Donald Trump fuels citizenship drive among immigrants

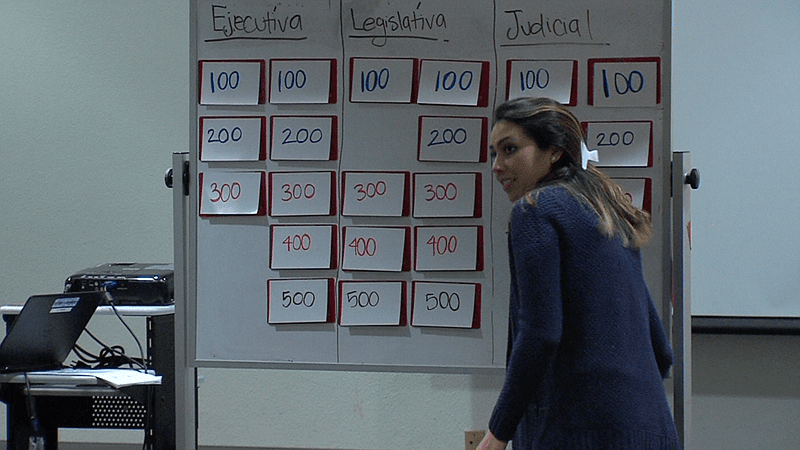

A California State University San Marcos volunteer leads a Cultivando Liderazgo workshop that helps immigrants prepare for the US citizenship test.

It has been nearly half a century since Concepción Álvarez, a 75-year-old Mexican immigrant who lives in Vista, California, became eligible for US citizenship. But it wasn’t until this year that she decided to dive into the naturalization process. The reason? She points to Republican presidential frontrunner Donald Trump.

“I think we are all waking up, because we’ve never heard things so ugly as what that man says,” Álvarez says.

Álvarez is among a rising number of Latino immigrants rushing to become citizens so they can vote in the 2016 presidential elections. Many say they are spurred by fear of Trump, who has proposed deporting millions of immigrants and building a 2,000-mile wall between the United States and Mexico.

“It seems he doesn’t like us,” Álvarez says. “But we don’t like him either. We don’t want him to be president.”

Not all Latino immigrants feel the same way, as evidenced by Facebook groups with names like "Latinos/Hispanics for Trump." But out of dozens informally surveyed across the San Diego area, those seeking naturalization this year say they were doing so to vote against Trump, not for him.

Nationwide, citizenship applications totaled more than 202,000 during the fourth quarter of last year, up 14 percent from the same quarter in 2014, according to US Citizenship and Immigration Services.

In San Diego County, the effect is most pronounced in certain neighborhoods. In Chula Vista, where more than half of the population is Latino, citizenship applications jumped 40 percent in the fourth quarter of 2015, compared to the same period the previous year. About 8.8 million US residents are eligible for citizenship.

oembed://https%3A//www.youtube.com/watch%3Fv%3DTyg4bI60BvU

The increased citizenship interest among Latinos has contributed to a spike in programs meant to lend them a hand in the process, such as a series of workshops called Cultivando Liderazgo, led by the National Latino Research Center at California State University San Marcos. “So what it means is essentially nurturing or cultivating leadership,” says director Arcela Nuñez-Álvarez.

The workshops are free and held in public spaces across the county, including libraries, schools and churches. The curriculum includes the content of the citizenship test and a review of US politics and history, with activities designed to help immigrants memorize the material, such as games of Jeopardy. Additionally, the workshop leaders, Cal State University San Marcos volunteers, connect prospective citizens with lawyers and other resources to help them naturalize.

Civic engagement among Latinos in the county is low considering the size of the population, Nuñez-Álvarez says, but the tide is shifting. “Trump is definitely a big factor that I think is really pushing people to think about what kind of government we want to have, if he really represents immigrants, Latinos,” she says.

