The walls in Van Gogh’s iconic ‘The Bedroom’ were never meant to be blue

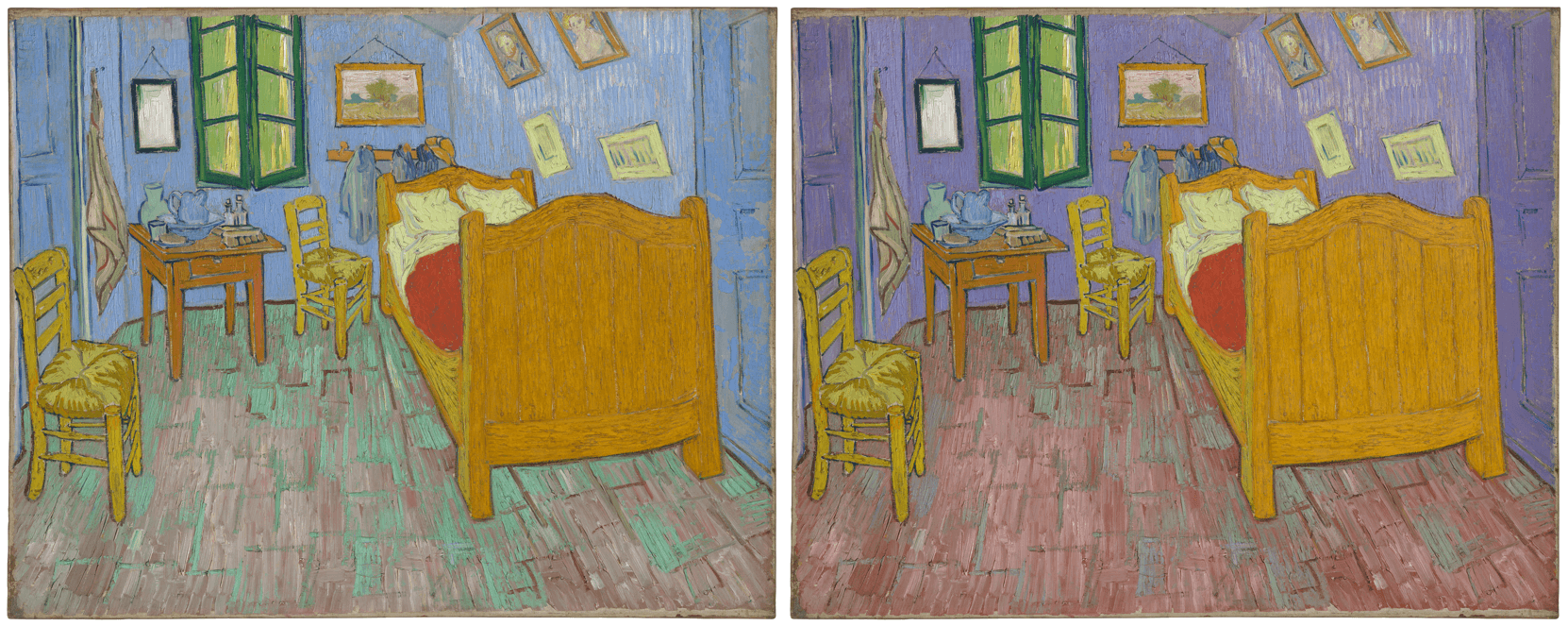

On the left, The Bedroom as seen in real life. On the right, a digital recolorized visualization.

The Art Institute of Chicago recently made a surprising discovery about Van Gogh’s iconic painting, “The Bedroom.” The walls in the room, which look blue to us now, were actually purple when Van Gogh originally painted them.

“The first clue was actually given to us not by our curator … but by Van Gogh himself,” says Francesca Casadio, senior conservation scientist at the Art Institute of Chicago.

In a 1888 letter to his brother Theo, Vincent Van Gogh described “The Bedroom”: “The walls are of a pale violet,” he wrote. “The floor — is of red tiles.” When you look at the paintings today — there are three paintings Van Gogh did of “The Bedroom” — the walls and doors are no longer a pale violet. Instead, they look blue. And the floor doesn’t appear red, it looks more green and brown.

“In the past 10 years, we've become more attuned to the fact that these pigments can change,” Casadio says. “We now can measure the change and we can identify those fading pigments. We immediately set out to try to answer these questions. … It was a wonderful detective-type work that we were allowed to do on this iconic masterpiece.”

Casadio and her colleagues first began to analyze the painting using new technology borrowed from space.

“We used a gun-like instrument that emits x-rays,” Casadio says. “It's a way of getting information about the pigments without having to touch the surface or remove even the smallest amount of material. And actually this technology was developed to go on the Mars Rover originally to do exploration in space. And we can use it for arts because it basically … allows us to identify the atoms that make these pigments.”

After x-raying the painting, they also performed minor surgery on the masterpiece.

“We used scalpels, like surgical scalpels and a microscope with a very steady hand — you don't want to have had too much caffeine that day. We removed a sample that is no bigger than a dot on a printed page and … mounted this fragment on a microscope slide,” Casadio says.

Under the microscope, they finally solved their mystery: “We were all huddling around the microscope because when you looked at the surface of the sample it was light blue, but when she flipped it over, exposing the bottom part of this painted layer, which had not been exposed to light, it was purple. And you could see all these pink particles that had been preserved because they had not been directly exposed to light.”

Now Van Gogh’s three copies of his painting are hanging together in one room in The Chicago Institute of Art along with an immersive digital experience meant to give visitors a sense of the physicality of Van Gogh’s brushstrokes, and a video explaining the exploration that went into discovering the original shade of the painting.

“It's really very very exciting,” Casadio says. “It's really the opportunity of a lifetime. … I don't think that for the next two centuries this will be possible … [everyone who] will come to Chicago is … able to see the three bedroom paintings all together.”

This article is based on an interview that aired on PRI's Science Friday.