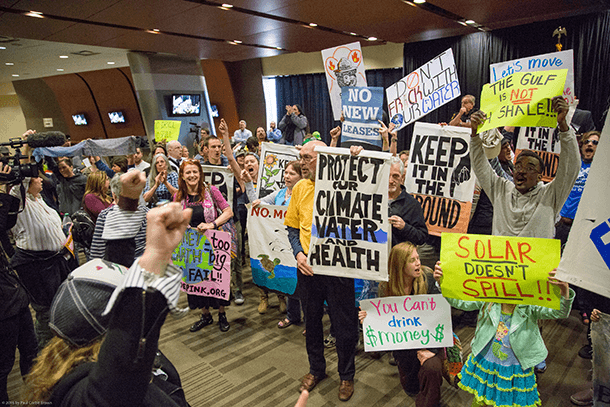

Louisianans rally against new Gulf oil leases

Protesters rally at the Superdome against new oil and gas leases.

Louisiana has long been a friendly state to the oil and gas industry, but a movement is building against the effects of drilling in the region.

Hundreds of people recently rallied at the Superdome in New Orleans to protest the sale of new federal leases for oil and gas extraction in the Gulf of Mexico. Anne Rolfes, of the environmental justice group Louisiana Bucket Brigade, says the rally represents a major shift in public attitudes toward Big Oil.

“The pushback [here] has always been around mitigating the harms,” Rolfes explains. “You know, ‘Please, Oil Industry would you stop polluting? Please, Oil Industry, would you stop expanding? Please, Oil Industry, would you stop your accidents?’ They've never cooperated with those requests and so we've changed. Now we’re saying: ‘Oil industry, we're not asking anymore; we’re telling you not to drill and we're going to make sure that happens. No new drilling. Our days of supplication are over.’”

The protesters gained access to the Superdome, where the lease auction was held, and basically took over the room, Rolfes says. “We went into the front, we stood on the podium. The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management was still at the microphone, but they could not be heard over our din and we had a pretty basic message, which was ‘the Gulf is not for sale.’”

Even so, the auction was successful. Rolfes says the bureau's spin was, “What protest?”

“They honestly acted as if it didn't happen,” Rolfes says. “I imagine that's strategic, to try and deter us from such actions in the future. But by any measure, this is a different day and those of us who participated in this understand that, and understand that this is only the beginning.”

In fact, the BOEM did take notice of the protest. Shortly afterward, the bureau rescheduled a series of public meetings in order to "accommodate a larger than anticipated number of attendees."

The public mood has shifted in large part because the oil industry is “acting like it's still the 1980s,” Rolfes says. “They’re saying the same things they were saying then, pretending like they don't have a problem with accidents, pretending like their spills don't cause harm.”

In reality, the industry has done grave harm to the region’s wetlands, even according to its own studies. The industry claims responsibility for at least a third of the wetland loss, while other accounts put that figure as high as 75 or 80 percent.

“The result has been that they physically dug out our land, which was our protection from storms,” Rolfes explains. “One of the reasons that Katrina was so devastating was because of that wetland loss. The oil industry’s destruction of our coast makes us more vulnerable to every single hurricane that comes through.”

Ironically, even while the oil industry acknowledges this, their own reports include visual renderings of the state as it looked around the year 1970, Rolfes notes, “as if we have all of our wetlands, as if our state is really a boot like it used to be, when really that boot has eroded."

Rolfes says that even until quite recently, the prevalent attitude in Louisiana was, ‘What can you do? It's Big Oil. There’s no way we can stand up to that.’ That, too, seems to be changing.

Citizens who oppose more drilling in the Gulf feel that they have more power than in the past. A network of local, regional and national groups and individuals participated in the protest.

“This is one of the rare times when our interests are perfectly aligned,” Rolfes says. “We have the same agenda, we're part of a movement, and that's why I always have faith. I always have faith.”

This article is based on an interview that aired on PRI’s Living on Earth with Steve Curwood.