Preparing the Latino community with workshops

On a recent Wednesday evening, Nuñez-Álvarez led a Cultivando Liderazgo workshop at a library. She passed out Crayola boxes to more than 20 immigrants, including Álvarez, who filled in a map of the United States to help herself memorize the names of the US-Mexico and US-Canada border states. One of the questions on the citizenship test asks applicants to name border states.

Álvarez has been attending these weekly workshops for three months with the hope of becoming a citizen in time for the coming presidential elections. “I want Clinton’s wife to win,” Álvarez says. “She looks at us (Hispanics) with more affection, and her husband was a good president. I like her.”

Álvarez says what she most dislikes about Trump are his proposals to revoke the citizenship of children born to immigrants who are in the country illegally. She recalls facing discrimination at a restaurant where a waiter didn’t want to serve her when she first arrived in the United States more than 50 years ago.

“Back then, it didn’t hurt so much. I said, ‘Whatever, it’s their country,’ but lately, no, we’ve done so much for this country,” she says, citing her management of a Mexican restaurant and her seven US-citizen children. Some of her children are teachers and social workers.

“I think we belong now," Álvarez says. "It’s not fair for others to perceive us another way.”

She considers herself an American, too. Now, she just intends to make it official.

Recruiting the youth to help

Álvarez is going to take the US citizenship test in Spanish because she is over 50 and has been in the country for more than 20 years, which exempts her from the English-language requirement. But some immigrants must take the test in English to demonstrate fluency, such as Eufrocina Frías de Martinez, a 66-year-old Escondido resident who came to the US 16 years ago from the Mexican state of San Luis Potosí.

She has been eligible for citizenship for more than a decade, but says she's going through the process now because she wants to vote against Trump if he becomes the Republican nominee. One problem: Martinez doesn’t speak English. But Cultivando Liderazgo has improvised a solution by recruiting young immigrants to help their parents and other community members prepare.

Nuñez-Álvarez of Cultivando Liderazgo says young immigrants are often bilingual, unlike their parents. So students who learn the material can share the knowledge. Moreover, family is central in Latino culture, and immigrants are more likely to naturalize when encouraged by a relative.

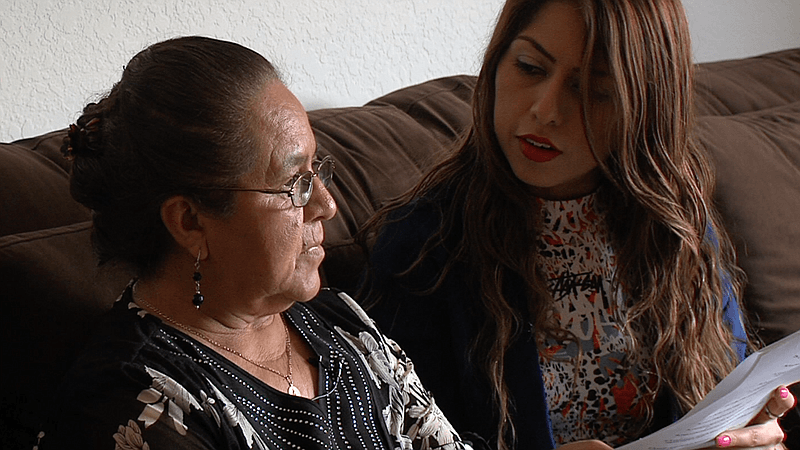

Martinez’s 26-year-old daughter, Lucero, is a student at California State University San Marcos and attends the Cultivando Liderazgo workshops, which take over her regular Spanish class once a week. After one of the workshops, she returns home and sits on the living room couch with her mother, reading from a list of more than 100 questions. She reads the questions in English and then in Spanish, asking her mother to repeat the answers in both languages.

“In what month do we vote for a new president?” Lucero askes her mother in Spanish.

“Noviembre,” they say together.

“Es, ‘November,’” Lucero says, translating.

“November,” Eufrocina tried in her accent.

Lucero says she hopes to vote for Hillary Clinton. "We have never had a woman [president], and I'm interested in what her perspective could be," she says.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!