Elaine Marques, 29 (center left) smiles at Germana Soares, 24, at a group birthday party for babies born with microcephaly in Recife, Brazil.

One evening last March, infectious disease specialist Dr. Carlos Brito picked up his phone and sent a message to a group of his colleagues. He’d been seeing patients with a rash, swollen joints and a slight fever — symptoms that were similar to the dengue outbreak he had recently been treating, but different enough that further investigation might be merited, he wrote.

Later that month, a doctor working two states to the north wrote the group that he had been doing some research. “I think it’s Zika,” Dr. Kleber Luz posited. Brito was at a family dinner when he got Luz’s text. He Googled papers about Zika as he ate. By the end of the meal, he put down his phone and told his wife: “OK. I agree with Kleber. It’s Zika.”

Brito and his colleagues weren’t texting each other, they were communicating via the free peer-to-peer messaging platform WhatsApp. In Brazil, where cell phone plans are expensive, WhatsApp has played an outsized role in both the investigation of and response to the mysterious outbreaks of Zika and microcephaly.

Brazil is a heavily connected culture. WhatsApp is the most downloaded app on Brazilian smartphones — an estimated half of all Brazilians use its text and voice messaging regularly — and its ubiquity has proved a boon to doctors and patients communicating about the crises. But it has also created a conundrum for public health officials, who have no way of intercepting the information — and potential misinformation — being exchanged.

The early detective work to identify Zika might have been slower had it not been for the instant exchange on Brito’s WhatsApp group. The doctors in the group met on a professional trip to investigate a chikungunya outbreak in Feira de Santana, Bahia. They formed a WhatsApp group dubbed “CHIKV: The Mission” to keep in touch. They chatted regularly, despite being spread around the country, which allowed them to collaboratively unravel the Zika mystery.

They weren’t the only group of doctors puzzling things out over WhatsApp. In August, doctors in northwestern Brazil began discussing the unusual number of infants they were seeing with a defect called microcephaly, a condition usually accompanied by dire developmental delays. Dr. Isabel Oliveira, an endocrinologist, first heard about the microcephaly cases in August through chatter among her network of doctors; she took special note because she had just gotten pregnant. Dr. Vanessa Van der Linden Mota, a pediatric neurologist in Recife, said she swapped notes and CT scans over WhatsApp with her brother, a neurologist in a city more than 1,000 miles away.

But the phenomenon that made possible the quick exchange of information between doctors does not seem to have sped up a public health response.

“The doctors say they started to notice more cases in August, but it was only reported to us around Oct. 15,” said Patricia Ismael de Carvalho, general director of information and strategic actions in epidemiological surveillance for the Pernambuco State Secretariat of Health.

This highlights a limitation of peer-to-peer networks: Information is still siloed, said Sonia Shah, science journalist and author of the book "Pandemic: Tracking Contagions from Cholera to Ebola and Beyond."

“If you’re an obstetrician, you’re talking to other obstetricians in your network, but you’re not talking to the Ministry of Health,” she said. “You’re not going to text someone unless you know them personally and you know their phone number.”

Unlike Facebook, Twitter and other social networks, WhatsApp is impossible to monitor, because it lacks either a gatekeeper or a search function, said Fabro Steibel, a director of the Institute of Technology and Society, based in Rio de Janeiro.

From information to care

Health officials are trying to find ways through these challenges, Steibel said, because “if you don’t put good information out there, it will only be used to spread misleading information.”

The communications staffs of Brazilian health organizations now routinely release succinct, eye-catching content easily shared on WhatsApp. One colorful slide released by Recife’s Secretariat of Health describes the different symptoms of dengue, chikungunya and Zika. One promoted by Pernambuco’s health department features a giant Aedes aegypti mosquito, advising residents how to avoid it.

To spread these images, Pernambuco’s health department sends them out to WhatsApp groups of its employees and other health professionals, encouraging them to distribute to their own networks, according to a spokesman.

Twenty-seven-year-old Camila Clarissa Chagas benefited from one such campaign last year, after she and everyone in her family came down with a mysterious rash and light fever in March. At that point, Zika hadn’t even been pinpointed by doctors. “The doctor told me he didn’t know what it was — that it was an unexpected virus that had suddenly appeared,” she said.

Then in May, a colleague sent her a WhatsApp message, attaching an image listing the symptoms of the new disease, which had just been identified as Zika. “I think that’s what you had,” she told Chagas.

Mothers united

oembed://https%3A//www.youtube.com/watch%3Fv%3DmEDRufZoDsw%26feature%3Dyoutu.be

In Brazil’s Zika outbreak, WhatsApp has also been connecting patients who might otherwise be isolated.

