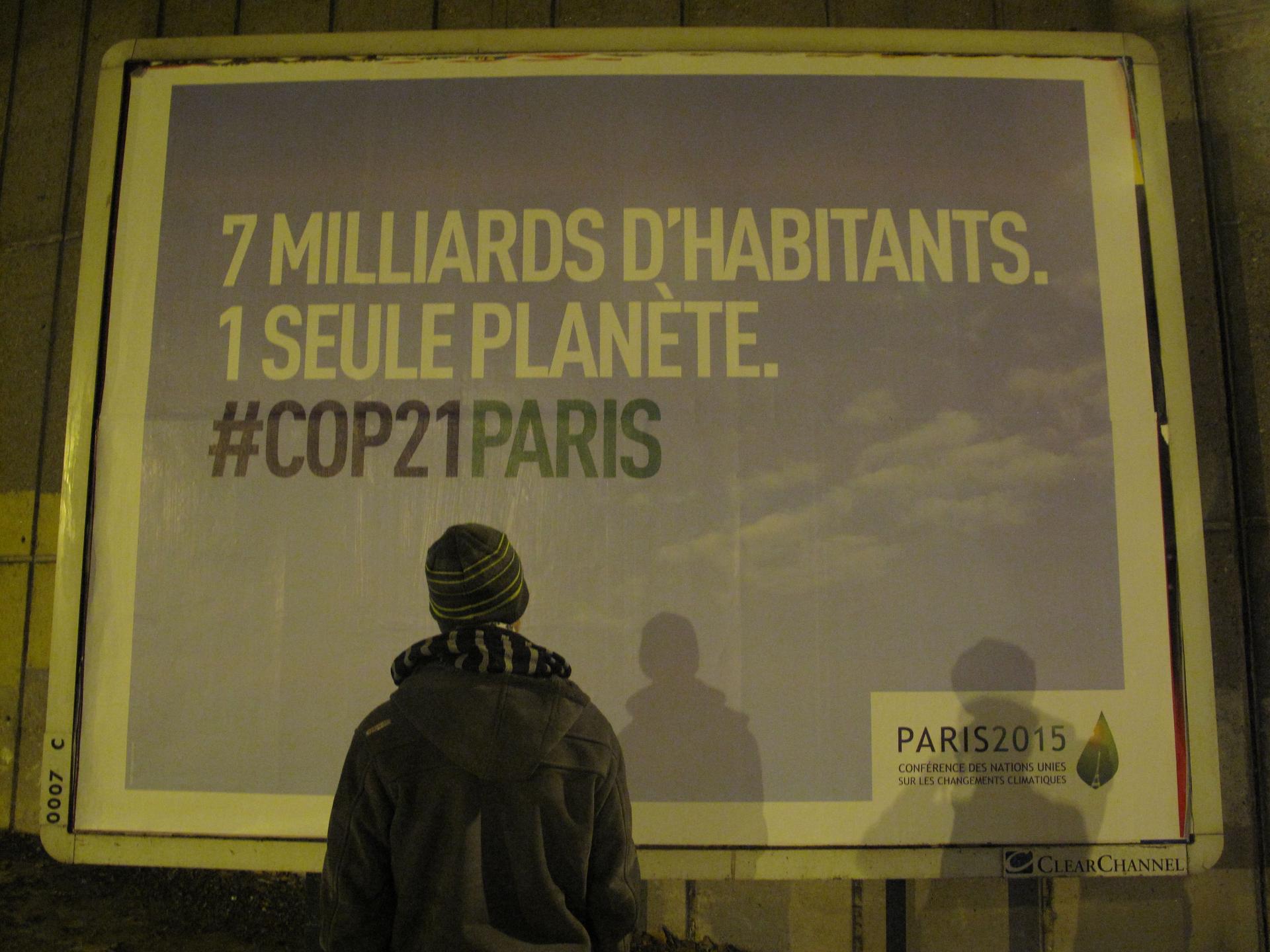

France bans marches, but climate activists make their voices heard

Climate activists formed a 2-mile human chain Sunday along Parisian sidewalks after authorities banned a full-fledged climate march following the Nov. 13 attacks in the French capital. Demonstrators said they were determined to find ways to express their concerns ahead of the UN global climate summit, which began today. The slogan reads " For a Climate of Peace".

A city still on edge. A parade of world leaders streaming in. Forty thousand extra visitors. Demonstrators determined to make their voices heard despite a state of emergency and a ban on marches and rallies.

