How one school is using hands-on and high-energy learning to help its low-income students succeed

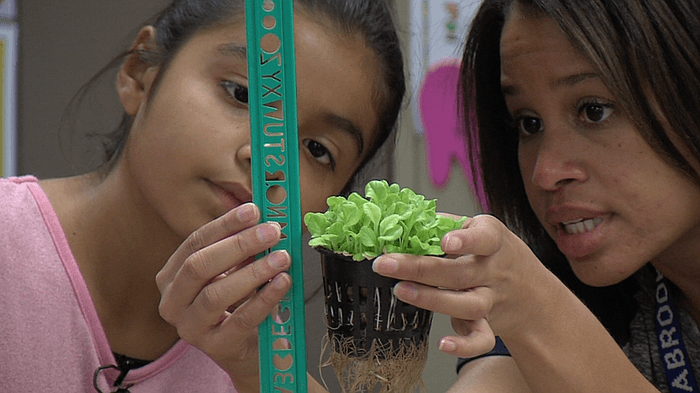

Third grade students learn to grow plants without soil at the Casita Center For Technology, Science and Math in Vista, Calif.

Elena Gomez, 9, is the meteorologist on a live televised newscast at her magnet elementary school in Vista.

“I’ve learned that I have to speak up because otherwise people who are watching the video will not hear me at all,” says the student of the Casita Center for Technology, Science and Math.

Gomez speaks English as a second language. Her Mexican parents raised her with Spanish. As part of the fourth-grade news crew at Casita, Gomez has quickly improved her English fluency.

Their program includes a team of anchors, a sports reporter and behind-the-scenes graphic designers. All of them are fourth graders.

“Everything that we learn they taught us in a fun way,” Gomez says.

Most of the students at Casita are from low-income families. Forty percent speak English as a second language. Yet they’re outperforming children from more privileged backgrounds.

The magnet elementary school is beating all others in the Vista Unified School District, north of San Diego, on the Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium tests, which evaluate Common Core standards for English language arts and literacy, as well as for math. Casita’s scores are also above state and county averages.

Principal Laura Smith says Casita is effective with children from foreign backgrounds because every classroom is bustling with hands-on, high-energy activity.

“A lot of times while they’re experiencing their learning, while they’re in an innovative environment, it really helps them build their language skills,” she says.

Whether it’s writing on desks to learn math, or caring for fish to learn about the circle of life, Smith says students are fully engaged in what they’re doing.

“It’s all inquiry-based,” she says. “So the cognitive load is on the students, where the students are doing a lot of the thinking and the inquiring and the teachers are facilitating that learning.”

Some of the classrooms at Casita are outside. The school has a front garden and a large natural habitat behind the playground, overflowing with California coastal sage scrub, native plants and animals.

“Our motto has been, 'No child left inside,'” Smith says.

On a recent Wednesday, fifth graders searched the habitat for evidence of mammals and other creatures. They found piles of feathers and scat. They collected water samples from a pond to scrutinize for mosquito eggs and invertebrates.

“It’s fun. We find a lot of animals down here,” says 10-year-old Adrian Contreras, who took pictures for the record.

His parents are from Mexico, and Spanish was his first language. At Casita, his English-language skills have surpassed those of his native language.

“So I’m starting to use it more than Spanish,” he says.

He says he thinks the immersive environment helps him get better at every subject. Science and reading are his favorites.

“You just learn at the pace that you need to,” he says.

Their teacher, Gail Cerelli, pulled a slimy, multi-tiered cube out of the pond and held it up as students crowded around.

“What it is, is an invertebrate trap,” she explained. “It just creates surface area for invertebrates to come in and make little homes and lay their eggs and grow. So what we can do is scrape off some of the gook, take it back to class, put it under a microscope and see what we have. OK?”

“OK!” shouted the students.

Cerelli, a magnet specialist, says students who may be shy about raising their hands or asking questions in a regular classroom get really excited and outspoken in the habitat.

“The kids love to be down here,” she says. “It’s not performance-based. I’m just down there talking about stuff I find interesting.”

Back in one of the classrooms, 9-year-old Isabella Gonzalez measured the roots of a plant in a hydroponics class.

“The roots are … eight,” she says.

The third grade students were learning to grow plants without soil, using nutrients from a fish tank. Gonzalez says the class has helped with her pronunciation of tough words like “system.”

“System, yeah, syth-tem,” she says. “I did a project, and express myself, and I accidentally didn’t know a word and my teacher helped me.”

Casita is an International Baccalaureate candidate school, with teachers developing concept-based curriculum instead of topic-based curriculum. They meet weekly to share ideas about multidisciplinary concepts. An example is “structure creates order,” which they are using in everything from history to science lessons.

The school also gets parents involved. El Cafecito, or “the Little Café,” is a weekly meeting of mothers who make copies, organize binders and laminate posters for teachers.

More: Immigrant student life in the US

Catalina Valladares, the 42-year-old mother of a first grade Casita student, cut apple shapes out of green paper. She says she enjoys coming to the school.

“They’re giving English classes to us mothers who don’t speak it,” she says in Spanish.

In a nearby classroom, fifth graders learned how to code.

Luis Sanchez, 10, typed commands into his keyboard, causing thought bubbles to appear beside little monsters on the screen.

“It’s basically just having fun with the characters, making them say something, whatever you want,” he says.

Sanchez "re-classified" in first grade, meaning he passed internal school tests to evaluate his English-language competency. Students take English anguage classes at Casita until they re-classify.

“My parents were born in Mexico, so they really don’t understand English,” he says.

He still speaks Spanish at home, but his English — and coding skills — are outstanding.

Share your thoughts and ideas on Facebook at our Global Nation Exchange, on Twitter @globalnation, or contact us here.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?