How art and design students think about the future of biotech

The brochure for the Biodesign Challenge.

Art and design students from across the country gathered in New York City last month to participate in the first-ever Biodesign Summit, the culmination of a semester-long challenge to conceptualize a biotech product for the future.

The students took inspiration from the natural world, as well as advancements in technology, to design products that might one day improve our daily lives and ecosystems. Most of the ideas were still in the conceptual phase and need much more research, prototyping, and testing to become viable, but many of the teams were optimistic about the possibilities that lie ahead for their creations. And check out a video about the design challenge, too.

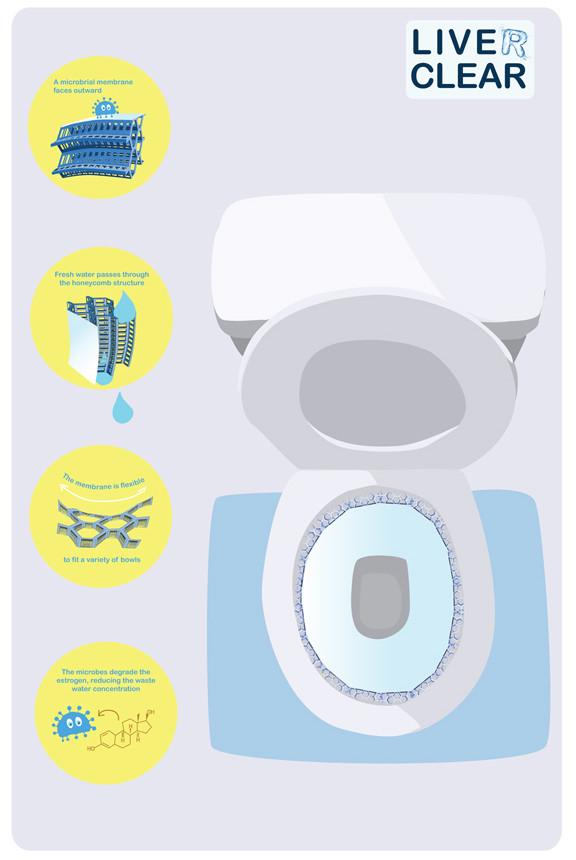

Live(r)Clear

This filtration system, designed by students from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in New York, is aimed at “an invisible but very serious problem—estrogen in wastewater,” the team explained in an email. Through their research, they learned that estrogen from various sources (including natural expulsion from our bodies) wends its way into wastewater.

So the team decided to create a consumer product that lines the common toilet, like “living wallpaper for a toilet bowl, working hard to clean compounds out of your waste that wastewater treatment plants aren’t equipped to handle.” The silicone lining has a microbial membrane that binds to estrogen and draws it into a filter to be broken down.

The team took inspiration from the family of cytochrome P450 enzymes, which, in humans, are found primarily in the liver and metabolize drugs and toxins, as well as estrogens, among other roles.

