Moms go on a hunger strike to get themselves and their kids out of immigration detention

A U.S. Army helicopter lands in Kuwait in 2009. An existing logistics base in Kuwait will expand and transform into a combat force, later this year. (U.S. Army photo.)

Lisseth has been locked up in family immigration detention for close to 365 days with her 6-year-old and she wants it to be known.

That’s why she joined a hunger strike at Berks County Residential Center in Pennylvania. After 16 days of skipping the three meals offered, Lisseth says she began to feel weak and nauseated. She is from El Salvador and crossed the southern border in Texas to seek asylum in the US. She fears retaliation for speaking to the press, so she asked us not to use her real name.

Lisseth was among 22 women who initiated a hunger strike on August 8. Four of them, they say, have been detained with their children for almost a year. Homeland Security Secretary Jeh Johnson said in a statement that his agency was in compliance with a federal judge’s order “ensuring the average length of stay at these facilities is 20 days or less.”

“We come to this country and they say it is a country of laws. But I don’t think it’s that way any more. How can they have a child who is 2 years old, 5 years old, locked up for almost a year?” asks Lisseth, who is 22 years old, in a phone-call in Spanish from the detention center on Tuesday.

That same day, the group announced the strike would come to a halt for seven days, during which time the women will eat one meal daily, giving time to Immigration and Customs Enforcement officials to consider their plea for immediate release.

But Lisseth says there was another concern.

“We’ve been threatened by immigration, doctors and a psychologist here in the center. They are threatening us that if we continue the hunger strike we will be weak and the government would have to take custody of our children,” she says.

An ICE spokesperson says they do not retaliate against anyone conducting a hunger strike and provided this official statement: “The safety, well-being and housing conditions of those in US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) care are of utmost importance to the agency. The agency remains committed to ensuring that all individuals in our care are housed humanely and that they have access to legal counsel, visitation, recreation and quality medical and mental health.”

