Islam in her late teens was the most liberating choice she’s ever made.

“I’m free,” she said. “That’s the first feeling I had when I became atheist. I never felt sad. My mind is open and I can finally be free.”

However, the anti-blasphemy laws prevent Arimbi and other atheists from publicly expressing ideas that counter any of the state-approved religions.

This state ideology, also known as Pancasila, grants protections for six recognized religions — Islam, Protestantism, Catholicism, Buddhism, Hinduism, and Confucianism — but also declares Indonesia a monotheistic nation. That means atheism is not an accepted form of spiritual expression.

For advocates like Arimbi, it’s a constant struggle for recognition and freedom to be irreligious.

“The blasphemy law is hurting our rights as citizens. The government needs to be clear about Pancasila [and how it relates to minorities] and then make laws to protect us,” said Arimbi.

And who better to spread this message of religious freedom than Arimbi? Raised in a conservative Muslim home, Arimbi quickly grew into a devout Muslim, learning to read the Quran as a young child.

Convinced that the whole world should experience Islam and Sharia law, Arimbi became radical, enlisting in the Muslim extremist group Hizb ut-Tahrir at the age of 18.

Known for its staunch anti-Israel views and recent military interference during the civil war in Syria, Hizb ut-Tahrir is designated in many countries as a terrorist organization.

“We were taught to fight for a caliphate [Islamic state] and share our views with others,” she said. “I heard the men received military training…They were quite radical actually, jihadists.”

However, Arimbi began doubting her devotion to the group when her questions about the plausibility of a global Islamic state went unanswered.

“I always wanted to know how we can change the system without a coup d’etat and they had no answer for me,” Arimbi said. “I was confused and felt something was wrong. I thought, ‘Is this really coming from God?’”

Moving to Yogyakarta for college in 2009 did nothing to ease her doubts.

“If the Quran is true, there should only be one tafsir (interpretation). If not, the possibility is so large for you to make a mistake,” she said.

In Yogyakarta, Arimbi befriended liberal Muslims who echoed her sentiments about the infallibility of the Quran and the Hadith, which summarizes the teachings and acts of the Prophet Muhammad.

“It’s terrible, there’s no methodology to check whether it is really coming from Muhammad,” she said.

Unable to find any answers in her community about the existence (or lack thereof) of God, Arimbi turned to another social network: Facebook.

She joined a private Facebook group for Indonesian atheists and started having underground conversations with other like-minded people.

“She was already quite critical when she joined the group,” said Karl Karnadi, who started Indonesian Atheists (IA) in 2008 for fellow non-believers like himself.

Karnadi, who now works for Facebook in San Francisco as a software engineer, said Arimbi started asking questions right away and even began moderating discussions.

Six months later, Arimbi made the decision to come out as an atheist to her family.

“My father cut off my financial support so I have to pay for college myself,” she said. “My younger brother and sister are liberal Muslims so they help me out…But it’s very hard being atheist in Indonesia.”

Statistics on religion in Indonesia help show why that is.

A 2010 poll by Pew Research Center revealed that nine in 10 Indonesians think the influence of Islam in politics is a positive thing. Likewise, 30 percent of Indonesians said they were in favor of sentencing to death those who abandon the Muslim faith.

Lukman H. Saifuddin, Indonesia’s minister for religious affairs, maintains that atheism is not illegal. However, he also acknowledged that the laws are vague and open to interpretation. Asked whether self-identifying as an atheist online was considered blasphemy, Saifuddin quipped, “the courts will decide.”

“As long as there are no complaints and no individuals are being forced to convert, it shouldn’t be a problem,” he said. “But spreading atheism [even online] is illegal.”

Alexander Aan understands better than most how Indonesia’s blasphemy laws work.

Aan’s conviction made international headlines in 2012 after an Indonesian court found him guilty of “stirring up hatred” when he posted on his personal Facebook account that “God does not exist.”

The former civil servant from West Sumatra spent nearly two years behind bars and is still putting his life back together since his release in 2014.

“People told me I was just looking for a sensation,” said Aan, 34, who now teaches math to make a living. “But I have a duty to let people know we are one. In religion, people are so exclusive. On Facebook, I was very aggressive against the idea of exclusiveness. It made the religious people hate me.”

In fact, a mob confronted Aan at his government job, demanding to see his Facebook account after a former friend reported him to authorities. Police arrested Aan after finding the brief post that declared his religious disaffiliation.

“They forced me to beg to Islam for forgiveness like a child,” he said. “I just felt alone and thought all Indonesians hated me. I was very depressed.”

Rafiq Mahmood is a member of Atheist Alliance International, which supported Aan throughout his conviction and imprisonment. Mahmood himself was Muslim for 40 years before “converting” to secular humanism. He remembers Aan’s trial vividly.

“The court said Alex was not a criminal — but that he must go to prison,” said Mahmood. “We’re not safe here. And because of Pancasila, the law cannot allow atheism.”

Mahmood expects millennials will change the country as globalization slowly affects how young adults in Indonesia view equality and democracy.

“They can’t run away, some of us have to stay behind and support each other so we can try and make this world more enlightened,” he said. “We have to fight for it.”

Due to so much religious pressure, many atheists like Aan choose secrecy to survive.

“It’s difficult to pretend with my family. I don’t care about others, but with my family it’s difficult,” said Aan, who said he lives separately from family and leads them to believe he is still Muslim.

For Arimbi, the same holds true. While her family does know about her atheism, she does not argue the point in order to keep the peace.

“Believing in God is very holy here, but I would not leave my family. Boyfriends and friends will leave you, but my family still accepts me,” she said. “Maybe I sound like a fool, but I love them.”

This story is presented by The GroundTruth Project.