The collective trauma of James Foley and Steven Sotloff’s deaths

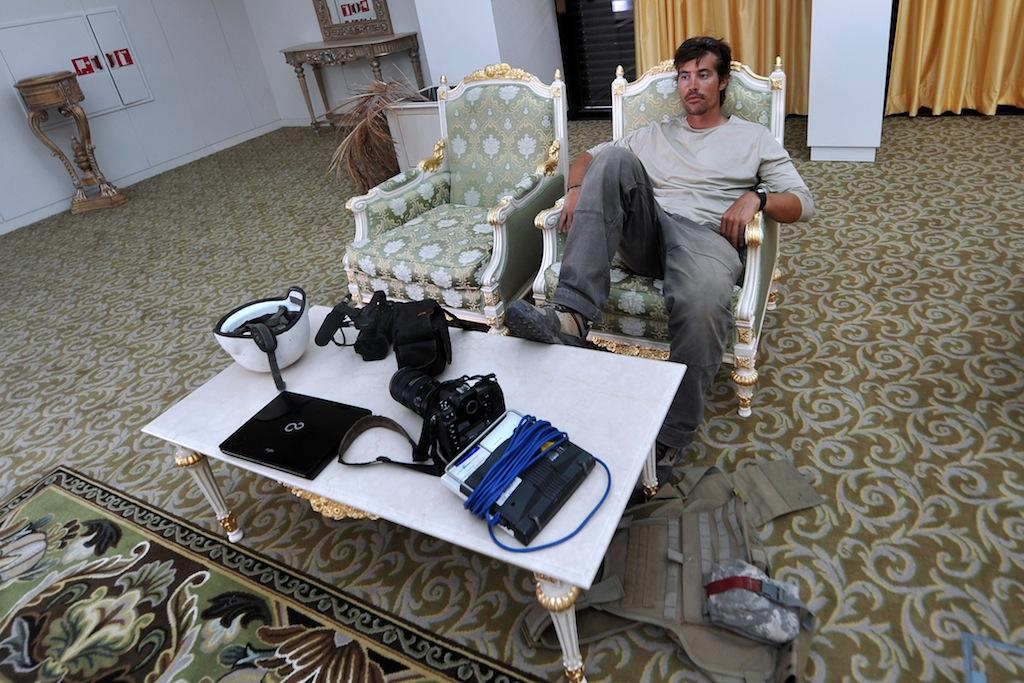

A photo taken on September 29, 2011 shows US freelance reporter James Foley resting in a room at the airport of Sirte, Libya.

BOSTON — I didn’t know Jim Foley.

We weren’t colleagues in the field and there are no stark photos of the two of us all dusty from covering a war. In fact, I have never covered a war.

But several weeks ago when a video was released showing his captors beheading him, I felt, like many other young journalists, that it was a personal loss.

I know I wasn’t alone. He somehow belonged to all of us who want to do the kind of journalism he did. And to all of us who want to dare to think about taking some risks and diving into difficult stories, shining light on injustice and violence. It feels that the collective trauma from his killing has echoed beyond the journalism community.

I found myself reading about him, his final journalism pieces, and his address to students at Medill School of Journalism. I clicked through old pictures of him; desperate to replace the last image of him that the Islamic State had released — of a pale man with a shaved head, dressed in a bright orange jumpsuit that hung outlandishly from his body. I wanted to own my own memory of him, and deny that of IS.

Comfort could be sought in tributes that his friends — mostly other journalists — posted about him.

“A stubborn journalist,” said one reporter.

“An inspiration,” said another.

A stranger to Foley, much like me, posted on the "Remembering Jim" tribute page, “I did not know Jim, but I can’t get him and his family out of my thoughts.” A statement that a group of Syrians were photographed holding up became popular across social media. “Humanity is proud of James,” they wrote.

What is it about these gruesome incidents that brings together different communities — families and friends, journalists, Americans, a larger community of global witnesses — in their combined suffering and resilience?

For Jim’s immediate friends, the answer is deeply personal. But as the concentric circles of his mourners grow wider, the reasons become more varied.

For many journalists who didn’t know him, the reaction could be one of projected fear, or grief.

“Clinically, research on trauma tells us that any violent event with which a journalist feels a personal identification or connection increases the risk of developing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) from the cumulative weight of assignments,” said Bruce Shapiro, executive director of the New York-based Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma.

According to PTSD Alliance, a collective of professionals and advocacy groups, the estimated risk for a person to develop PTSD when witness to killing or serious injury is 7.3 percent. “For people who cover conflict, it’s a very small, close-knit community who rely on each other — it’s devastating," said Judith Matloff, a veteran conflict reporter, editor and author. “When somebody is killed in such a horrific way, it has such a ripple [effect] on so many people’s emotions.”

Yet, journalists have a powerful history of responding to the deaths of colleagues with a “sense of mission toward our own community,” said Shapiro.

He described how Tim Hetherington’s murder in Libya spurred his friends to form RISC, a program to train freelancers in first aid and coping in hostile environments. Shapiro listed other examples: The mass murder of 34 journalists in the Philippines in 2009 that provoked an anti-impunity campaign; the large-scale protests organized by journalists in Mexico in recent years in response to the assassinations of colleagues. Even as far back as 1977, when American investigative reporter Don Bolles was assassinated in Phoenix, over three dozen reporters from 23 newspapers all over the country descended on Arizona to finish his work and identify his killer.

“When confronted with the murder or death of a colleague,” said Shapiro, “journalists often feel motivated to act.”

Whether it is by turning their profiles black on Facebook in tribute to Foley’s work or sharing their best memories of working with him, response from other journalists has been forceful, insistent. “Even those who do no foreign or conflict reporting are mourning and looking for a way to respond,” said Shapiro.

A similar reaction rose up from Rochester in New Hampshire, where Foley’s family lives. Business owners — many of whom didn’t even know the Foleys — put up signs outside their shops in solidarity with the family. In a show of support reminiscent of the Iran hostage crisis, sympathy for the Foley family poured out on social media, blogs and in comment sections of news reports.

In 1979, a group of more than 50 American diplomats were held in captivity in Tehran by Iranian students. The 444-day confinement was said to have “the American people more united than they have been on any issue in two decades,” and prompted the beginning of the ABC series “Nightline.”

At the time, the hostages received Christmas letters in bundles from a global audience waiting for their release. Once home, presents poured in for the survivors, including lifetime passes for major league baseball games. They went through a lot, but by comparison they were treated far better than Foley or the others held with him. They all came home. That memory of “America held hostage” seems a long-ago bookend to the age of terror in which we live.

As images of people all around the world holding up posters that said “Remembering Jim” were published on the internet, it seemed possible that the hurt would heal.

And then it started all over again with Steven Sotloff.

More from GlobalPost: War reporting in the time of the Islamic State

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!