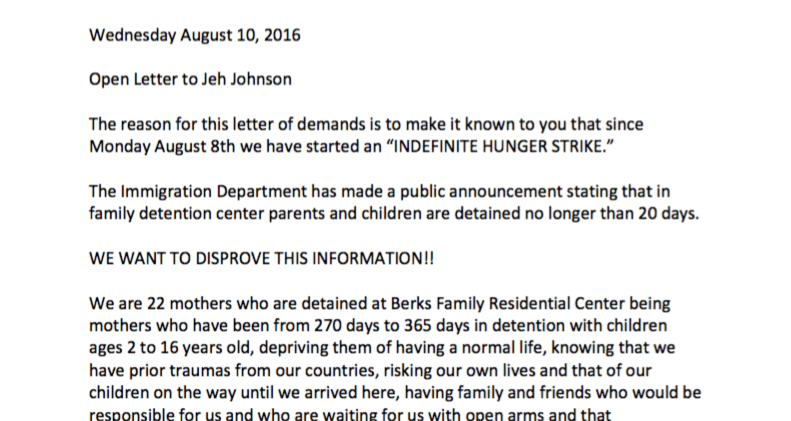

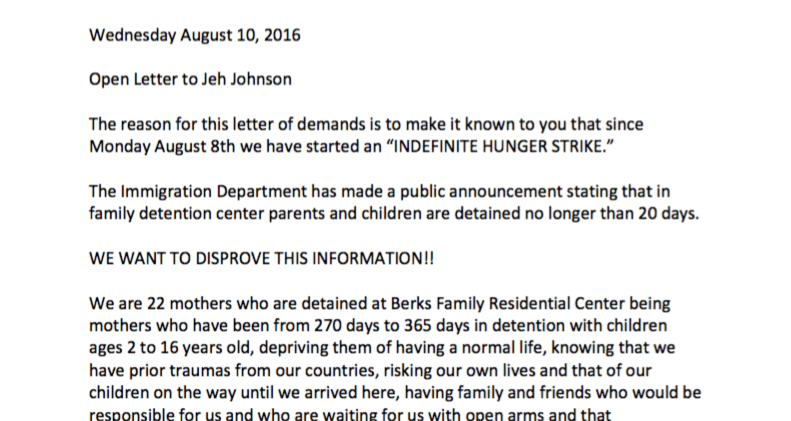

The women sent a letter to Johnson on August 10, two days after initiating the strike, one version in Spanish and one in English: “We are 22 mothers who are detained at Berks Family Residential Center being mothers who have been from 270 days to 365 days in detention with children ages 2 to 16 years old, depriving them of having a normal life, knowing that we have prior traumas from our countries, risking our own lives and that of our children on the way until we arrived here, having family and friends who would be responsible for us and who are waiting for us with open arms and that immigration refuses to let us out.”

“As much as these women have a sense of desperation and really don’t know what their future brings, they’re incredibly resilient,” says Dr. Alan Shapiro, a senior medical director for Community Pediatric Programs at the Children’s Hospital in the Bronx who visited the women last week. “I was impressed by how these women have stuck together and how they support each other, and each others’ children.”

Shapiro says most of the women complained that they are not receiving appropriate mental health care. He conducted mental health screenings on several of the women being held at Berks.

“They score extremely high for depression and for traumatic stress disorder and none of them were receiving care,” he says.

The children held in the facility are also starting to present what Shapiro calls “behavioral regressions,” when children unlearn things they used to know. One child was wetting his bed and another girl gained significant weight because she was overeating, he says.

“Some of the teenagers have thought to break the window and escape. Their frustration is so high that they’re incredible stressed,” says Lisseth.

More about life at Berks: These asylum-seekers are being forced to raise their kids in immigration ‘jails’

Immigration attorneys representing the women argue that the federal government is violating a judge’s order to release them. In Flores v. Holder, a federal judge ruled that children and their parents should be released if the parent does not pose a security or flight risk. In July, a three-judge panel in the 9th Circuit US Court of Appeals ruled that children must be released quickly from family detention centers like Berks, but not necessarily their parents (PDF).

In court documents, the government has said that detention is a way to discourage more people from coming to the country illegally.

“The stated goal of trying to deter people from coming, it’s never been a reality. People are leaving because their lives are in danger there,” said Marc Van Der Hout, a civil rights and immigration attorney in San Francisco who represents some of the women at Berks in civil lawsuits. “These are legitimate refugees.”

Lisseth says some women and children have been released during the hunger strike, but she feels it has been arbitrary. Others are being kept in detention. She thinks it is because they are part of a lawsuit that is challenging how their asylum hearings were conducted in the first place.

“What we are alleging is that the women and children received unfair asylum hearings at the border, where they didn’t have attorneys, where they really didn’t understand the process and where they were still traumatized by the events in their country and the trip to the US,” says Lee Gelernt, deputy director of the American Civil Liberties Union National Immigrants Rights Project, who filed the suit last November.

The government said in the case, Castro v. Department of Homeland Security, that they don’t believe the federal courts have authority to review those cases at the border.

While the case, which poses constitutional questions, is resolved, the women at Berks can’t be deported. But they are not being released from detention either. That’s how someone like Lisseth ends up spending a year in the facility.

The government filed a memorandum in June in the Flores case, saying that most of those who have stayed longer than 20 days in residential facilities didn’t pass a credible fear interview that would open the doors for them to begin the asylum process.

Still, these women have successfully postponed being removed from the country by other means.

“Any immigrant who is specially asking for asylum is going to exercise their rights, whatever their right is, to keep from being deported to what they believe would be certain death. Our government is basically punishing them for doing that,” says Carol Anne Donohoe, an attorney who is representing several of the women detained at Berks. “What more vulnerable population could you target?”

“We’ve been threatened by immigration, doctors and a psychologist here in the center. They are threatening us that if we continue the hunger strike we will be weak and the government would have to take custody of our children. Supposedly, psychologist and doctors are there to help you, not to make you give up faster.”

