Convention drama is hardly an ‘unconventional’ part of US history

Technicians raise balloons to be dropped from the ceiling at the Republican National Convention in Tampa, Florida August 24, 2012.

It’s the final countdown until the Republican Party chooses its candidate for President of the United States and, even with a running mate named, it feels like a lot is still up in the air.

Will the GOP rally behind their divisive frontrunner? Will a dark horse candidate emerge and steal the spotlight? Or will tensions within the party spill into full view? And what about outside protests?

After this week’s maneuvering, it seems unlikely that anything really surprising will happen at the convention, but if any of these scenarios play out, it wouldn’t be the first time. Drama at presidential nominations conventions is hardly uncommon if you look back through history.

Nowadays, it’s rare for the Republican and Democratic national conventions to begin with much uncertainty about who will walk away with the presidential nomination after the stage is cleared and the streamers swept away. Modern conventions are typically in the business of confirming presumptive nominees who’ve emerged from a protracted primary season.

In presidential elections past, however, conventions played a much more pivotal — and dramatic — role in the nomination process.

From 1832 — when Democrats held the first presidential nominating convention in Baltimore, Maryland — until the 1910s, there was no system of primaries, caucuses and delegates. Instead, party elites gathered at conventions and chose nominees on the spot. This resulted in contested conventions that lasted many days and many ballots.

In the lead-up to the 1860 presidential election, for example, the Democrats — who were at that time the party of slavery — were split. Some party leaders believed states should decide whether to keep slavery legal, while others prioritized maintaining slavery’s hold in the American South at all costs.

Party members met in Charleston, South Carolina, for their annual convention.

After casting nearly 60 ballots, they couldn’t decide on a nominee, and delegates from Alabama, Mississippi and South Carolina abandoned the convention in protest. When Stephen A. Douglas — a relative moderate on slavery, who supported the ability of southern states to make slavery illegal — was nominated six weeks later at a second convention in Baltimore, a dissatisfied group of Democrats held a separate convention where they chose their own nominee, effectively splitting the Democratic vote and paving Abraham Lincoln’s path to the White House.

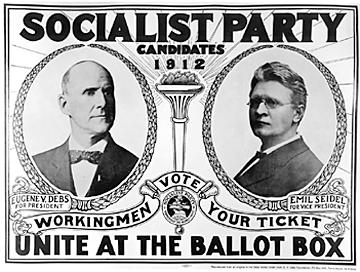

In 1912, primaries as we know them began to play a significant role in determining which candidate would receive each party’s nomination. When former President Theodore Roosevelt decided he wanted to challenge incumbent Howard Taft and launch his own bid for a delayed third term as president, his team hoped emphasizing the voice of the people in state primaries would present an irrefutable argument for his nomination.

[[{“fid”:”105081″,”view_mode”:”image_on_left”,”type”:”media”,”link_text”:null,”field_deltas”:{},”attributes”:{“alt”:”A 1900 campaign poster for William Jennings Bryan features his image and his slogan, \”Equal rights to all, special privileges to none””,”height”:1207,”width”:800,”style”:”font-size: 13.008px; line-height: 1.538em;”,”class”:”media-element file-image-on-left”,”data-delta”:”3″},”fields”:{}}]]Before 1912, Wisconsin was the only state to have a direct primary election. By early 1912, nine other states had primary elections.

Roosevelt and his allies successfully lobbied for Illinois, Maryland and Massachussets to pass primary laws before the 1912 Republican convention. Roosevelt proved wildly popular with an emerging populist movement in the US. But the Republican Party threw its support behind Taft in Chicago on June 7, 1912, causing Roosevelt to break ranks and run with the Progressive Party.

Historian Lewis L. Gould writes in his book “Four Hats in the Ring: The 1912 Election and the Birth of Modern American Politics” that Roosevelt’s abandonment of the Republicans made the 1912 convention “one of the most important conventions in American history.”

Live-wire conventions and division over each party’s political identity in 19th and early 20th century presidential contests made it common for so-called “dark horse” candidates to emerge from the fray and snag the candidacy. Some dark horse candidates — including James K. Polk, Abraham Lincoln and James A. Garfield — rode the momentum that carried them to the top of their party’s ticket all the way to the White House. But several others never even came close to the Oval Office.

[[{“fid”:”105082″,”view_mode”:”image_on_left”,”type”:”media”,”link_text”:null,”field_deltas”:{},”attributes”:{“alt”:”Franklin Delano Roosevelt sits before a curtained window, a microphone on the table, as he prepares to broadcast his first \”fireside chat” from the White House in 1933. “,”height”:768,”width”:605,”style”:”font-size: 13.008px; line-height: 1.538em;”,”class”:”media-element file-image-on-left”,”data-delta”:”4″},”fields”:{}}]]John W. Davis was one of those unsuccessful dark horse candidates. In 1924, the Democratic Party was so divided over who to nominate that their national convention lasted sixteen days. Historian Herbert Eaton reports in his book “Presidential Timber: A History of Nominating Conventions, 1868-1960” that the rift centered around the Ku Klux Klan — one half of the party saw the Klan, which had been gaining renewed influence since its dissolution in the 1870s, as a powerful political ally in the rural South, while the other half viewed its racial and social conservatism as too divisive to associate with.

It took convention attendees 103 rounds of voting before they settled on West Virginian politician and diplomat John W. Davis as their nominee. Davis who would go on to lose in the general election to Calvin Coolidge.

Since the hotly contested Democratic nominating process in 1924, there have only been a handful of contested conventions: in 1932 for the Democrats, and 1940, 1948, and 1952 for the Republicans.

While there was so much talk of contested conventions this year, recent history argues against it.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!