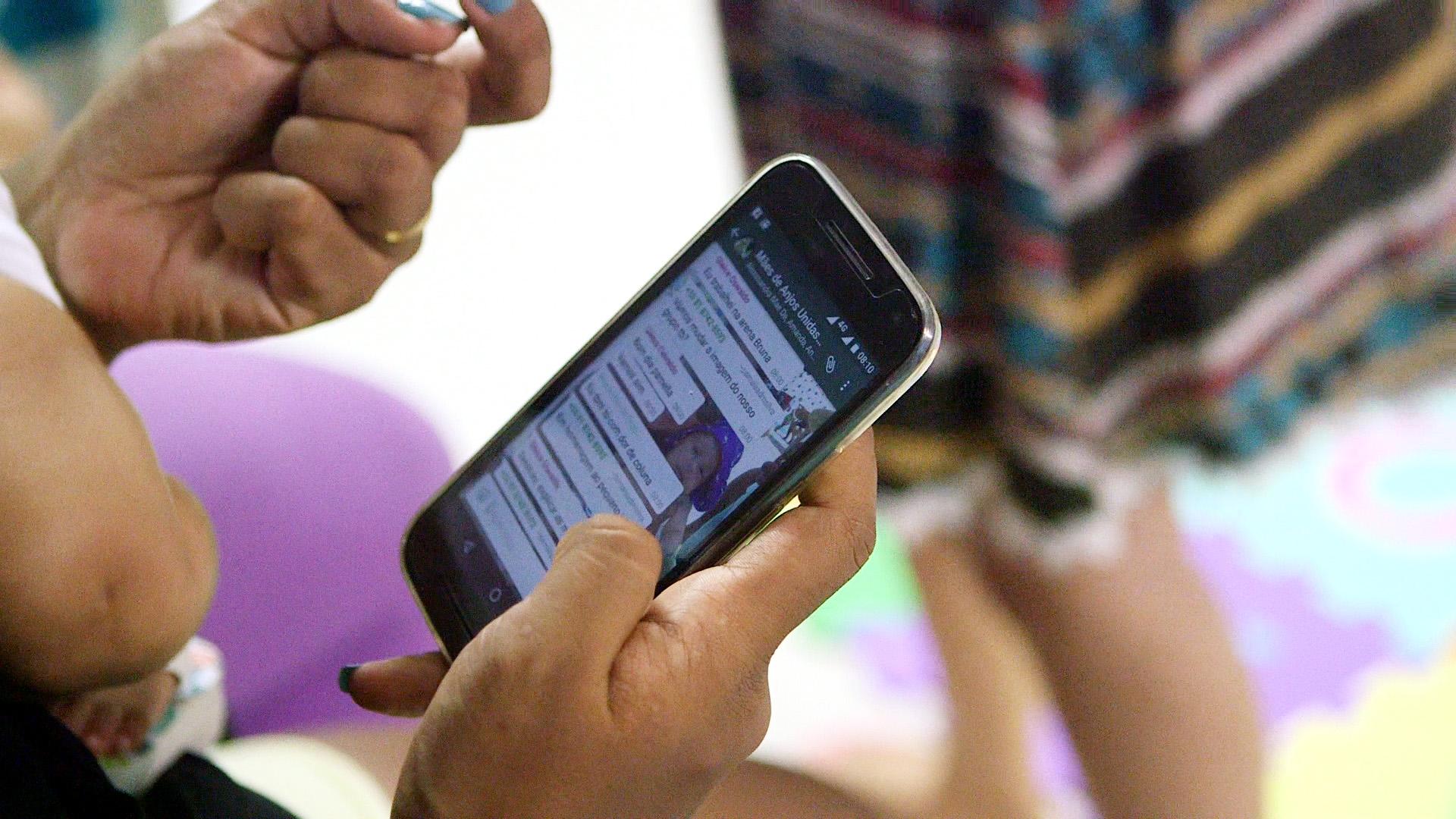

Last week in Recife, office administrator Germana Soares and accounting student Bruna Thamires organized several dozen mothers for a party inside a rehab clinic with their babies, all of whom have suspected or confirmed microcephaly. In the Recife area, more than 60 of these mothers are constantly talking on a giant WhatsApp group chat, where Soares said arranging the party felt natural.

Soares is also part of a WhatsApp group of mothers with microcephaly babies across the country, from southern Rio Grande do Sul state to northwestern Acre.

“These groups allow us to celebrate motherhood at a time we feel faced with lots of stigma,” Soares said.

Psychologist Lucy Jane Lobo, who works at the Altino Ventura rehab center where Soares and Thamires’s sons go for physical, occupational, visual and audio therapy, said that she has observed that mothers who are part of support networks like the WhatsApp groups are facing their circumstances with more resilience. “A more empowered mother is going to take better care of her child and learn more,” she said.

Receptionist Daniele Santos, who is part of the Pernambuco group of mothers, said that even though doctors had told the microcephaly mothers to give their children extra anti-fever medicine before their routine 2-month-old vaccinations, “many mothers didn’t, and they started seeing convulsions in the children. After they told the WhatsApp group about this, and other mothers responded saying how much the medicine helped, fewer people skip the medicine now.”

Gynecologist Glaucius Nascimento was invited by a patient to be a member of the Pernambuco mothers’ WhatsApp group. Nascimento said that so far he has not seen any inaccurate medical information being spread via the chat. He said the group has opened his eyes about the delays the mothers face in booking appointments and getting exam results — and also their difficulty in affording diapers and proper nutrition. This access to his patients’ dialogue has made him question whether his colleagues in the medical field are focused on the right things.

“I’m disappointed in how focused researchers are at identifying whether Zika caused all of this at the expense of focusing on other risk factors that affect these mothers, like whether they were getting enough vitamins and their broader socioeconomic background,” he said.

Not all of the mothers who’ve recently given birth to children with microcephaly are part of the group chat. Smartphones are expensive, and many families in Brazil are too poor to own one. Doctors at the Altino Ventura rehab center recently made a change in the children’s therapy schedules so that parents would come in on the same day each week and have face-to-face contact.

At last week’s party, a few tired babies snoozed on a bed, while others were rocked by their mothers to birthday songs. Some of their mothers are in the WhatsApp groups, others are not. “We’re all in the same boat,” said Germana Soares. “And the boat is full.”

This story was co-reported with our partners at Frontline. Find more on the Zika outbreak from Frontline here.