Did you know GPS used to be controversial? Here’s how it survived.

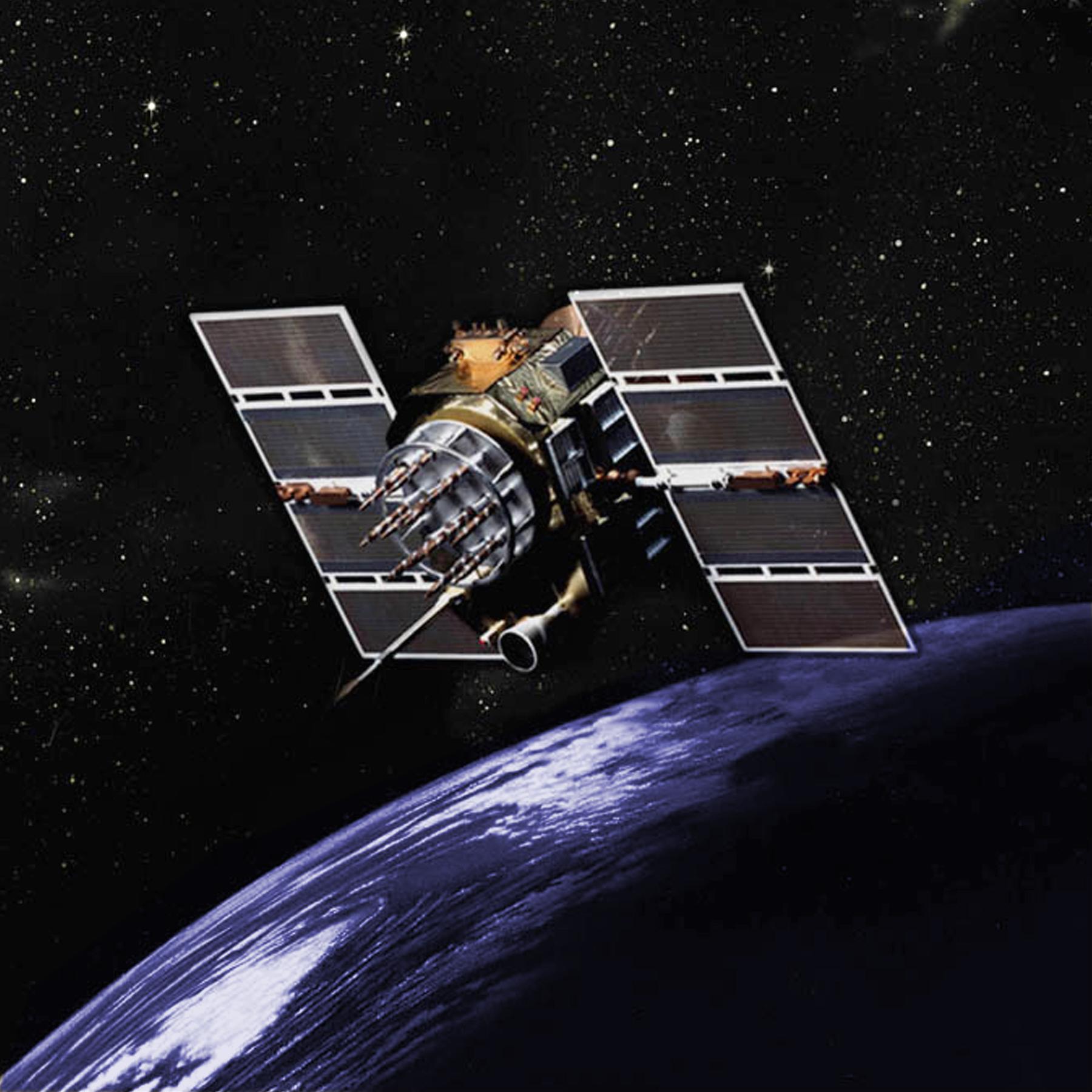

A GPS satellite. Credit: United States Government

In the early 1970s, the idea for a satellite-based modern navigation system was controversial within the United States Air Force. Many in leadership didn’t want anything to do with the project that would become our now-ubiquitous GPS — they thought the money was better spent on putting more planes in the air.

“It was almost guaranteed that it wouldn't go anywhere because it had been floundering for four or five years,” says engineer and former Air Force colonel Bradford Parkinson, who was hired to lead the GPS project back then. “I appreciated what it could do, but unfortunately not only was there skepticism of what it could do, there was skepticism on whether that was where the money should be spent. It was a constant struggle, even after we had reformulated the whole system, to try to get particularly the Air Force to agree that this was what they ought to do.”

Parkinson directed the GPS project during that fragile time, and made countless appeals in Washington to get it approved and keep it approved in the years it took to perfect the technology. He’s now receiving the 2016 Marconi Prize for his dedication to ensuring that the first GPS satellites got off the ground. He credits GPS success to some help he had from people in the US Air Force and office of the Secretary of Defense.

“I was surrounded by some wonderful people,” Parkinson says. “The boss that I worked for, a three-star general, encouraged me to hire the very, very best from within the Air Force … But the other ingredient, which I think was equally important, or perhaps even more important, was that there was a high-ranking civil person in the Office of the Secretary of Defense … who took a personal shine to this program. … He, in essence, said, ‘Air Force, let the young colonel go off and build the system.’ He told them, ‘Just wait and see. He’s going to do it.’”

Some people say GPS was originally a military system that was eventually made a civil system.

“That’s not true,” Parkinson says. “When I testified before Congress back about 1975, I said this is a combination military-civil system. We originally thought the civils wouldn't get quite the military accuracy but it turns out there are a lot of creative people out there and in no time at all they got close to the military accuracy.

"Briefly the military tried to mess that up but then realized there was no point in it."

Now Parkinson is concentrating all his time on making sure GPS is as resistant as possible to attacks such as jamming, which could be used as a weapon to disrupt everything from air traffic to the stock market.

“There is a lot at stake,” Parkinson says. “I've devoted most of my recent life to ideas on how one toughens a GPS receiver and for safety or economic critical applications we know how to make it very very jam resistant. But unfortunately those ideas have not been deployed yet. There is another threat. I should add that the FCC is contemplating putting very high-powered broadband transmitters in the adjacent band and if that were to happen, the chances are a lot of users who rely on it now are going to be taken out.”

This article is based on an interview that aired on PRI's Science Friday.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!