In Italy’s markets, this popular yogurt made by migrants tastes great, and has a side of resilience and hope

As Europe grapples with the Syrian refugee crisis, Italy continues to rescue thousands of other migrants trying to reach the continent via the Mediterranean sea. But those fleeing hunger, not wars, like most Africans, are denied documentation and left in limbo.

In Rome, across the street from an auto repair shop, crates of zucchini, potatoes, lettuce and tomatoes are on display at a kind of pop-up market. At the market, a group of West Africans are showing locals what they can do with a legal permit and fresh milk.

Italian shoppers are asking Saydou, a vender from Gambia, for more of his yogurt. The 26-year-old says he gets giddy when shoppers fight for the remaining jars.

“For these people, it’s very good, my yogurt is very good. They know the yogurt is better, they know its natural,” he says.

It’s not just natural, or organic, or farm-to-table. This yogurt is a symbol of hope — made, jarred and delivered by a group of West African immigrants. Their business idea came from far away — via a dangerous route.

“[The yogurt traveled] from Gambia to Senegal, from Senegal to Mali, from Mali to Niger, from Niger to Libya and from Libya to Italy,” he says.

Seydou traveled 3,000 miles across the desert and sea to get to Italy, a country that pretty much allows African immigrants to do one job — brutal agricultural labor. But seven years later, he’s part of a successful cooperative: African yogurt delivered to homes, markets and restaurants on bicycles.

The founder of the operation is Suleman Diara. He’s the one who saw the opportunity, and put a skinny African cow on a yogurt label.

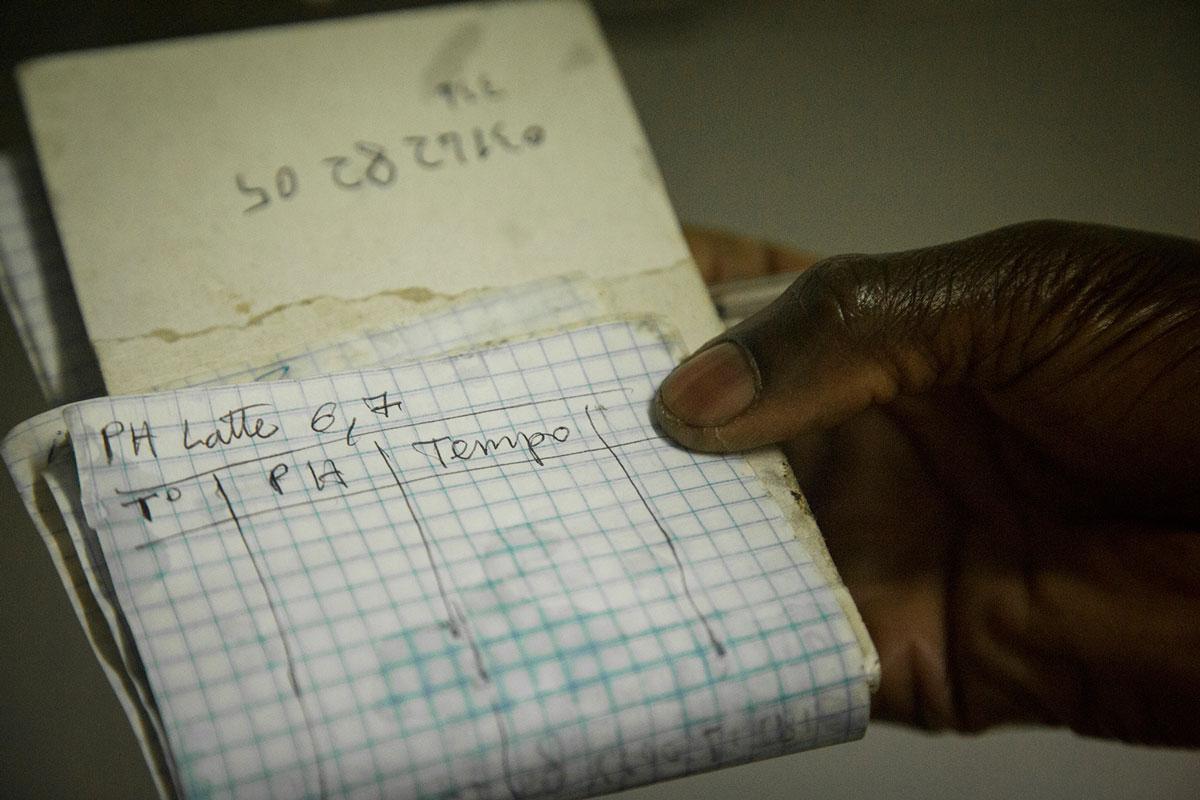

“The project was called Barikama, which means ‘resilient,’” he says. "Resilient because it began with two people, and two liters of milk a week. When we reached 200 liters a week, we decided to call ourselves Barikama, because we had potential to grow. We got this far, facing all these problems, and we believe we can resist, grow and help other people.”

Diara says his first years in Italy were harsh. Like thousands of others who came undocumented, he fell prey to agricultural exploitation in Italy’s south, picking mandarins for $0.05 a case.

He ended up in Rosarno, a town with a bad reputation for violence against immigrants. Saydou was also there, and other Africans who became the Barikama team.

Now they gather in a tiny dairy lab near a lake, in the very pretty Roman countryside. When I went to see them, two of Suleman’s partners are on shift. Cheikh, who is from Senegal, is dressed in full cheese factory garb along with rings and bracelets. There is also someone working named Ismael, from Benin. He’s a soft-spoken accountant with wide glasses that keep steaming up from the heat.

Cheikh pours organic milk into a steel tank and Ismael stirs it with a big wooden spoon. They say this yogurt has changed their lives.

“We are really happy to carry on with this project because we are independent now,” Ismael says. “We don’t have to beg anyone, and we are free to organize our own work without exploitation. We understand each other and we do everything together.”

Ismael says he had a good job in Italy. But he got laid-off and lost his permit to stay. He went under the radar and kept working so he could support his family back in Benin. He became a day laborer in Rosarno.

Cheikh found his way to the yogurt business via the soccer pitch. He had a visa to audition with a professional soccer team, but didn’t make the cut. Then, rather than going home empty-handed, he stayed and picked tomatoes in Rosarno — a time he remembers bitterly.

“Those who know Rosarno know it’s a racist place,” he says. “If an African buys an espresso at a cafe, they give it to you in a plastic cup. [But], they serve it to white people in a proper espresso cup. You can’t walk around at night, because people throw rocks at you, and drivers slam the doors of their cars open to hit you. Total racism."

In Rosarno, migrants live in shacks without running water. They work 12 hours a day for no more than $25. And a big chunk of it goes to local recruiters.

African day laborers, who flee their countries to escape poverty, swarm the Italian coast and countryside without a chance of ever obtaining asylum. Experts say Italy treats them as if they were a problem, but farm owners are perfectly happy to exploit them as cheap labor.

Suleman says the Italian system is totally unfair. But Italian people, for the most part, have been supportive.

“Everything I lived through was bad, but also good, because I really understood the meaning of humanity: Always try to help the other, and give support to someone who doesn’t have your same opportunities,” he says.

Like the woman who sponsored their first batch of milk, or the farmer who offers his professional dairy lab for free — not to mention the passionate yogurt customers — Suleman says it’s all about Barikama — resilience.