In Massachusetts, old military explosives washing ashore is just another day at the beach

Ordnance that recently washed up on a beach in Cape Cod, Massachusetts.

Speculation ran wild in the days following a Rhode Island beach explosion last month. One of the early theories posed that it might have been an old military munition buried in the sand.

That explosion was caused by the build-up of gases from an underbeach Coast Guard communications cable, but the theory of an unexploded munition isn't exactly far fetched. It’s fairly common, actually.

This time last year, a small crowd gathered at Marconi Beach in Wellfleet, Massachusetts, to watch from a distance as the state bomb squad detonated a 14-inch projectile found buried in the sand.

The unexploded ordnance was still live, despite the fact that it was some 70 years old. Sgt. William Qualls, who heads the Massachusetts state bomb squad, says, during World War II, large-scale Naval exercises were held along the coast. A mock German village was even built on Cape Cod to prepare soldiers for urban warfare. At the time, the area was crawling with munitions. As it turns out — it still is.

oembed://https%3A//www.youtube.com/watch%3Fv%3D49FQolZWCeg

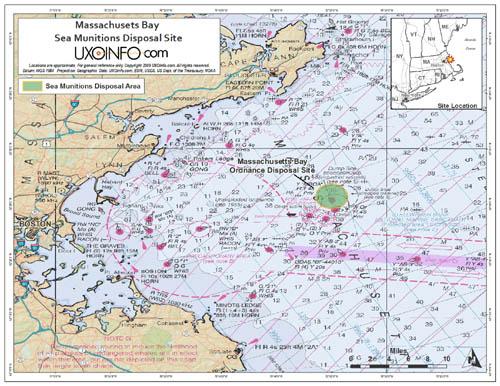

“It would be beyond me to speculate,” says Qualls, “but it’s common knowledge that there were large amount of ordnance dumped off into the water, into the deep seas.”

Perhaps the biggest source of unexploded ordnance comes from a decision, after World War II, to dump tens of thousands, maybe even hundreds of thousands, of tons of surplus artillery and munitions into the waters off the Atlantic coast.

Included in that cache were artillery shells, 37-millimeter projectiles, 75-millimeter projectiles, bombs, mark–23 torpedoes, mines, grenades and a couple of pyrophoric rounds. In addition, the US Army's Dave Foster says “chemical warfare munitions sea disposals occurred between 1919 and 1970, when it was both an authorized method of disposal and remained an accepted practice.”

In short, a whole lot of nasty stuff. And some seven decades later, Qualls says it’s still finding its way back to shore.

“If you average out our number, we respond to about 15 military calls or military item requests per month, on average,” he says.

A majority of those are actually house calls. Someone’s cleaning out their parent’s — or grandparent’s home and finds a grenade or a mortar shell in the basement. Still, beach calls happen all the time.

Ninety percent of the items that wash up on New England shores or are discovered in beach areas are from the World War II era.

The majority prove to be inert, but not all. And Qualls and his 12-person team know exactly how to deal with most of them. Still, there is the occasional surprise, usually found by fishermen– further out in the water.

“A torpedo was brought into Provincetown port,” Qualls says. “We had a depth charge brought into Gloucester. We had mustard [gas — a chemical weapon] munitions brought into New Bedford. Those are the most notable ones.”

There’s a reason for this. The more dangerous and noxious weapons were dumped further out, at greater depths. Foster says that in recent years, they’re increasingly being dredged up.

“The fishing industry is now bringing them up with their catch,” says Foster, “because the technology — the advanced technology — allows them to go further out, go deeper.”

Foster says the Army works closely with the fishing industries to put safety measures and procedures in place. But Massachusetts has a vast coastline. And that’s why Sgt. Qualls stresses that if you find something curious on the beach, whatever you do, don’t touch it.

“Treat it with the utmost respect,” says Qualls. “Treat it as live until proven otherwise by the professionals. To mark it, to make notice of the location and then to contact the local authorities immediately.”

Thankfully, injuries are exceedingly rare, still Qualls stresses that even the smallest movement can cause unexploded ordnance to do harm. After all, that’s exactly what they were designed to do.

A version of this story first appeared on WGBHNews.org.