In the future we will be making babies from skin cells, an author predicts

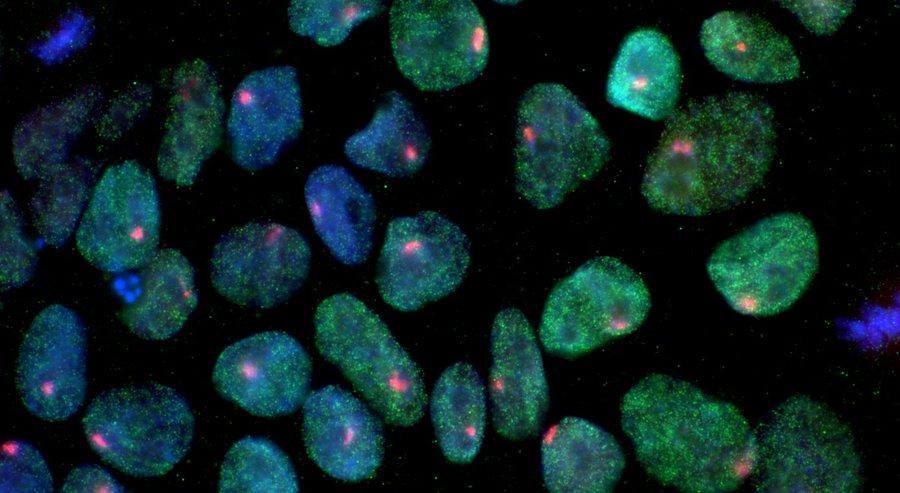

Induced pluripotent stem cells reprogrammed from human skin.

A new book suggests that within just 20 to 40 years, most human reproduction will take place in the lab, rather than the bedroom.

Hank Greely, a Stanford professor who teaches law and genetics, writes about this potential brave new world in, "The End of Sex and the Future of Human Reproduction."

While the book title refers to the “end of sex,” Greely is not predicting the end of human sexuality.

“I think that we will continue to have whatever we and Bill Clinton define as sex enthusiastically for a long time, but I don't think we're going to use it to make babies nearly as often,” Greely explains. “My guess is that in 20 to 40 years, most people in countries with good health systems will conceive their babies in clinics so they can do whole genome sequencing on about a hundred embryos and pick the embryo they like best.”

This is different from so-called designer babies, Greely says. “What I'm talking about is embryo selection. Two people get together and they make embryos. The embryos can only have whatever those two people bring to the plate. If they're both blue-eyed, they're not going to get a brown-eyed baby. If they're both blood type O, they’re not going to get a blood type A baby.”

With designer embryos, on the other hand, one could, in theory, change the actual genes and change the genetic variation, so that people who were blood type O could have a blood type A baby, he says.

What Greely describes is based on the discovery of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), for which Shinya Yamanaka and John B. Gurdon won the 2012 Nobel Prize. iSPCs are cells that are reprogammed to become immature stem cells capable of developing into any type of tissue in the body.

iPSC research has generated great excitement in the scientific community and a lot of money and effort is going into it, Greely says. But it’s not going into it for reproductive purposes. “It’s going into it for nerve cells and pancreas cells and other cells for medical purposes — but as we learn more about deriving specific cell types from these iPSCs, we’re going to make eggs and sperm. … It’s just a matter of time.”

Making eggs this way is focused mainly on eliminating the need for egg harvesting, which is expensive, unpleasant and risky, Greely says. “Sperm harvest has not been as big a problem. But when you do a harvest for IVF, you get somewhere between zero and 25 eggs, Usually about 10 or 12. When you make them from skin cells, you could make hundreds of thousands, potentially millions.”

One hundred embryos seems a more manageable number to work with, Greely says. Each of those 100 embryos would have a combination of the genes from the parents, with different traits and possibility of diseases. Through analyzing the genetics of those embryos, doctors would be able to give parents a choice of good news and bad news. The prospective parents would then face the hard task of trying to weigh all the pluses and minuses.

“I think parents would be asked, ‘What do you want to know,’" Greely predicts. “‘We can tell you about the really nasty early genetic diseases that affect one to two percent of births; we can tell you about risk factors for later diseases like breast cancer, colon cancer, Alzheimer's disease; we can tell you about hair color, skin color, nose shape, early white hair and things like that; we can tell you a little bit about behaviors. … What do you want to know? We'll tell you and then you tell us which embryos you want to move into a womb to try to make a baby.’”

Among the many ethical issues Greely raises in the book is, what’s to prevent someone from getting some skin cells from a celebrity or a movie star and making a baby from them? You just happen to shake hands and rub off some skin cells, so you turn them into an egg and have their baby.

“I think we will need laws against inadvertent parenthood,” Greely says. “Right now, you'd have to steal somebody's eggs or sperm, and that's tricky. But stealing cells from somebody? Any discarded Coke can is going to have some cells on it. The whole issue of being able to make gametes from cells is going to bring up some things that will be surprising, and some I'm sure I haven't thought of.”

This story is based on an interview that aired on PRI's Science Friday with Ira Flatow.