Activists from around the world describe waging non-violent campaigns

Maryam Al-Khawaja

Maryam Al-Khawaja is a human rights activist from Bahrain who is the Co-Director of the Gulf Center for Human Rights. She was involved in the protest movement in Bahrain in 2011, and advocates for human rights defenders in the region. Al-Khawaja’s father is also a human rights activist and was imprisoned in Bahrain for his work. Al-Khawaja went back to visit her father in prison in 2014, and tells the story of what happened.

“I was going back to Bahrain in 2014 to visit my father. He was on hunger strike and we didn't know if he would — he was at risk of losing his life at any time because of the hunger strike so I decided to go home to see him. I was arrested upon arrival in Bahrain. I was assaulted by the police. They damaged my shoulder muscle and then the same police officers who had assaulted me accused me of assaulting them, even though I told them that even if they beat me I will not respond because I'm a non-violent activist. When I was assaulted, I did not fight back.

“After that I was imprisoned for three weeks and I was charged with assaulting police. I have five other pending cases, but because of international pressure it became more costly for the Bahraini government to keep me in prison rather than to release me, so they released me. They allowed me to leave the country and then I was sentenced to one year in absentia. I'm currently wanted in Bahrain, and like I said I have five other pending cases as well. If I ever do go back to Bahrain, I doubt that I would be getting out any time soon.”

Al-Khawaja says that though her work in Bahrain and other Gulf countries has led to more arrests and violence, working peacefully for human rights is worth it in the long run.

“I would say as someone who has lived in a country where you don't have dignity, where you're not speaking out, where you're not taking to the streets, I see living in that situation is actually worse than deciding to come out and fight for those rights, even if it ends up costing you your freedom or your life at some times. I think that it really, from the outside, yes, it might look worse because the number of people getting arrested and tortured and killed is definitely much larger, but the fact that people took to the streets to demand their fundamental and basic human rights and freedoms, I think is something that should be applauded. It's something that actually changes something in the society, because dignity is something that they can no longer take away from us, it's something that we've regained and they can't take away again.”

Emily Bailey is an environmental activist from Wellington, New Zealand. She is part of a group called Climate Justice Taranaki (the name of the province where she lives) that works on climate change issues, sustainability and stopping fossil fuel extraction and use.

“Taranaki was the first place where people drilled for oil and there's still oil and gas production here. There's hundreds maybe thousands of wells across the region. In recent years with the rise of fracking there was a mass expansion of oil and gas in this region so our group formed to try to combat that.”

Emily has also worked with a small Māori community in Taranaki called Parihaka, which has a long history of peaceful resistance dating back to the British rule in the 1800s. She says that’s where she learned about nonviolent protest.

“I've been an activist for I don't know 10, 20 years or something now. When I first started it was amongst anarchist and environmentalist who were quite young and passionate and angry about the world. I guess our way of activism then was very, kind of, in your face and sort of protest protest and shout at people and come up with not very nice slogans. Fair enough, there were people who were doing really bad things. But we lost and we lost and we lost. It just didn't work. I guess in recent times through being at Parihaka, I've learned different ways of doing it. Just through things like forming relationships with people where you can actually start to talk and explain your point of view then they actually listen. Using the media trying to explain what you think and why and putting it into stories in the paper and TV so people understand.”

Bailey says the people of Parihaka used such methods to prevent the expansion of the oil and gas industry in their community.

“We put a letter together, the whole community wrote this letter, and we sent that to all the companies, to the counsels, the government, the UN, some other industries — I think the unions — and said, 'look, we don't like what's happening. We don't want you to do it. It's hurting our land, it's hurting the atmosphere it's hurting our people. Please stop.' We didn't hear anything back.

“And then about a year later we got the new oil and gas permit block maps and suddenly there was a square around us. They'd taken us off the map, which was great. That was a good thing. They are no longer going to drill around us. It just showing that just by talking — I guess just by saying what we think and why — that we're going to stand in their way if we have to. They backed off.”

