Want better thinking and productivity? Improve the air quality in your office.

Twenty-four professionals participated in the six-day COGfx Study. Each conducted their normal work activities within a laboratory-setting that simulated conditions found in conventional and green buildings, as well as green buildings with enhanced ventilation.

Ground-breaking research by a team from Harvard, Syracuse University and SUNY Upstate has found that improving indoor air quality can dramatically improve workers’ cognitive functioning.

When most of us think of ‘air quality,’ we likely consider only outdoor air, with its soup of smog, smoke, dust and other types of air pollution. But most of us spend ninety percent of our time inside. And poor indoor air quality can decrease our ability to think, reason and problem-solve, the new study shows.

Chemicals found in paints, furniture and flooring — so-called volatile organic compounds, or VOCs — are the main problems. But common office concentrations of carbon dioxide also reduce cognitive functioning.

“We found some quite striking results,” says Joe Allen of Harvard’s Center for Global Health and the Environment. “We found a doubling of cognitive performance scores for people who spent time in an optimized green building environment compared to when those same people worked in an indoor environment designed to simulate the conventional office building.”

Three cognitive functioning domains in particular showed the strongest changes, Allen says: crisis response, strategy, and information usage. These cognitive function domains are most closely tied to worker productivity, according to Allen. He says the results, published in Environmental Health Perspectives, were quite surprising.

“To be quite honest, we were shocked,” Allen says. “We think this is a big deal, the findings are strong and the magnitude of the effect is quite large.”

But the most interesting thing about the study, Allen says, is that the researchers weren't testing “anything exotic…We didn't introduce chemicals into the environment that you don't typically encounter; we didn't introduce ventilation rates that are impossible to obtain. The idea was to simulate office environments that can easily be obtained. What's shocking is that you see this big effect and the effort it takes to reach it wasn't that much.”

The scientists ran the study in a simulated office environment at the Syracuse Center of Excellence. They enrolled what they called ‘knowledge workers,’ people who work in office environments, to come to the Syracuse Center of Excellence and do their normal work routine in the office.

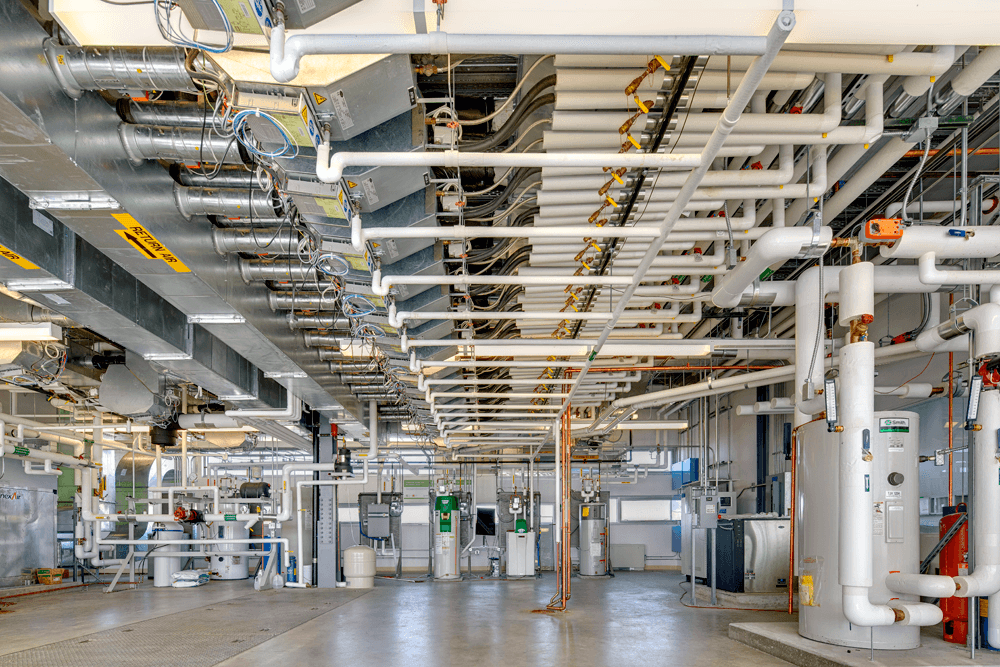

Unbeknownst to the workers, the researchers manipulated the indoor environmental conditions in their workspace from a floor below. At the end of each day, they administered a cognitive performance test. The analysts who administered and scored the tests were also blinded to the test conditions of that day, so it was a double-blind study. In that controlled environment, they were able to manipulate one air quality variable at a time to “tease out the effect of that variable on the cognitive performance scores of people in that space,” Allen says.

Most of us are exposed to VOCs every day in just about every environment we work in and researchers already know they cause things like eye irritation and upper respiratory irritation; some of them are known carcinogens. Now we're learning that they can also impact cognitive function, Allen says.

The results from carbon dioxide levels were a bit more surprising.

In the second part of the study, Allen and his colleagues looked at the impact of carbon dioxide on cognitive function, independent of ventilation. Outdoor carbon dioxide concentrations are typically around 400 parts per million, but people routinely experience indoor carbon dioxide levels between 800 and 1,200 parts per million — and it’s not uncommon to see carbon dioxide as high as 1,500 parts per million or even up to 3,000 parts per million, Allen says.

“We found that when people were moved from an environment with low-carbon dioxide concentrations to a level of about 950 parts per million — a level we find in most indoor spaces — we saw a fifteen percent decrease in cognitive performance scores for the people in that space,” Allen says. “And when they moved to an environment with 1400 parts per million, we saw fifty percent lower cognitive performance scores when they were in that environment.”

That is very big impact, Allen says. “This is new for our field. We measure carbon dioxide all the time when we're doing studies of buildings and health, because it's a good indicator of how well the space is ventilated,” he explains. “But now we’re starting to see that maybe carbon dioxide isn't just a useful proxy for ventilation and for other things that [might be] building up in our environment — it might actually be a direct pollutant, a primary pollutant.”

These findings could directly affect how architects and companies design their buildings and control the indoor environment. “The positive story here is that there are things we can do right now in most spaces that will reduce the chemical concentration that we're exposed to and can increase the amount of air coming in,” Allen says. “We think this will lead to better cognitive performance based on the results of the study.”

John Mandyck, chief sustainability officer for the United Technologies Corporation (UTC), says the findings may revolutionize the way we think about buildings. UTC is the world’s largest provider of building technologies and the key underwriter of the study, though it was not involved in the data collection, analysis, interpretation, or drafting of the peer-reviewed paper.

“If you look at the true cost of operating a building, just one percent is energy,” Mandyck says. “Ninety percent of the true operating cost of a building is the salaries and the benefits of the people inside the building. [If] green buildings can improve thinking, can improve productivity, can improve health, [then] buildings become human resource tools. Buildings can become ways that we can find competitive advantages simply by optimizing the indoor environmental quality.”

This story is based on an interview that aired on PRI's Living on Earth with Steve Curwood