Thanks to librarians, Timbuktu’s cultural heritage was saved from extremists

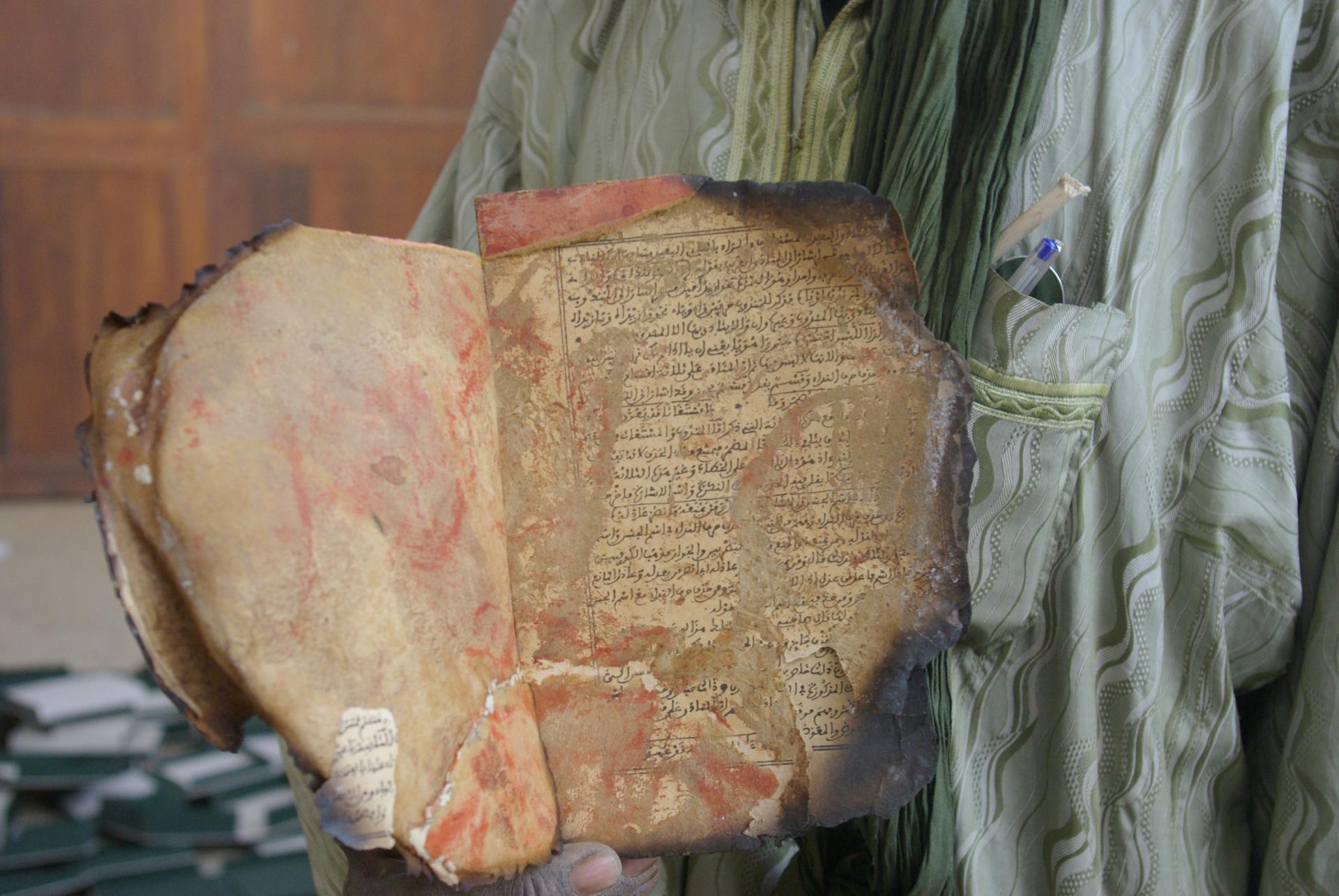

With the armed conflict that occurred between 2012 and 2013, Mali's cultural heritage, including its ancient manuscripts, was severely damaged. In Timbuktu, many valuable manuscripts were burned or stolen, forcing their owners, communities and local NGOs to send them to Bamako, the capital of the country, in the most precarious conditions.

