India: A primer for the biggest elections in world history

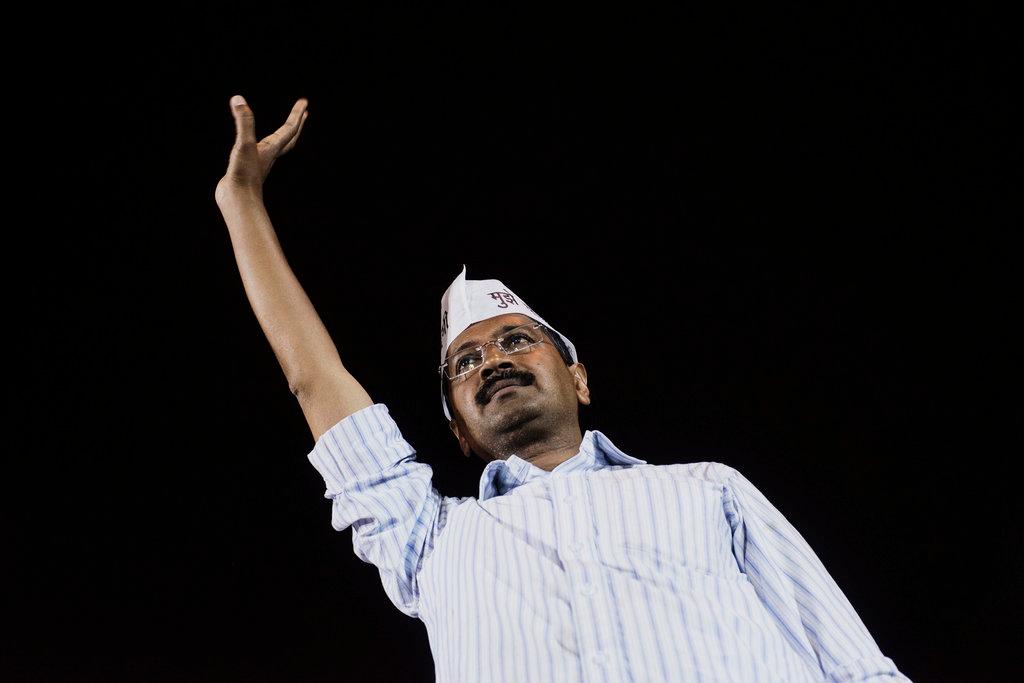

Arvind Kejriwal, leader of Aam Aadmi Party (AAP), waves at this supporters during an election campaign rally in North West Delhi.

MUMBAI — On Monday the world’s largest democracy began the six-week process of electing a new government. Here’s what you need to know before the 16th Lok Sabha (lower house of parliament) — which itself will determine India’s next prime minister — is chosen.

The Voters

This year, an estimated 814 million Indians are eligible to vote, according to the Election Commission of India. That includes about 120 million first-time voters from 2009, when the last Lok Sabha was elected. And 52 percent of eligible voters are between 18 and 40 years old.

The huge size of India’s electorate is the reason voting will take place over five weeks, including votes from approximately 930,000 polling stations employing as many as 11 million people and using 1.4 million electronic voting machines.

Twenty-seven percent of Indian voters are illiterate and will choose their candidate by party symbol.

On April 7, the first booths open in the northeastern states of Assam and Tripura. And the polls close on May 12 in Bihar, Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal, states with some of the highest numbers of parliamentary seats and most hotly contested races. Results will be announced May 16.

The Money

Politicians campaigning for the 2014 general election will spend an estimated $5 billion, according to the Centre for Media Studies. This makes it the most expensive election India has ever seen — more than triple the amount spent by candidates in 2009 — and it rivals the record-setting $7 billion price tag of the 2012 US presidential election.

Politicians are only allowed to spend up to seven million rupees, or $114,000 each in the run-up to the election, according to Indian campaign finance regulations. But as shown by the ubiquitous and expensive billboard and newspaper ads across the country, few adhere to the rules.

The Parties & Alliances

Of the 1,600 or so registered political parties, six are considered national parties.

No single party really expects an absolute majority, which requires 272 of the Lok Sabha’s 543 seats. So parties tend to form alliances to assemble a majority in the lower house, which in turn selects the prime minister.