Such was the scene in Paris as a make-or-break global climate summit got underway today less than three weeks after the attacks of November 13.

The bombings and shootings cast a pall over a city and country that had been determined to help forge a turning point in global efforts to address the climate crisis. But from street activists to the country’s president, the French are professing to be unshaken in their resolve to help break global gridlock on climate.

“There were definitely concerns when the Paris attacks happened that it would overshadow the conference,” said Manon Verchot, a French-American journalist covering the summit for the Ground Truth Project. But Verchot says Holland made it clear in opening the conference this morning that that would not happen.

Follow all of our coverage of the Paris talks and the global climate crisis

"The challenge of an international meeting has never been so great because it's the future of the planet, the future of life," Hollande declared. "There are two big global challenges that we must face" as he urged leaders to create a world free from environmental and extremist destruction.

More broadly, Verchot said, "people are trying to get back to their daily lives." Which among other things includes finding ways to make a show of force on the climate issue while staying within the bounds of the state of emergency.

When authorities announced that a major climate protest scheduled for the day before the summit would not be allowed to proceed, activists said they wouldn't be silenced, and over the weekend they made themselves heard.

On Sunday thousands of people formed a two-mile-long human chain through central Paris to demonstrate their support for action against climate change. The action was the result of what activist Audrey Arjoune said was an ongoing conversation with police.

“We understand what we are not allowed to (do)," Arjoune said, "but what are we allowed actually to do?”

Arjoune said police gave their tacit approval for the human chain as long as people stayed on the sidewalk.

“And then we said, 'OK, let’s play with that, let’s do like a human chain,'” she said. “So let’s put our placards on, and our visuals on, and in the end we have a perfectly legal way of expressing ourselves.”

But not all demonstrators respected the deal. As many people were heading home, a smaller group converged on Republic Square chanting slogans, accusing France of becoming a police state, and hurling rocks, bottles and other objects at riot police. Police responded with tear gas and baton charges before making more than 300 arrests.

A day earlier, Foreign Minister Laurent Fabius had defended the policy of banning protests but not other mass gatherings like soccer games and Christmas markets.

“If they are in fact in a closed environment of course we can guarantee a certain amount of safety and security. But if you’ve got thousands of people walking or marching of course there are risks that we might not be able to manage quite in the same way,” Fabius said Saturday. “This is why the French government has decided to ban marches and most of the associations and organizations have been very responsible in their reactions to this decision.”

But the French government’s actions go further than just banning demonstrations.

The country remains under a three-month state of emergency, invoking a law dating back to the 1950s and the bloody Algerian War. And the government has hinted it wants to go further by amending the constitution to make its powers permanent.

“There have been a lot of proposals, each one more frightening than the other one, I would say,” said Clemence Bectarte, an attorney with the Paris-based International Federation for Human Rights. “And of course this constitutional amendment would allow the government to pass more easily laws on the state of emergency if any attacks happen again.”

Already the state’s emergency powers allow police to restrict people’s liberty on mere suspicion of bad intent.

That’s exactly what happened last week to Joel Domenjoud, a green activist who has been placed under house arrest for the duration of the climate conference with way to challenge it in court.

Despite having no criminal convictions, police ordered him to register three times a day at a nearby police station and not leave his neighborhood. The alternative is six months prison.

Domenjoud is known to police because he represented a group of activists challenging the ban on marches. He says police told him it’s simply too dangerous to allow public gatherings.

“So what I was (asking), was how long will it be? Three months? Three years?” Domenjoud said. “I don’t need some other people to secure my life, I can assume the responsibility myself even if there are some risks.”

Rights lawyers like Bectarte warn that France may be moving too quickly to restrict freedoms. She recounts how critical French society was of the United States in the wake of 9/11, when the Bush administration shepherded in the controversial Patriot Act that expanded warrantless searches and police powers.

“France had so much denounced the adoption of these laws in the US and now France doing the same thing 14 years afterwards, which seems inconceivable,” Bectarte said.

That said, the French government has been buoyed by public support for its tough stance in the wake of the deadly attacks. Despite her personal reservations, Bectarte admits it’s been an effective political strategy.

“People are really petrified and we see this in the polls, the tremendous support of the population in favor of all the measures that have taken so far including the ban on any protest or rallies,” she said.

The need for extraordinary security is especially high this week with nearly 150 world leaders attending the climate conference. So for now, Paris treads an uncomfortable line balancing the demands of two global crises — preventing another attack, while respecting free speech on the climate crisis.

Traci Tong of PRI's The World contributed to this report.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?