Welsh is considered a model for language revitalization, but its fate is still uncertain

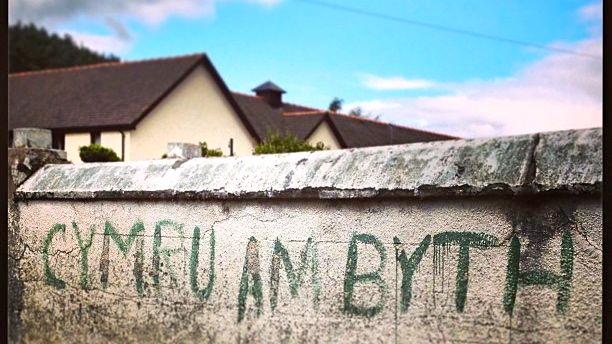

Graffiti in the Welsh town of Machynlleth. Translation: Wales forever.

Welsh is just another of those ancient languages that aren’t going to be around for much longer, right?

Maybe. Maybe not. It’s difficult to tell.

But it is a test case, a minority language with a chance of surviving. If Welsh can do it, maybe others can too.

The stakes are high, not just for the 740,000 people who speak Welsh today but for speakers of thousands of minority languages around the world.

Like its Celtic cousins Scottish Gaelic and Irish, Welsh suffers from its proximity to the English-speaking world. But Welsh has stuck around while the other Celtic languages have lost most of their speakers. In Scotland, many assert their difference from Britain by voting for independence. In Wales, they do it by speaking Welsh.

“I never heard Welsh in my family,” says Julian Ruck, a writer who grew up in Swansea in the 1960s. “I never heard Welsh at school, and I never heard the Welsh language amongst my friends.”

After finishing school, Ruck left Wales for London and didn’t return for 30 years.

“It was a culture shock when I came back,” says Ruck. “I had no idea that the promotion of the Welsh language had progressed so far. It was almost like coming back to a foreign country.”

Ruck isn’t happy about this turn of events. But he’s in a minority. Most Welsh people want the language to stick around.

Today, there are TV shows in Welsh, produced in local studios. There are schools too that use Welsh as the language of instruction. In Cardiff alone, there are 17 Welsh-language elementary schools. Thirty years ago, there was one.

“Their children are going to Welsh language schools, so the parents go to evening classes to learn Welsh,” says Ian Cox, who himself is taking classes in Cardiff.

“I lived here all my life and decided it’s about time … to learn the language,” Cox says. “Everywhere we go abroad people say, ‘Do you speak Welsh?’ and it was embarrassing that we couldn’t, so we decided to learn.”

“When I was living in Hong Kong, I didn’t learn the local language — Cantonese.” she says. “I regret it. So I have decided that wherever I live, I will learn the local language.”

Her Welsh, she says, isn’t bad.

“At the moment, I can understand local TV in Welsh,” she says. “Not that I’m that crazy about rugby, but it is nice to see things that are only in Welsh.”

The commitment of so many to the language is impressive. Of course, these are learners. To become fluent, to turn themselves into something approaching natural speakers, they’d need to take things further.

That’s what Jamie Bevan did. His first language is English, although he studied some Welsh at school. When he was in his late 20s, he and his family — mother, siblings and finally his father — decided to start talking to each other in Welsh.

“Definitely not,” Bevan says. “All of us as a family have gained so much. It’s something we regret not having done earlier.”

Bevan has expressed that zeal in other ways. He is language activist and chairman of the Welsh Language Society. He has served jail time for acts of civil disobedience, like refusing to respond to court summons written in English.

Protest has been at the heart of Welsh language activism for decades. It’s helped Welsh achieve its official status, alongside English.

What Bevan has done with his family is clearly exceptional. It’s the private, personal nature of it — the part that is missing in most Welsh learners’ experience of the language. Children are learning Welsh in schools, but what about at home? How can non-native speakers make that leap to growing up in Welsh, playing games in Welsh, falling in love in Welsh?

It is something that Welsh Language Commissioner Meri Huws thinks about a lot.

“We now have young people who are first generation Welsh within their families,” says Huws. “Within the home environment they have no one else to communicate with in that language.”

Many of these new first generation Welsh speakers are in their teens now. Huws says the challenge is to ensure that they have the opportunity to communicate in Welsh outside the structured environment of school.

Huws is the first Welsh language commissioner; the role was established in 2011. Her office issues advice and directives on the use of Welsh, although the extent of her authority is still unclear.

For language activists, the commissioner’s oversight should help ensure the future of Welsh. For Julian Ruck — the writer who returned to Wales after an absence of 30 years — it’s just another wasteful layer of bureaucracy.

“I just do not believe that it merits having tax payers’ hard-earned money being spent on it, particularly as it is — or seems to be — dying,” says Ruck. “Throwing all this money at it has not worked.”

Now that may sound like an odd conclusion given all the enthusiasm for the language. But Ruck has a point. Welsh is imperilled — not in the cities where people are taking it up but in the places where it is spoken naturally: rural, often poor parts of north and west Wales.

“There’s been a great change in the demography of the area over the past 30 to 40 years,” says Peredur Lynch who heads the School of Welsh at the Bangor University. “You’d have to go back to medieval times to see such big change in the population in this part of the world.”

Retirees from across the border in England have moved to this area in huge numbers, and they are setting a new linguistic path.

Lynch grew up in a village that was mainly Welsh-speaking. He didn’t start speaking English until he was 8 or 9. Today, the village is no longer majority Welsh.

As for his own family, Lynch’s children speak Welsh at home and at school, “But of course they pick up English, it’s all around them. They watch The Simpsons.”

Under such circumstances, it doesn’t take much, linguists say, for a minority language community to flip to the majority language. Once a community drops below 70 percent minority language speakers, it’s in trouble. The part of Wales that Lynch comes from is down to 69 percent Welsh speakers.

The latest national census also reflects that. It finds fewer Welsh speakers overall. Some policymakers are now calling for protective measures — even so far as restricting new housing projects if they dilute the concentration of Welsh speakers.

“A friend of mine asked me: ‘Why don’t you try rapping in Welsh?’” he says. “I found out it was more natural to rap in my native language.”

Now that he’s switched languages, Dybl-L finds his raps about more personal stuff

“Living with a single parent, breaking up with girlfriends and stuff like that,” he says of his subject matter. “I feel I can put more feeling into my words when I rap in Welsh.”

It’s impossible to know yet what’ll happen to Welsh. Clearly many people feel more comfortable using it. Even some people who don’t speak it well — or at all — view it with intense pride. And yet, the threats are real, and growing. What would happen to the language if its linguistic heartlands — its lungs, as one activist puts it — collapsed? Would the revival of Welsh elsewhere withstand such a blow?

Its fate will be closely observed, especially in those few pockets of linguistic diversity in the English-speaking world.

Whatever happens, Welsh has become a test case for language survival — and possibly, revival.