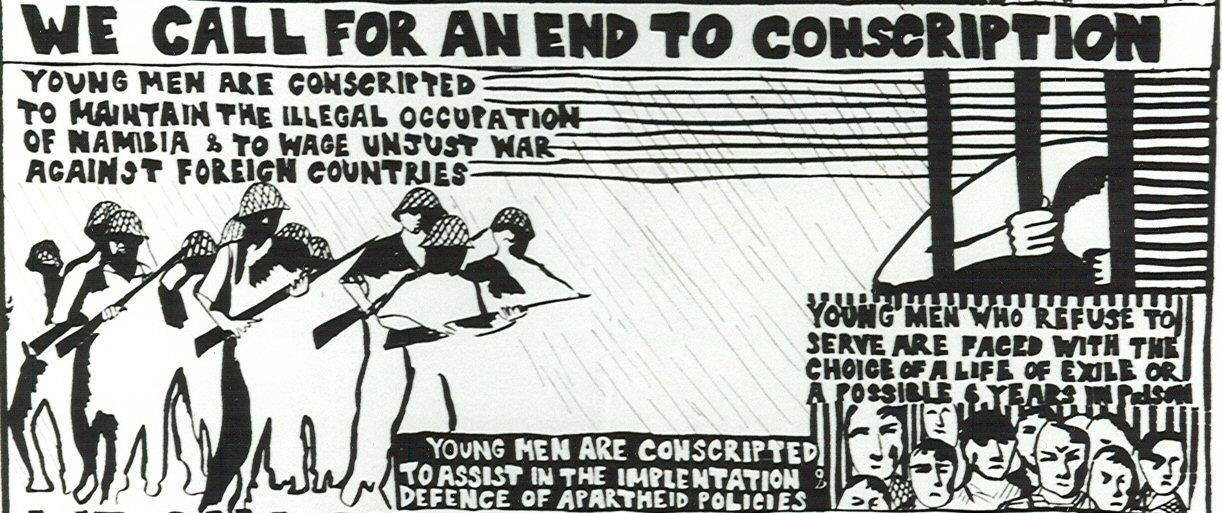

Jonathan Ancer was a member of the National Union of South African Students, which was an anti-apartheid organization. He was also active in an organization called the End Conscription Campaign, which opposed military conscription. White South African men were conscripted into the South African Defense Force and the organization fought against conscription into the apartheid's army.

“Well, I think as an organization, it probably can't claim to have played a role in dismantling apartheid, but I think it played its part in the sense that it conscientize a lot of white people to what was going on in South Africa, what was really going on. People led a very sheltered life about what was happening in their own country, and I think the End Conscription Campaign also gave a really big finger to the apartheid government in saying, ‘You know, we are white people, and we don't agree with what you're doing,’ and I think that in itself was quite a powerful statement.

“The one amazing thing about this organization, it was a single-issue organization, so it campaigned around one specific issue, which was the ending of conscription into an apartheid army. And it brought together a whole lot of people. They were hippies and Marxists and members of the ANC (African National Congress) and pacifists and Christians and Jehovah's Witnesses. They were just a range of people who all came together for one specific issue, and that was to oppose conscription into the South African Defense Force. I think that, you know, was a powerful statement.”

Because he reached draft age in 1989, Ancer's involvement in the anti-conscription movement coincided with the fall of apartheid in South Africa.

“Being involved at that time was quite a special time. It was right at the death of apartheid, and there was a feeling of magic in the air that something big was happening and that we were part of it, and we were all embracing each other. South Africa today is in a very different space, but at that time there was a really amazing feeling that we were making history.

“That was a very special time to be an activist in South Africa, and I felt that I was really important. In the grand scheme of things I was very unimportant, but it felt that we were changing the world and we were changing lives. Maybe in a very tiny way we were, but it felt that we were part of something huge.”

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!