Former Kiribati president eyes massive infrastructure projects to save his island nation

Binata Pinata and her husband Kaibakia walk towards their huts on Bikeman Islet, located off South Tarawa in the central Pacific island nation of Kiribati. Much of the country may be inundated within decades.

The island nation of Kiribati has become a poster child for the existential threat that rising seas pose to low-lying nations.

The country is made up of 33 coral atolls in the Pacific Ocean, most of them less than six feet in elevation.

Some of the country’s 110,000 residents have already had to relocate to higher ground, and scientists warn that large swaths of the country could become uninhabitable in a matter of decades.

The World Bank estimates, for example, that half of the town of Bikenibeu, population roughly 6,500, could be inundated by 2050 by a combination of sea-level rise and storm surge.

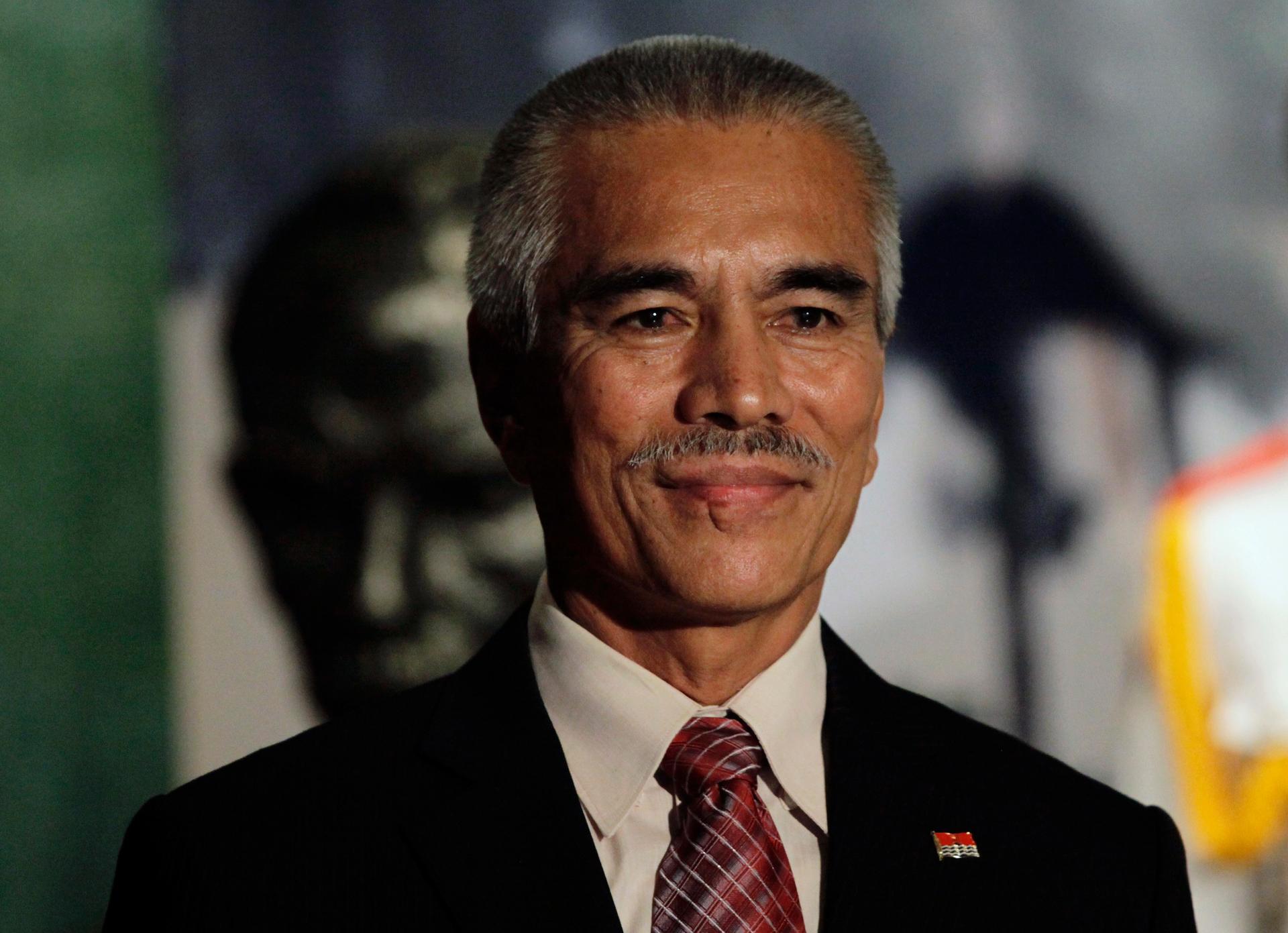

The country's former president, Anote Tong, has long been an outspoken advocate for Kiribati and other low-lying island nations.

And in December of this year, while the international community was deliberating in Paris at the United Nations climate change talks, then-President Tong announced an ambitious plan of his own to help Pacific island nations adapt to rising waters.

It’s called “Pacific Rising” and is being cast as a Marshall Plan for low-lying Pacific nations. Tong said his plan is needed because the Paris climate change agreement to limit global emissions came too late for places like Kiribati.

“The momentum of what’s already in the atmosphere will ensure that we continue to be submerged under the rising seas,” Tong said. “So we had to devise an alternative plan in addition to what’s already there.”

According to the UN, there’s been a reluctance to plan for relocation on the international stage out of a concern that talking about adaption would reduce pressure on big polluters to cut emissions and fight climate change.

But recently, Greg Stone, a scientist with the nonprofit group Conservation International, said money is starting to flow toward vulnerable nations.

“For the first time, nations are stepping up to respond to the commitments they made in Paris to help nations that are suffering from the effects of climate change,” Stone said.

But Stone said there’s no international plan for how to help low-lying nations adapt or relocate.

“No one has a coherent, interdisciplinary approach,” Stone said. “That’s the problem.”

Part of the Pacific Rising plan, which Conservation International backs, is to be a platform to raise funds from foreign governments and private philanthropies for adaptation projects, including infrastructure to preserve drinking water access and disaster preparedness.

Tong said one component of the plan is to work with engineers from the United Arab Emirates, a country famous for its artificial floating islands, to dredge lagoons in Kiribati and deposit sand on the islands to raise their elevation.

Tong acknowledged that the effort is last-ditch and unproven.

“This is why we must do it as soon as possible so we can find out if it will work,” Tong said.

“The technology, the science, the engineering is still in the process of being developed. We cannot develop it without even trying to do it,” Tong said. “I think we should not just give up.”

Tong said he has been talking with governments in the United Arab Emirates, New Zealand and South Korea about adaptation plans, though he provided few details about concrete commitments.

In conversations with foreign leaders, Tong said he stresses the moral question of helping a country like Kiribati, which did little to contribute to climate change but must deal with its most severe impacts.

“What is happening is not of our making,” Tong said. “Really the question, do we leave [people] behind, do we just jump on our own boats and let the rest drown? What would be said about our morality [then]? Where is the justice in that?”

Tong has said his adaptation plan is not meant to be a permanent solution, but a fix that would buy the country more time. While he was president, Tong also bought land in Fiji for relocation.

“Whatever adaptation measures we do are most unlikely to be able to accommodate all of the population,” Tong said, “so we have to think beyond that. So the next alternative would be to relocate people.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story incorrectly identified Greg Stone.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?