A new generation of Canadians are learning this language, and not all of them are tribal members

Anne Jimmie grew up speaking Ktunaxa, only to lose much of the language when she was removed from her family and placed in a boarding school. In 2006, the Canadian government compensated Jimmie and about 80,000 other First Nations people as part of a class action settlement.

Anne Jimmie is 68 and one of the last native speakers of Ktunaxa, a language unrelated to any other.

Ktunaxa Nation’s traditional lands sprawl from Idaho, Montana and western Washington into British Columbia — which is where Jimmie grew up, not far from the Idaho border.

I went to British Columbia to meet Jimmie and other Ktunaxa speakers, on assignment for The World in Words podcast.

Until she was 5, Ktunaxa was the only language Jimmie spoke. Then one day, her grandfather delivered some unexpected news: She was going to school.

“My grandfather told me that I was going to learn how to read,“ Jimmie told me. “I couldn't wait to go to school.”

She remembers getting in the car with her parents and driving for more than 100 miles, until they finally arrived at a huge gray building where they were greeted by a priest and some nuns.

“I didn’t really pay much attention, didn’t notice that a suitcase was being carried,” says Jimmie. “One of the nuns came toward me and started talking to me. Of course, I didn't understand what she was saying. When I looked, my parents were gone.”

For the next eight years, St. Eugene’s Indian Residential School in Cranbrook, British Columbia, was Jimmie’s home. There were only a couple of other Ktunaxa kids there. They would whisper, “because if you were caught speaking [Ktunaxa], you got punished. You got your mouth washed out with soap. You got spanked with a hard brush or a belt that was pretty wide and pretty thick and hurt a lot. So you can imagine, I learned English pretty quick.”

Today, St. Eugene's is a casino resort with a golf course owned by Ktunaxa Nation.

Ktunaxa — among many other languages — was pushed to the brink of extinction by Canada’s boarding schools for indigenous children. When Jimmie returned home from St. Eugene’s, she refused to speak her mother tongue.

“I remember telling my grandfather, the very person that told me and excited me about going to school, ‘Speak English, I don't know what you're saying,’” she says. “I was so brainwashed. And I know he was hurt by that.”

Years went by. Jimmie grew up, had children — and never spoke Ktunaxa with them.

“I still was suffering from all the strappings I got. If I want to say what happened, it was that my language was beaten out of me.”

It’s a painful chapter of Canadian history the government has grown to regret. In 2008, Canada’s prime minister, Stephen Harper, issued an official apology to the First Nation people. The government established a Truth and Reconciliation Commission, and paid reparations to people like Jimmie, who suffered years of abuse at the boarding schools.

On the micro-level, things changed for Jimmie, too: She had a granddaughter. Jenni Jacobs didn’t grow up speaking Ktunaxa, but heard it enough to realize she was missing something.

“I taught myself a little bit of Spanish and all these other languages,” Jacobs says. “Then I asked the question, ‘Why didn't you learn your own language?’ And that's when I started looking at the words and teaching myself.”

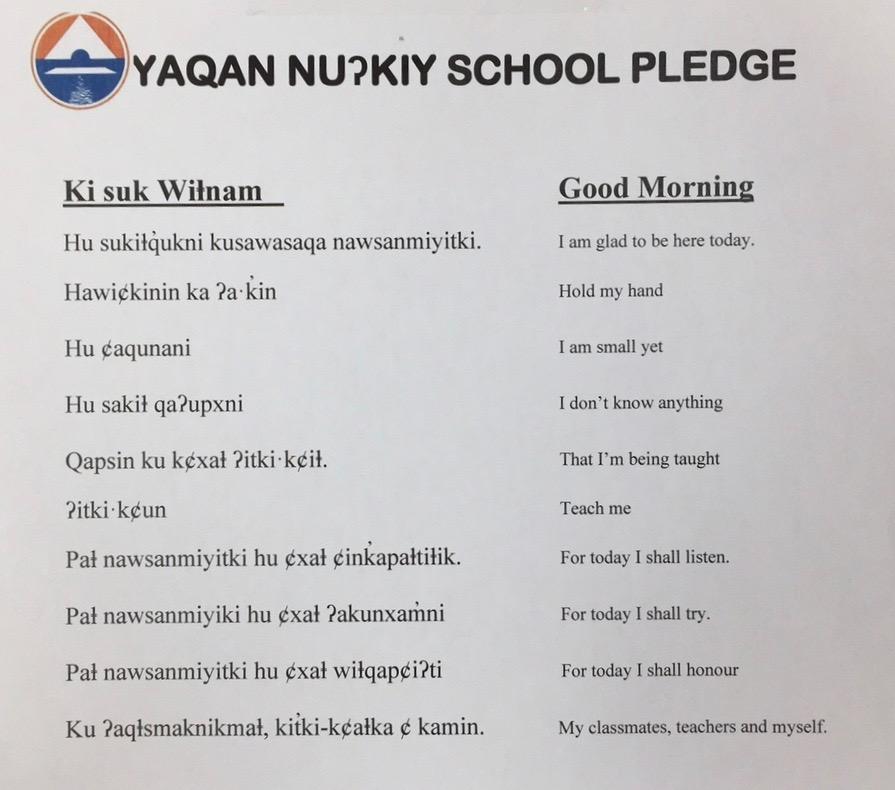

Today, Jacobs is the language and culture teacher at Yaqan Nu?kiy, the Ktunaxa reservation school in Creston, British Columbia. From the look of written Ktunaxa, it’s not an easy job. The language is peppered with glottal stops, question marks, apostrophes, cent signs and a mysterious double barred “l.” Jacobs had to get creative to help students wrap their tongues around unfamiliar sounds:

Just a few years ago, it looked like Jacobs might not have any students left to teach.

The Ktunaxa have been dispersed by the same economic forces affecting rural native tribes everywhere — and I mean rural: my GPS couldn’t even find the reservation. There are only about 200 members left on the reservation.

“With the housing situation, and the employment situation, a lot of families have moved off the reserve,” says Yaqan Nu?kiy principal Karen Smith. “When I started here three years ago, there were 19 kids.”

Then something unexpected happened: In those three years, enrollment nearly quadrupled. There are now 74 kids at the school.

“We have somehow caught on in the community and [become] a school of choice,” says Smith. Another unexpected thing: Only 12 of these students are Ktunaxa. But all of them are studying the indigenous language and culture — which ironically, may just end up being what saves it.

Yaqan Nu?kiy may be rich in enthusiasm, but the budget for its language program is zero. School principal Karen Smith says, in contrast to the generous funding that, for example, French immersion programs receive, there is no money available for Ktunaxa instruction. “Even after the apology and the Truth and Reconciliation report, they just won't even put it on the table for discussion.”

The new Trudeau government has promised to increase funding for indigenous language revival. But for now, the school relies on elders, like Anne Jimmie, to preserve a language they were once forced to forget.

Podcast Contents

03:40 Ryan McMahon, host of Red Man Laughing podcast introduces himself.

05:30 Nina and Patrick display their ignorance of Canadian geography.

06:50 Alina Simone tells Anne Jimmy's story.

10:30 What is the value of an apology?

20:01 Jenni Jacobs teaches herself Ktunaxa.

20:50 What Ktunaxa sounds like.

25:40 Ryan McMahon's epic rant on truth and reconciliation.

30:05 Guess the accent!

You can follow The World in Words stories on Facebook or subscribe to the podcast on iTunes.