Coca is known as the main ingredient in cocaine. But for Bolivia, it’s more than that.

A chalkboard lists the day's prices for coca — according to the quality of the leaves — in the Villa Fátima legal coca market in La Paz.

When coca farmer and union leader Evo Morales was elected president in 2006, one of his first priorities was to claim coca’s rightful place in Bolivian culture. The coca leaf is not cocaine, he insisted. It represents the culture of many indigenous people in the region.

Coca, widely known as the main ingredient in cocaine, has been grown in the Andes for centuries. In Bolivia, an estimated third of the population consumes the leaf in natural form as if it were coffee, or tea.

But the sturdy leaf has also been at the heart of US-led eradication efforts in Latin America. Since the 1980s, showdowns with the military had led to killings and political instability, without managing to decrease overall cocaine production and consumption.

Not surprisingly, Morales’ pro-coca campaign did not please US officials from the moment he came into office.

“The US and Bolivia both signed a number of UN conventions, which state very clearly that both cocaine and coca leaf are controlled substances — that is to say, they’re illegal,” said Joseph Manso, former director of the Narcotics Affairs Section in the US Embassy in La Paz, back in 2008. “The United States stands by those conventions, and expects Bolivia to also comply with its international obligations.”

In a bold move, Morales responded to these kinds of threats by throwing the US Drug Enforcement Agency out of the country. Around that time, the government publicized its “Coca Si, Cocaina No” campaign, which promised to support the legal use and sale of coca while going after drug makers and traffickers.

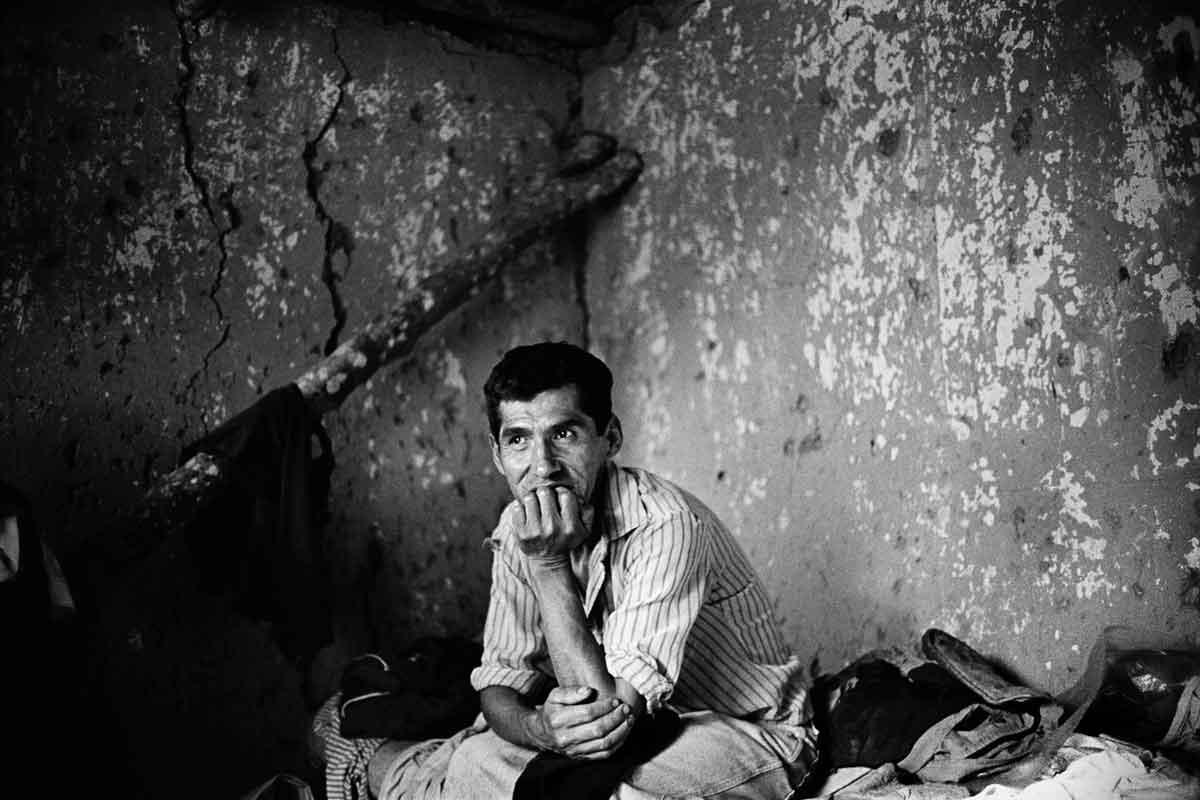

Coca farmers like Carlos Pérez were thrilled.

“They were thrown out of town,” Pérez said, referring to the ousting of the DEA agents. “People organized through the local community radio and kicked them out of coca producing villages, one by one. That’s why people around here are mistrustful; they don’t want to give up coca, which is the main source of income here in Los Yungas.”

Reaching down to touch one of his plants, Pérez boasted that his coca from the region of Los Yungas is — hands down — the best in the country. “The coca here is really tasty; the leaves are so beautiful.”

“Coca Si, Cocaina No” bet that legalizing coca, while encouraging farmers to help keep their coca out of the cocaine market, would cut down on illicit drugs. And the program seems to have paid off.

“It’s implemented in a way that rejects the basic premise of a militarized War on Drugs,” said Kathryn Ledebur, director of the Andean Information Network, and co-author of the “Habeas Coca” report.

“That old premise saw supply side control as viable; saw farmers are the enemy and active members of the drug trade,” exlains Ledebur. “It really shifts it back to the priorities of farming families and the reasons they grow coca: subsistence.”

The new report has found that Bolivia slashed its illicit coca production by 34 percent over the past four years. In fact, coca production in the country is now the lowest it has been since 2003, when the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime started using satellite imaging to monitor crops.

Violent confrontations between police and farmers have all but disappeared, and almost 25,000 acres of coca have been voluntarily removed.

US authorities have yet to respond to these specific findings. But this month, the State Department chided Bolivia’s government, saying “it has neither maintained adequate controls over licit coca markets to prevent diversion to illegal narcotics production, nor has it closed illegal coca markets.”

Currently, one percent of cocaine consumed in the US is believed to originate in Bolivia. Colombia produces more than half of the world’s cocaine, followed by Peru.

Roxana Argandoña Vargas, a farmer and mother of four children from Bolivia’s other coca growing region, the Chapare, isn’t interested in what the US says. She’s thrown her full support behind President Evo Morales.

“Our wish now is that he should be re-elected for another five years, until 2025 — that’s what we hope for,” said Argandoña Vargas. “We think that if the president doesn’t win, we’ll end up with a war against coca farmers, again.”

But Vargas recognizes she has no way of knowing whether any of her coca is diverted to the cocaine market. “All I know is that we can now make a living growing coca, like our great-grandparents did,” she said. “We’re just farmers; we’re not cocaine traffickers.”

Update: A previous version of this story incorrectly listed Kathryn Ledebur's co-authored report, “Building on Progress." It is titled "Habeas Coca."