On Tuesday, the women in the hunger strike, who now call themselves Madres Berks, released another statement: “While we are happy that some of our compañeras have been released, we are outraged that they discriminate against others. The officials say they cannot do anything for those of us who are part of the federal case, they discriminate against us because we had the courage to ask for help from the federal courts to fight for our cases.”

Donohoe represented two of the women who are not part of the ACLU lawsuit. They did not pass their credible fear interviews, but were recently released from Berks.

When asked about the women’s allegations of retaliation based on them being part of the ACLU lawsuit, ICE said they couldn’t comment on pending litigation.

ICE says Berks is not a secure facility — that the women and children held there are not being detained — because families are free to leave. In a statement presented in court this June, Joshua G. Reid, an assistant field office director for ICE in Pennsylvania, said: “There are no physical impediments to a resident departing the facility. If a resident were to leave BFRC [Berks] without authorization, however, they would be considered a fugitive and subsequently may be arrested by ICE officers, depending on the circumstances of their departure and their individual case.”

“We’re told that we have freedom, but when we go outside there’s a fence, and we’ve been told they’ll charge us criminally and it will go on our record,” says Lisseth. “The word freedom goes as far as that fence for us. After that fence we know the consequences.”

Lisseth has been locked up in family immigration detention for close to 365 days with her 6-year-old and she wants it to be known.

That’s why she joined a hunger strike at Berks County Residential Center in Pennylvania. After 16 days of skipping the three meals offered, Lisseth says she began to feel weak and nauseated. She is from El Salvador and crossed the southern border in Texas to seek asylum in the US. She fears retaliation for speaking to the press, so she asked us not to use her real name.

Lisseth was among 22 women who initiated a hunger strike on August 8. Four of them, they say, have been detained with their children for almost a year. Homeland Security Secretary Jeh Johnson said in a statement that his agency was in compliance with a federal judge’s order “ensuring the average length of stay at these facilities is 20 days or less.”

“We come to this country and they say it is a country of laws. But I don’t think it’s that way any more. How can they have a child who is 2 years old, 5 years old, locked up for almost a year?” asks Lisseth, who is 22 years old, in a phone-call in Spanish from the detention center on Tuesday.

That same day, the group announced the strike would come to a halt for seven days, during which time the women will eat one meal daily, giving time to Immigration and Customs Enforcement officials to consider their plea for immediate release.

But Lisseth says there was another concern.

“We’ve been threatened by immigration, doctors and a psychologist here in the center. They are threatening us that if we continue the hunger strike we will be weak and the government would have to take custody of our children,” she says.

An ICE spokesperson says they do not retaliate against anyone conducting a hunger strike and provided this official statement: “The safety, well-being and housing conditions of those in US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) care are of utmost importance to the agency. The agency remains committed to ensuring that all individuals in our care are housed humanely and that they have access to legal counsel, visitation, recreation and quality medical and mental health.”

The women sent a letter to Johnson on August 10, two days after initiating the strike, one version in Spanish and one in English: “We are 22 mothers who are detained at Berks Family Residential Center being mothers who have been from 270 days to 365 days in detention with children ages 2 to 16 years old, depriving them of having a normal life, knowing that we have prior traumas from our countries, risking our own lives and that of our children on the way until we arrived here, having family and friends who would be responsible for us and who are waiting for us with open arms and that immigration refuses to let us out.”

“As much as these women have a sense of desperation and really don’t know what their future brings, they’re incredibly resilient,” says Dr. Alan Shapiro, a senior medical director for Community Pediatric Programs at the Children’s Hospital in the Bronx who visited the women last week. “I was impressed by how these women have stuck together and how they support each other, and each others’ children.”

Shapiro says most of the women complained that they are not receiving appropriate mental health care. He conducted mental health screenings on several of the women being held at Berks.

“They score extremely high for depression and for traumatic stress disorder and none of them were receiving care,” he says.

