Analysis: Is The Hague racist?

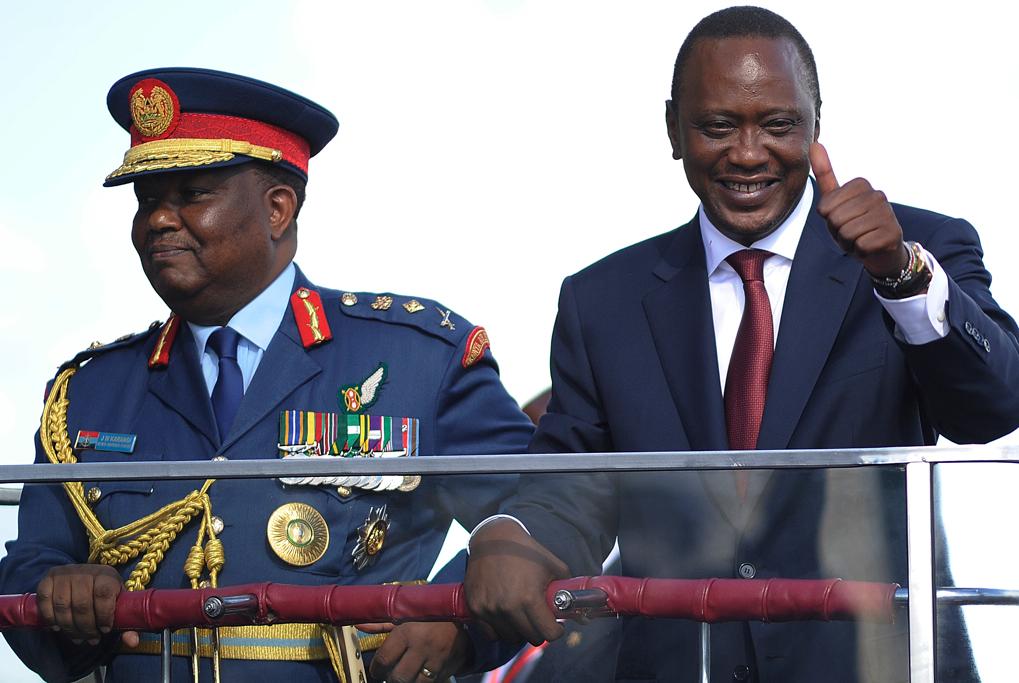

Kenya’s fourth President Uhuru Kenyatta (R) gives the thumbs up after being sworn-in April 9, 2013 in Nairobi. He is also facing trial on charges of crimes against humanity.

NAIROBI, Kenya — As the African Union celebrates its 50th anniversary, its position on the International Criminal Court (ICC) shows how little has changed from the bad old days when its members’ fondness for looking after each other at the expense of their people earned it the nickname the “Dictators’ Club."

Dictators are harder to find nowadays, but clubbable leaders are still commonplace. As a continental body the AU has in recent years become a more benign presence and has notched up some remarkable successes, notably in Somalia where its peacekeepers have had unprecedented success in pacifying a violently wayward nation.

But the AU complaint that the ICC is a racist institution hunting down Africans because of the color of their skin shows that prickliness and misplaced loyalty are not things of the past.

“The African leaders have to come to a consensus that the process the ICC is conducting in Africa has a flaw,” said Ethiopian Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn at the AU summit in Addis Ababa at the weekend. “The intention was to avoid any kind of impunity, but now the process has degenerated into some kind of race hunting.”

The ICC has indeed opened cases in eight countries, and every single one is in Africa.

But that’s not the end of the story.

The governments of Uganda, Democratic Republic of Congo, Central African Republic and Mali are all signatories of the Rome Statute, the legislation that established the court in 2002, making them member states. In a clear admission of their own inability to deliver justice, all four invited the prosecution to open investigations.

Nearly a third of current ICC member states are African.

In the case of Darfur, in Sudan, and Libya, neither of which are ICC member states, prosecutors were asked to investigate by the United Nations Security Council.

The African states of Benin and Tanzania were among the 11 in favor of the Darfur referral in 2005. Gabon, Nigeria and South Africa were among the countries that voted unanimously for the Libya referral in 2011.

In both Ivory Coast and Kenya, the office of the court’s prosecutor opened investigations of its own volition. In Ivory Coast, the government of President Alassane Ouattara welcomed the investigation. In Kenya, it only began after Kenya’s lawmakers failed repeatedly to set up a local tribunal, and after Kenya’s police and judiciary failed to even begin investigations of their own.

In every case, African states and therefore African leaders have played a key role in ushering in the ICC process.

But now that those investigations have, in some cases, resulted in indictments against their own — President Omar Al-Bashir of Sudan is wanted for genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity, while President Uhuru Kenyatta of Kenya is accused of crimes against humanity — they are changing their minds.

At last, Africa’s powerful leaders are faced with a court they cannot bend to their will, bribe or kill, and they don’t like it.

Writing in Kenya’s Daily Nation newspaper columnist Macharia Gaitho said that in spurning the ICC, the AU was calling “for Africans to be left alone to butcher each other without external interference."

“When all is said and done,” wrote Gaitho, “the AU leaders in Addis Ababa are rebelling against the international court out of self-interest, not higher principles.”

There are other ICC investigations underway, albeit less advanced than the eight African cases.

Chief Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda, the Gambian lawyer who took over from Argentinian Luis Moreno Ocampo in mid-2012, is undertaking preliminary investigations into alleged crimes committed in Afghanistan, Georgia, Colombia, Honduras and Korea. Bensouda has also opened investigations in two more African countries, Guinea and Nigeria.

The ICC was set up as a court of last resort, the place to which victims can turn when all other courts fail — when their judiciaries fail, when their governments fail.

It is little surprise then, that the ICC targets states with weak institutions and long histories of impunity enjoyed by leaders who are so often above domestic laws.

The AU is demanding that the case against their newest member, Kenyatta, who was elected in March, be transferred from The Hague to Kenya. He is accused of masterminding some of the horrific violence that followed the 2007 polls here. Nevertheless, he went on to win the greatest number of votes this year.

The AU claims that sufficient reforms have been enacted to ensure justice is served in Kenya but this is disingenuous. Much-needed and overdue, reforms to Kenya’s judiciary — and other institutions — are underway but not completed, and they have yet to prove themselves trustworthy in the eyes of all Kenyans. If justice for the more than 1,100 dead is to be found, it will only be at the ICC.

The AU’s position puts it firmly back in the camp of impunity. On its 50th anniversary, the AU is once again marching in lockstep with the powerful, arm-in-arm with alleged perpetrators of crimes against humanity, and against Africa’s citizens and victims.

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?