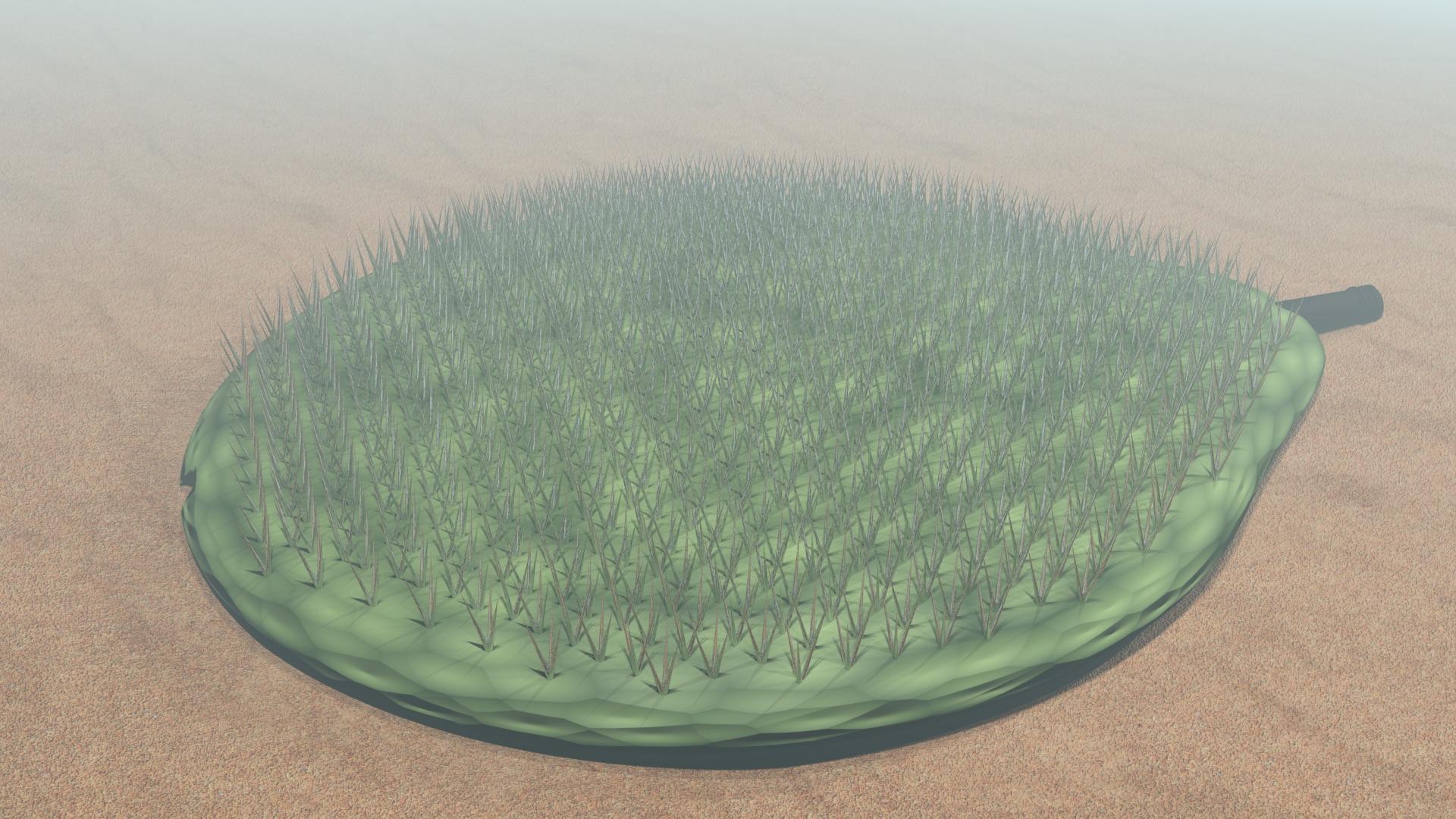

dewpoint

A team of students from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago was inspired by the Opuntia genus of cacti — colloquially known as the prickly pear — and its “unique ability to collect and store water droplets from fog,” they wrote in an email. They designed a set of panels that look like cactus pads, with spines that mimic the conical shape and vertical grooves of real cactus spines that help pull water down from tip to base.

The dewpoint panels also have small openings at the bottom of the spines, like real cacti stomata, that allow water in when open and prevent water loss when closed. The team envisions the panels being installed on roofs and in gardens to collect water as “an efficient and sustainable supplement to our current water supply.”

Check out a video from the challenge, below:

