Today’s movement toward sustainable living echoes the not-so-distant past

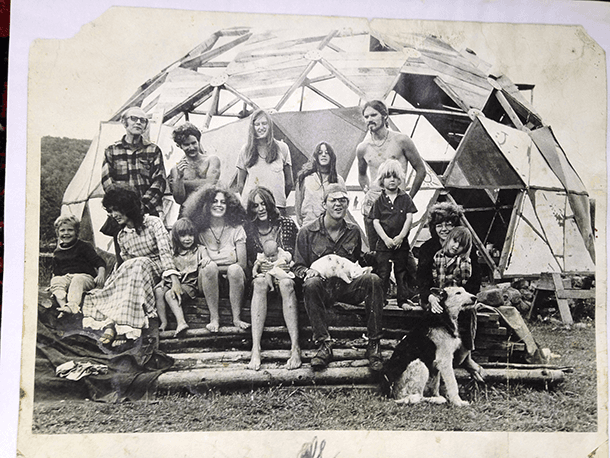

Members and friends of the Myrtle Hill commune, in northern Vermont, gather in front of a geodesic dome in the summer of 1971.

As interest in sustainable, organic food has grown, so have the numbers of young entrepreneurs taking up farming to grow crops to sell directly to restaurants and at farmers markets. But, the movement is hardly new.

In the 1960s and 70s, many idealistic young Americans left cities and suburbs to build their own version of the American dream together on communal farms, often without a clue how to farm sustainably.

Author Kate Daloz’s new book, "We Are As Gods: Back-to-the-land in the 1970s and the Quest for a New America," brings us stories of this movement from the homesteaders and communards of the time. And she writes with authority: Daloz grew up in a geodesic dome house assembled by her parents in northern Vermont, not far from several of the most well-known communes.

Daloz’s parents had been in the Peace Corps prior to joining the back-to-the-land movement. One day her dad had a profound revelation, Daloz says: “He was in a village and realized he was the only person in the village at the time who didn't know how to build a house and didn't know how to make his own clothes — and he had a doctorate at that point. He suddenly was horrified to realize that for actually living day-to-day and surviving, he was useless.”

Her mother wanted the opportunity to do things she had been told as a girl she wasn't capable of doing, and she wanted the freedom to test her own strength, Daloz says.

In addition, many young people rebelled against what they saw as the conformity of a 1950s childhood, Daloz says. They didn't want the same “two-parents-in-the-suburbs-living-by-themselves life,” so they banded together in groups and, in a lot of cases, moved to the country.

“They wanted to build their own houses, they wanted to grow their own food, and they wanted to learn skills they didn't feel they had access to,” Daloz says. “They went together because in the early days, especially, they needed a whole group of people to make that experiment.”

“What I really admire about the mindset of the people who did this is they just thought they could do it,” Daloz continues. “They let themselves invent and they let themselves discover and they let themselves struggle. … I really appreciate the attitude of putting yourself in a situation and figuring it out and inventing something new along the way.”

In retrospect, Daloz says, the movement’s successes and failures seem completely predictable, even to anyone who has ever just had roommates. “You know, ‘Who's going to do the dishes? What's the standard of cleanliness that we're going to keep?’ And we’re often talking about places that were committed to no electricity and no running water.”

People who started out thinking, ‘We'll form a non-suburban kind of community and live in one big house together’ discovered that privacy is not such a bad idea, after all, Daloz says. Parenting with two people is hard enough, but try doing it with 20 other people who are not related to your children. “I heard from a lot of communards that they hit a turning point in their commitment to a commune when they saw other members of the community reprimand their child in a way that was not how they would do it.”

People in the commune also inadvertently fell into rigid gender roles, Daloz says. “They didn’t mean to. They were thinking of themselves as very radical. But … the women [often] ended up doing a lot of the cooking and cleaning.”

Many members of the movement, her parents included, were also quite naïve about the difficulties of living a “simple life,” Daloz says. “It involved less commercial goods, but hauling water by hand, cutting your own firewood — none of that is simple. It's incredibly difficult,” Daloz says. ‘[Many] people, my parents included, talked about how many hours it took in a day to just make dinner or just heat your house. So they were surprised by that, but they learned a lot from it too.”

On the other hand, the ’70s generation helped develop organic practices, co-ops and natural food systems that now give the general public access to things they didn't have in 1962. Today, we expect to see items like crunchy peanut butter and yogurt in our supermarkets, but those things came about as a result of these experiments in the 1970s, Daloz says.

To Daloz, today’s homesteaders and farmers seem less naïve, especially about the realities of a cash economy. Daloz gets the impression that the experimenters of this era are thinking more seriously about how they will make a living once they get ‘back to the land,’ in a way the 1970s generation didn’t. Back then, she says, people just left and figured it out when they got there.

“It was very surprising to me the number of back-to-the-landers who really thought they could just walk away from a cash economy and were kind of shocked to realize that it's not that fun to be cold and impoverished and living under these austere conditions.”

In those post-war economic boom times, they were also more confident about getting a good job if the experiment failed, Daloz says. Today’s generation is facing a much more difficult economy.

This article is based on an interview that aired on PRI's Living on Earth with Steve Curwood.