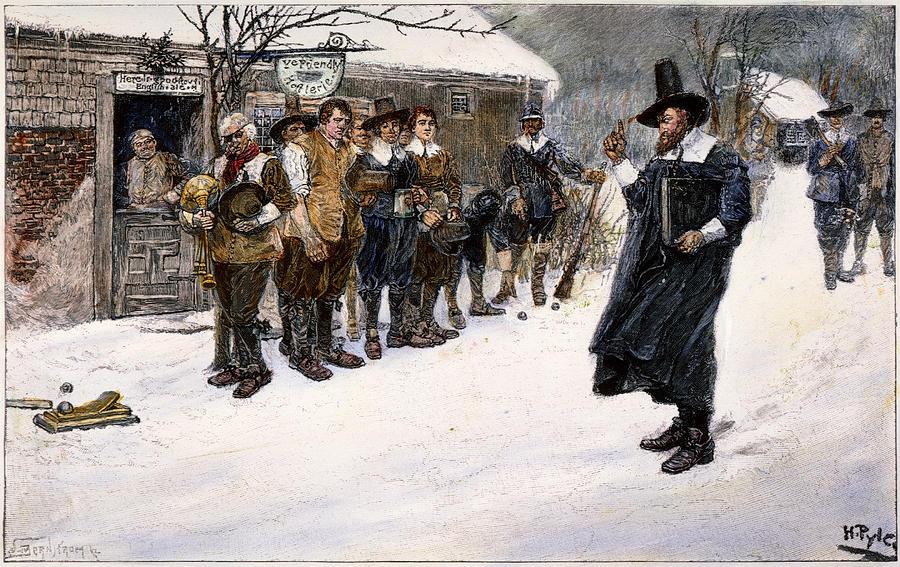

“The Puritan Governor interrupting the Christmas Sports,” c. 1883.

It's pretty common to hear people complaining about the so-called "War on Christmas." Whoever designs the cups at Starbucks knows what we’re talking about.

But the US relationship with the Christian holiday is pretty complex.

Did you know, for example, that Christmas used to be illegal in Massachusetts and much of New England? And it remained taboo in that part of the country until at least 1870, when the Feds declared it a national holiday.

Massachusetts was founded in the 1620s by English folks seeking to practice their form of Christianity in their own way, and that definitely did not include Christmas.

They were called Puritans because they wanted to purify the church and the Christian faith of its pagan legacies: all those ancient customs rooted in Germanic and Celtic folklore. They were just anathema. Things like touching a piece of holly to a yule log for luck; or decking your halls with boughs of holly and ivy; or making fires and lighting candles; or hanging gaudy decorations; or carousing and singing to keep the sun alive; or going ‘a-wassailing’ (going house-to-house singing carols); or putting on mummers plays.

The Puritans thought these things were all extremely un-Christian, and they fought hard to stamp out this nonsense in their new "cittie upon a hill," their new godly colony, their new Jerusalem. Even feasting was not approved. Instead of yule-tide, they condemned it as fools-tide.

But they're still Christian, right, so one would assume that at least they went to church to celebrate Christ's birth? Nothing could be further from the truth. Unless it fell on the Sabbath, December 25th was treated like an entirely normal day. Everyone was expected to work, or go to school, just like any other day.

The opposition to Christmas was both theological and moral.

Their theological argument was that they saw nothing in scripture to warrant the celebration of Christ's birth. They saw Christmas as a sly trick played by the early Catholic church to graft Christianity onto the older pagan ways of Europe — the customs that had always celebrated the birth of the New Year around the time of the solstice.

Also, Christ was seen as a manifestation of God, and therefore should be revered, but not venerated like an idol.

The Twelve Days of Christmas were also denounced as the most immoral time of the year, full of rude revelry, idleness, hard drinking and promiscuity. Kissing under the mistletoe was right out.

So Christmas was seen by the Puritans as superstitious or even heretical. Ministers could be arrested for holding Christmas services. From 1659 to 1681, anyone caught celebrating Christmas in Massachusetts was subject to a fine of 5 shillings — that was about a week's wages for a laborer.

After 1681, Christmas was no longer a crime, but it remained completely taboo. Anyone caught making merry or singing carols was prosecuted for disturbing the peace, well into the 18th century.

Even gift-giving, or charitable giving, was frowned on as just another ancient mid-winter custom that the Puritans attempted to stamp out in their war on Christmas.

In the rest of the English-speaking world, things were not so bad. The Puritans did take over all of England after a series of civil wars in the 1640s and 50s, and imposed their form of fundamentalist Christianity on the whole of the British Isles. Christmas was outlawed in England in 1647, along with Easter and all other holy days. But needless to say, that was hugely unpopular, and the old ways came back with the restoration of the monarchy in 1660.

That led to lots more Puritans emigrating from England in disgust — which in turn drove the war on Christmas in New England to its highest levels.

Puritans took these customs wherever they settled, from Nassau in the Bahamas to parts of Virginia and New Jersey. But they were not the majority in those places and Christmas survived.

Some social historians suspect that poorer folk and servants who came to New England for work — rather than for faith — may have kept some old customs and traditions alive underground. But what really made the difference in the end was the transformation of the population in this part of the country in the mid-19th century from mass immigration, especially from Ireland.

America’s first War on Christmas eased slowly over the centuries. Prosecutions faded, but it remained culturally taboo. It remained a regular working day, and school day, in Massachusetts until 1870, when the federal government proclaimed it a national holiday. President Ulysses S. Grant thought having a national holiday on Christmas was a way to unify the country after the civil war.

That was 250 years after the first Pilgrims landed on Plymouth Rock.

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?