Perched on the Niger River, Timbuktu was once a major stop on trade routes across North Africa and a coveted destination for scholars nearly 600 years ago.

“Mali, in that era — the golden era of the 15th and 16th centuries — was the center of a great North African empire, and Timbuktu was the cultural, economic and intellectual capital of that empire,” says author Joshua Hammer.

Writing mostly in Arabic, the scholars that visited Timbuktu studied astronomy, medicine, poetry, and music and debated the details of Islamic law.

“Books were produced there — manuscripts — at a huge rate, and then over the centuries were scattered,” Hammer says. “The French colonial army invaded and conquered the north of Mali in the 19th century, and began seizing manuscripts where they could find them, taking them to museums in Paris and libraries in Paris.”

The people of Mali didn’t want to part with these precious treasures, so they hid away these prized manuscripts, and many were forgotten for decades.

But about 15 years ago, thanks to international funding from UNESCO and the efforts of Abdel Kader Haidara, a young man from the city, hundreds of thousands of these manuscripts were brought back to Timbuktu and preserved by teams of librarians in newly built facilities.

As a young man, Haidara scoured the country, traveling on camel and by boat to convince the owners of these manuscripts to entrust them to him in exchange for livestock and cash. The librarian wanted to ensure these invaluable volumes, some of which were buried in the desert, would last for hundreds more years.

But trouble was coming to Timbuktu.

In 2011, the fall of Colonel Muammar el-Qaddafi in Libya prompted a flow of arms across the desert, and preachers of Wahhabism from Saudi Arabia set up shop in a new mosque in Timbuktu. Then, in 2012, an unlikely coalition of Tuareg nationalists and Islamic extremists took over the city and threatened to destroy these priceless manuscripts

But many brave men and women in Timbuktu were able to save 375,000 precious manuscripts from destruction, something Hammer chronicles in his book, "The Bad-Ass Librarians of Timbuktu."

“It was an enormously complicated operation that had several stages,” he says. “The first stage was taking them in the middle of the night by flashlight out of these libraries, and stashing them inside private houses, where they remained for several months.”

When extremists moved to occupy Timbuktu four years ago, they imposed Sharia law and doled out cruel punishments on those that resisted — public executions were carried out regularly, individuals were stoned to death, and suspected adulterers were mutilated in public squares.

But that didn’t stop Haidara or those working with him — they moved forward with a plan to save these coveted texts, and risked their lives in the process.

“The next step was to actually get [the manuscripts] out of the safehouses in Timbuktu and smuggle them past jihadi checkpoints and down to Bamako, the capital of Mali,” says Hammer. “The third and final stage came when the French military invaded, and the whole north became a warzone — you could no longer travel on the roads. At that point, [Haidara] had to switch gears entirely.”

Haidara relocated his operation further down the Niger River. In the end, this group of “bad-ass librarians,” as Hammer calls them, were able to save all but 4,000 manuscripts.

“Those 4,000 were left behind in a library that had been occupied early on by the jihadist and turned into a military barracks,” Hammer says. “They had been coexisting with these volumes — doing their military training and not bothering with them, strangely enough. And then in the last days, as the French were about to seize Timbuktu, in a spasm of vengeance, they grabbed everything that they could find and made a big pyre, doused it with gasoline, set them on fire, and destroyed everything and reduced them to ashes.”

Though the country has a high illiteracy rate, there's wide support for preserving the texts/ the importance of preserving the texts is widely understood.

“There is still, even among people who can’t read, a recognition of the specialness of Mali — that this very poor country was once at the center of this great intellectual and economic empire,” says Hammer. “These books are seen as vestiges of that.”

While these texts have been saved, Mali still hasn’t recovered from this violent period.

“[It’s] one of the most traumatic episodes in its history,” says Hammer. “The French came in 2013, and they were effective — they killed a large number of jihadis; they drove them out of the cities. But the desert is still there, and there are jihadis still around — they’ve already conducted a few horrific terrorist operations in Bamako and elsewhere. I don’t think they’re capable of recapturing the north, but the instability is likely to go on for a long time.”

This story first aired as an interview on PRI's The Takeaway, a public radio program that invites you to be part of the American conversation.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!