Cities like Boston are redesigning their streets for the people who use them

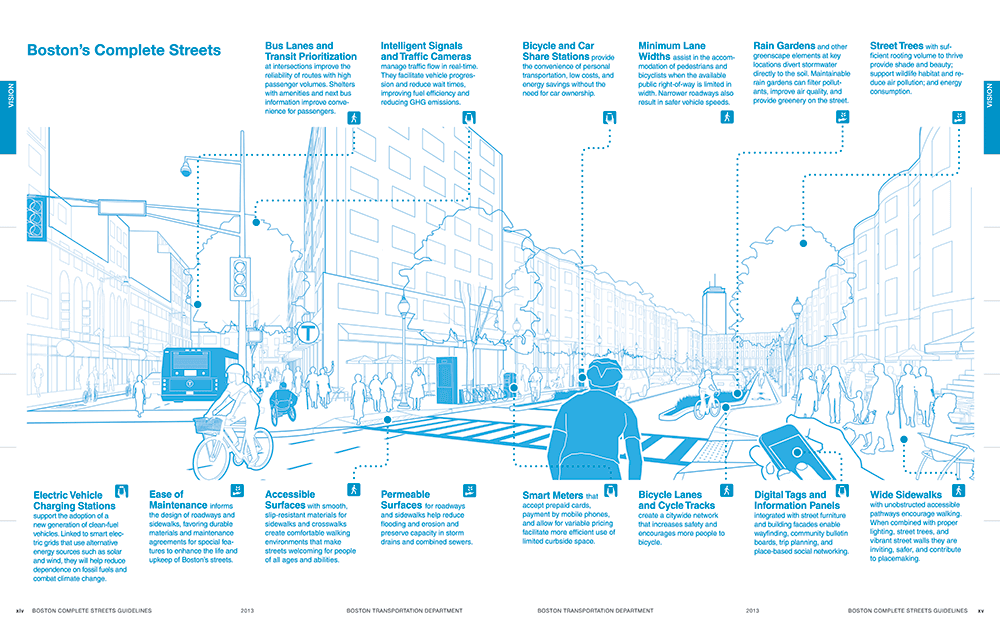

A “menu” of different options that could be included in “Complete Street” redesigns in the city of Boston.

In big cities and rural towns, many communities are beginning to use a concept called “Complete Streets” to make neighborhood and commercial streets friendlier for people. The policies behind these changes are new, but the problems and complaints they are addressing are often as old as the roads they aim to fix.

“Complete streets” look different in different places, but the idea is simple: Make transportation systems about people, so there is equal access for all forms of travel.

In Boston’s Allston neighborhood, the Complete Streets movement centers on a problematic busy street called Cambridge Street. Since Cambridge Street was last redesigned 50 years ago, it has been high on the list of residents’ complaints.

“Cambridge Street is a crucial link in our neighborhood, and it’s also an incredibly unsafe, dangerous street,” says Harry Mattison, a 31-year-old software developer who is a longtime advocate for pedestrian and cyclist rights in the area. Pattison is one of a small group of locals who are demanding a safer Cambridge Street. Mattison has three kids and laments not feeling safe on a street that cuts through the heart of his own neighborhood.

“I want to be able to walk with my kids, to bike with my kids, to drive safely in the neighborhood where I live, and we just can’t do that today because this street is so poorly designed and so unsafe,” he says.

The city is working on a short-term fix to make Cambridge Street safer. But in the long term, Boston’s transportation department has bigger plans. It’s going to bring the street into the modern day and transform it using the principles of Complete Streets.

Vineet Gupta, the head of policy and planning for the transportation department, says in Boston, every street redesign, including the one for Cambridge Street, will include a handful of features from a menu of possibilities.

“Any street that’s going through a redesign process will have some elements of Complete Streets in it, based on its size, based on what the community wants and based on where it’s located,” Gupta says.

In some places this is as simple as narrowing the road by adding a bike lane. Projects with more space and better funding, like Cambridge Street, might also allow for new bike sharing stations, more trees along the street or smart parking meters that direct drivers to open spaces. The final street design will be tailored toward the wants and needs of the people who use it, Gupta says.

“There may be some streets, for example, where wide sidewalks are really important because restaurant owners want to see cafes opening onto those wide sidewalks. That might mean that the bicycle facility is not a cycle track, but just a bicycle lane.“

On streets that see more bus traffic, on the other hand, exclusive bus lanes might take priority over a bike lane, he explains.

Designing streets according to how people use them makes sense, but it marks a major change in the way we think about how we get around. When Cambridge Street was first built, highway engineers had one aim in mind.

“After World War II, the United States and many other countries embarked on a massive infrastructure investment [designed to] move goods across the country,” says Stefanie Seskin, the deputy director of the National Complete Streets Coalition. “That created a lot of really good and important changes to the way we built our roads, in terms of safety when you’re traveling at high speeds.”

But, Seskin says, while wide lanes make highways and other high-speed roads safer for traffic using them, they were never meant for cities and town centers. Vineet Gupta agrees that the post-war engineering mentality explains why Cambridge Street is so bad for pedestrians today.

“In those days, all they cared about was moving traffic and making traffic flow more efficiently, and really not focusing on what cities really are, and what makes them livable,” Gupta says.

That’s where the people-oriented concept of complete streets is different — and the idea has been gaining traction around the country.

The National Complete Streets Coalition says that the number of places with complete street policies leaped from 86 in 2008 to 610 last year. And now there’s a federal Complete Streets policy in the works. The Safe Streets Act is under consideration in both the House and the Senate. The act would require all federally funded transportation projects to comply with Complete Street principles that Seskin calls pretty close to ideal.

Stephanie Seskin says the name Complete Streets has itself helped these ideas catch on.

“The Complete Streets movement really got a lot of traction because it put a nice name on this more abstract idea that lots of people already had for what they wanted in their communities,” Seskin says. “We don’t want to have to drive everywhere. We want choices; we want it to be safe; and we want our kids to have the opportunity to ride their bikes in our neighborhood without the parents worrying about it.”

That just what Mattison and other Allston residents are asking of Boston — a street where they can bike and walk safely with their kids. And, though it may take until the end of the decade to make it happen, the City of Boston is giving them one.

This article is based on a story that aired on PRI's Living on Earth with Steve Curwood.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?