The trolls are winning. GamerGate case will not go to trial.

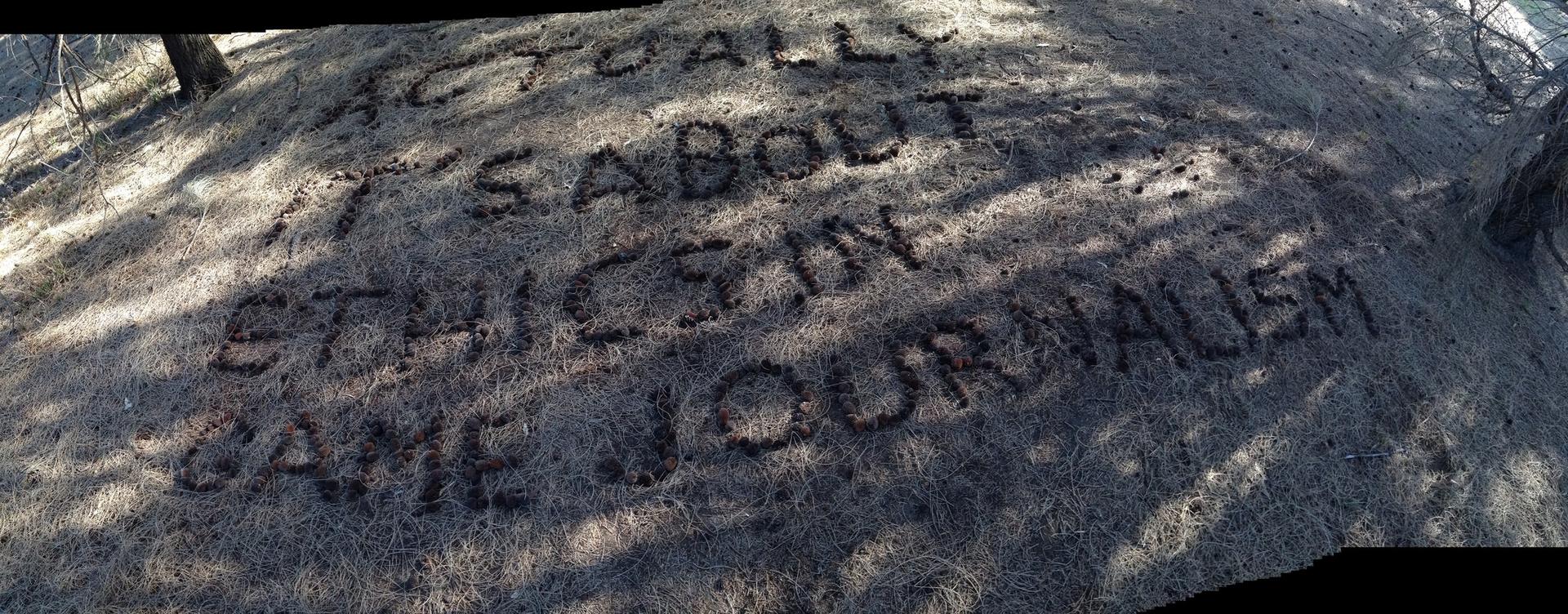

"Actually it's about ethics in game journalism," reads a sign in Melbourne, Australia. GamerGate is a controversy about sexism in online gaming, but opponents claim it's about debunking a female journalist's unethical reporting.

In the battle over online harassment, it looks like the trolls are winning.

In the summer of 2014, Zoe Quinn, an online game developer and reviewer, went through a breakup with her boyfriend. He retaliated by publishing intimate details about her online. Mobs of Internet users got involved and started to harass and threaten Quinn in an affair that has become known as "GamerGate."

Last year, Quinn filed a lawsuit to prevent her ex from commenting on the controversy and stirring up more harassment against her. But this week, she asked the Massachusetts district attorney to withdraw the criminal case.

“I don't think the courts are ready to deal with this quite frankly,” Quinn told The Washington Post.

But Quinn’s experience is not unique. Brianna Wu, a game developer, journalist, and podcaster, was forced to leave her home in October 2014 after harassers published her address and made threats against her online.

“Zoe is kind of the spark that started this in the public consciousness, but she’s also part of a trend that had been happening to women in the gaming industry throughout most of 2014,” Wu says. “I had been speaking out and seeing some of my friends targeted, and eventually they went after me as well.”

In the last year and a half, Wu, CEO of the game development studio Giant Spacekat, says she has received more than 200 death threats, adding that she gets rape threats “constantly.” However, she feels that the larger GamerGate movement goes beyond individuals, arguing that it is connected to the role of women in gaming.

“I think the average person can look at video games and understand that we have some extreme problems in the way that we represent women,” Wu says. “What has happened is, for the last 30 years, video games are perceived by a certain portion of gamers to be their club house. Now that the video game industry is changing, and we have a lot more women developers, women journalists, and women CEOs like me, that is very, very threatening to a certain portion of gamers.”

She adds: “Our crime is simply being a woman in this field and speaking to our lived experience, and asking the industry to do better.”

While most states have passed legislation to prevent cyber harassment, Danielle Citron, a professor of law at the University of Maryland, says the law often breaks down and fails to protect targets of online harassment.

“If you’re going to be convicted of harassment, the state’s got to prove that someone intentionally, repeatedly, [and] persistently targeted the person with speech that we can punish,” says Citron. “Some of the problem when you have a huge collective of people targeting a specific person is that it may be that any given person in the mob may contribute a little to the abuse, but not one person is responsible for persistent, targeted abuse.”

Taken together, a wave of online harassment from many different people can be intimidating and threatening. Yet, it presents a huge barrier for law enforcement looking to bring charges against any one individual.

“The law has great potential here, but as we’ve seen it’s a blunt instrument — sometimes it fails us,” says Citron. “What we saw in Zoe’s case, she gave up because it just became too much for her and her loved ones to bare.”

Citron, author of the book “Hate Crimes in Cyberspace,” says part of the problem lies in education. Many police officers and other law enforcement officials do not know how to investigate cyber harassment, or recognize the scale of the problem. Between 2010 and 2013, for example, about 2.5 million cases of cyberstalking occurred, yet federal prosecutors pursued just 10 cases.

“They need a lot of training to understand the real significance of this kind of behavior and its real world impact,” Citron. “That really presents problems, not only if you have all the evidence and you can trace all of the posts to specific individuals, even if they all are engaging in prescribable conduct like a true threat, it may be that law enforcement feels outgunned.”

In addition to education, Citron says that social attitudes among law enforcement officials is also a problem.

“In my book, I document how law enforcement will tell victims, ‘Eh, turn your computer off,’ [or] ‘Boys will be boys — it’s no big deal,’” she says. “I think we’re making a little bit — I’ll say very modest progress. We’ve seen top cops like [California Attorney General] Kamala Harris take on this issue, and really think hard about ways in which law enforcement can be better trained.”