Most parties partner with one of two broad coalitions, the center-left United Progressive Alliance and the center-right National Democratic Alliance. Each is dominated by a prominent national party.

Indian National Congress

The oldest of India’s political parties, Congress is left-leaning and headed by Sonia Gandhi. She is the latest in a line Gandhi family members to lead the party, stretching back to Jawaharlal Nehru, the country’s first prime minister. A Gandhi-Nehru family member has ruled India for 49 of the 67 years since independence.

The incumbent Congress party favors progressive policies like subsidies for the poor, protections for minorities and job training for unemployed youth. In this election, the Congress has been dogged by corruption charges (more on that below) and blamed for the country’s economic woes.

Bharatiya Janata Party

The BJP is a right-wing party founded in 1980 by proponents of Hindu nationalism, or Hindutva. The party has held one full term in power — from 1998 to 2004 — when the BJP-led National Democratic Alliance held office. Since then, the BJP has remained the dominant opposition to the Congress. Last December, BJP candidates unseated incumbents from Congress in four state elections, which many view as a harbinger of the upcoming election results.

Aam Aadmi Party

Although it’s not a national party, the Aam Aadmi Party (“Common Man Party”) is a newcomer to the country’s political scene and made a splash in December’s state elections. Running primarily on an anti-corruption agenda, party leader Arvind Kejriwal became chief minister of Delhi but resigned in February after just 49 days in office, citing the failure to pass his keystone anti-corruption bill. The party has galvanized youth voters and is seeking to become a legitimate national force in this election.

Bahujan Samaj Party

The BSP, as it’s called, is a national party anchored in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh. With about 134 million voters, UP is India’s most populous state and accounts for 80 seats within the Lok Sabha. The BSP draws most of its support from Dalits, or untouchables, and voters from other lower castes. Lead by Mayawati, the BSP has offered forceful critiques of both leading parties but has refrained from aligning with either.

The Candidates

Narendra Modi is the current chief minister of Gujarat, a state in northwest India, and the BJP’s prime minister candidate. He’s credited with implementing neoliberal economic reforms in Gujarat, spurring the state economy to double-digit growth and wooing multinational corporations to set up shop there. But Modi faces allegations that as Gujarat’s chief minister, he abetted violent riots there between Muslims and Hindus in 2002. More than 1,000 were killed in the riots, but the Supreme Court exonerated Modi of any wrongdoing.

Rahul Gandhi is the vice president of the Congress Party and son of party leader Sonia Gandhi. Despite his family lineage — his father, Rajiv Gandhi was prime minister before his 1991 assassination — Rahul, 43, faces allegations that he lacks experience. Although his portrait is emblazoned on campaign materials, he hasn’t officially been declared the party’s candidate.

The Issues

Economic development and corruption are the top two issues for Indian voters, according to a nationwide survey conducted by the University of Pennsylvania’s Center for the Advanced Study of India.

Economic Development

With the national economy growing at a rate of 4.7 percent last quarter, the seventh consecutive quarter below 5 percent growth, India seems further than ever from regaining the more than 8 percent growth rate it enjoyed for much of the last decade.

Much of the blame for this slump has been placed at the feet of the current government, the Congress-led UPA alliance. In contrast, the BJP has campaigned almost purely on a platform of economic development and reform, citing Modi’s success in Gujarat as the basis for a national economic plan.

Although many analysts actually see little difference between the economic policies of the Congress and the BJP, the messaging strategy of the latter seems to have worked so far: Of those voters who supported Congress in the last election and plan to vote for BJP this time around, 35 percent say the economy is their top concern, according to the CASI survey.

Corruption

More than one in two Indians reported paying a bribe when accessing public services and institutions in the last year. That’s twice the global average, according to the Global Corruption Barometer 2013. And the institution found to be the most corrupt? Political parties.

Dirty deals between politicians and the private sector — such as the 2G telecoms scam, in which favorable contracts were given to companies with close ties to elected officials — cost the country billions of dollars. But the most pervasive form of corruption is the relatively small bribes the police demand from average citizens on a daily basis.

Speaking out against corruption is standard campaign rhetoric for basically every party, but the feeling on the street is that Congress is too entrenched in the old system to affect real change. For some, the Aam Aadmi Party’s anti-corruption agenda presents a promising alternative.

This story is presented by The GroundTruth Project.

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?