The children held in the facility are also starting to present what Shapiro calls “behavioral regressions,” when children unlearn things they used to know. One child was wetting his bed and another girl gained significant weight because she was overeating, he says.

“Some of the teenagers have thought to break the window and escape. Their frustration is so high that they’re incredible stressed,” says Lisseth.

More about life at Berks: These asylum-seekers are being forced to raise their kids in immigration ‘jails’

Immigration attorneys representing the women argue that the federal government is violating a judge’s order to release them. In Flores v. Holder, a federal judge ruled that children and their parents should be released if the parent does not pose a security or flight risk. In July, a three-judge panel in the 9th Circuit US Court of Appeals ruled that children must be released quickly from family detention centers like Berks, but not necessarily their parents (PDF).

In court documents, the government has said that detention is a way to discourage more people from coming to the country illegally.

“The stated goal of trying to deter people from coming, it’s never been a reality. People are leaving because their lives are in danger there,” said Marc Van Der Hout, a civil rights and immigration attorney in San Francisco who represents some of the women at Berks in civil lawsuits. “These are legitimate refugees.”

Lisseth says some women and children have been released during the hunger strike, but she feels it has been arbitrary. Others are being kept in detention. She thinks it is because they are part of a lawsuit that is challenging how their asylum hearings were conducted in the first place.

“What we are alleging is that the women and children received unfair asylum hearings at the border, where they didn’t have attorneys, where they really didn’t understand the process and where they were still traumatized by the events in their country and the trip to the US,” says Lee Gelernt, deputy director of the American Civil Liberties Union National Immigrants Rights Project, who filed the suit last November.

The government said in the case, Castro v. Department of Homeland Security, that they don’t believe the federal courts have authority to review those cases at the border.

While the case, which poses constitutional questions, is resolved, the women at Berks can’t be deported. But they are not being released from detention either. That’s how someone like Lisseth ends up spending a year in the facility.

The government filed a memorandum in June in the Flores case, saying that most of those who have stayed longer than 20 days in residential facilities didn’t pass a credible fear interview that would open the doors for them to begin the asylum process.

Still, these women have successfully postponed being removed from the country by other means.

“Any immigrant who is specially asking for asylum is going to exercise their rights, whatever their right is, to keep from being deported to what they believe would be certain death. Our government is basically punishing them for doing that,” says Carol Anne Donohoe, an attorney who is representing several of the women detained at Berks. “What more vulnerable population could you target?”

“We’ve been threatened by immigration, doctors and a psychologist here in the center. They are threatening us that if we continue the hunger strike we will be weak and the government would have to take custody of our children. Supposedly, psychologist and doctors are there to help you, not to make you give up faster.”

On Tuesday, the women in the hunger strike, who now call themselves Madres Berks, released another statement: “While we are happy that some of our compañeras have been released, we are outraged that they discriminate against others. The officials say they cannot do anything for those of us who are part of the federal case, they discriminate against us because we had the courage to ask for help from the federal courts to fight for our cases.”

Donohoe represented two of the women who are not part of the ACLU lawsuit. They did not pass their credible fear interviews, but were recently released from Berks.

When asked about the women’s allegations of retaliation based on them being part of the ACLU lawsuit, ICE said they couldn’t comment on pending litigation.

ICE says Berks is not a secure facility — that the women and children held there are not being detained — because families are free to leave. In a statement presented in court this June, Joshua G. Reid, an assistant field office director for ICE in Pennsylvania, said: “There are no physical impediments to a resident departing the facility. If a resident were to leave BFRC [Berks] without authorization, however, they would be considered a fugitive and subsequently may be arrested by ICE officers, depending on the circumstances of their departure and their individual case.”

“We’re told that we have freedom, but when we go outside there’s a fence, and we’ve been told they’ll charge us criminally and it will go on our record,” says Lisseth. “The word freedom goes as far as that fence for us. After that fence we know the consequences.”

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?