oembed://https%3A//www.youtube.com/watch%3Fv%3Dii_oMviF-b4

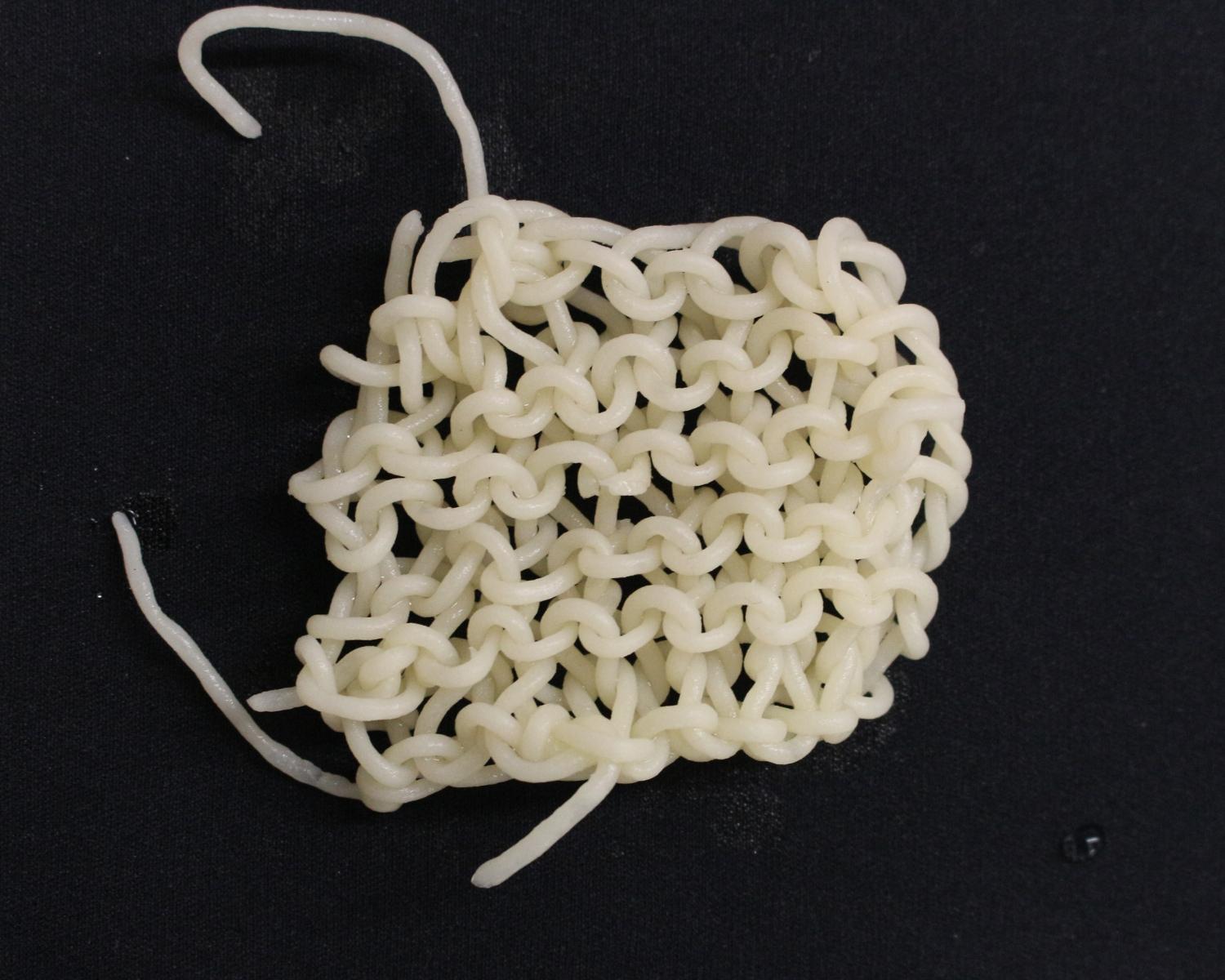

Bioesters

The Bioesters team from the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York City wanted to find a way to reduce the greenhouse gas emissions and toxic waste created during textile manufacturing.

“We see significant improvements in sustainable energy production, but not a lot in sustainable textile and apparel production,” Gian Cui, a member of the group, wrote in an email. They worked with a form of a polysaccharide called alginate, which is found in the cell walls of brown algae (what the group refers to as “low energy-consuming organisms”).

By extruding the alginate into calcium chloride, they created biodegradable filaments that they treated like yarn, knitting them by hand into a textile. With further experimentation, they were able to change the property of the filaments “from stiff and opaque to soft and transparent,” Cui wrote.

The team also printed a mesh made from the same material using a 3-D printer, because “we imagine in the future, most of the manufacturing process will be automated by robots.”

Stabilimentum

The team from the University of Pennsylvania had two motives: to make use of an organism many consider a nuisance, and to employ a material readily found in nature. This came down to the spider and its web.

Upon learning that spider webs exhibit electrostatic properties and can attract small charged particles, they were inspired to create a product in which webs would act as air purifiers.

“We figured that if spider webs are capable of catching pollutants that are present in the air, we could propose them as a natural and biodegradable alternative to wearable air filters, while at the same time creating a new symbiotic relationship between humans and spiders,” the team wrote in an email.

Their concept consists of three components: Two types of wearables designed to be worn over the face or body, consisting of cartridges containing webs that would trap pollen, pollutants, and particulates; and a habitat — placed in a garden or natural setting — in which spiders would build the webs that would be used in the wearables. The team estimated that it would take about a month for 75 spiders to spin enough web for use in more than 30 air purification cartridges.

And, despite what the image suggests, the spiders would stay in the habitat — no spiders in your face!

This story was first published by Science Friday with Ira Flatow.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!

.jpg&w=1920&q=75)