The Carolinas’ ‘thousand-year’ flood follows a big rainfall trend across the US

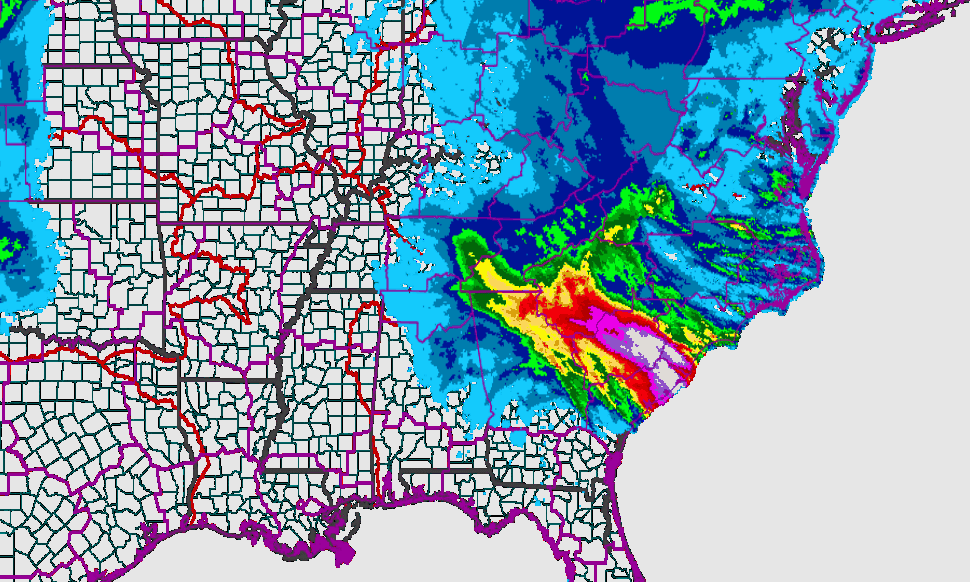

A US National Weather Service map shows precipitation levels across the southeastern US on October 4, 2015. White splotches in South Carolina indicate areas with more than 10 inches of rain.

Twenty seven inches of rain over five days. More than 15 inches in just 10 hours.

Those are just a couple of the unfathomable amounts of rain that fell in parts of South and North Carolina last weekend in the storm that killed at least 17 people and caused in the neighborhood of $1 billion in damage.

Meteorologists called it a “thousand-year event” — meaning a deluge that’s likely to happen only once in 1,000 years, but they may have to change their odds as the planet warms up. Already this year there have been two such supposedly rare rain events, and many other rainfall records set, in the US.

“Oklahoma and Texas had incomprehensible amounts of rain in May,” says Bob Henson, a blogger for the Weather Underground who worked more than 20 years at the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research in Boulder Colorado. “The amount of rain in Texas was what you would expect maybe once every two or 3000 years.”

And don’t forget the record amounts of snow that fell on New England last winter.

And what’s going on isn’t just the clustering you often find among random events.

When it rains these days, Henson says, it often rains harder.

“That's been shown through a great amount of research over the last 20 years… It's not happening in every single location, but it's happening in enough places that you could legitimately call it a global trend. The US is in line with that trend, most parts of the US are seeing this happen.”

And Henson says there’s a simple connection to climate change. The earth’s atmosphere is warming up, and when it gets warmer, he says, the oceans evaporate more moisture into the air. “So there's literally more fuel available to make it rain harder when you have a setup that’s creating rain in the first place.”

In other words, warmer temperatures may not be causing such storms, but they are helping feed more water into storm systems.

The particulars of the storm that battered North and South Carolina were a classic example of random weather events combined with the effects of the upward temperature trend.

“We had a upper-level low pressure center (that) sat over the southeast for several days,” Henson says. “That brought in a lot of forcing to pull the air upward and make it rain.” And the rainfall was in turn fed by an unusually wet atmosphere in the region.

“You had a ton of moisture available along the East Coast and moisture being funneled in from hurricane Joaquin into the Carolinas.”

The growing number of deluges bring lots of problems with them, but Henson, who wrote his master’s thesis on flash flood warnings, says one of the biggest may just be getting people to take the threat seriously.

He says the heavy rains in the Carolinas were pretty well forecast, and local officials were fairly well prepared, but regular folks still ventured out into the storms when they’d been warned not to.

“People simply don't take moving water seriously a lot of the time,” Henson says.” How many cases do you see of people driving into floodwaters and then once there, of course the vehicle gets carried off? So it's a perpetual challenge to make people realize that water in motion can be just as dangerous as, say, high winds.”