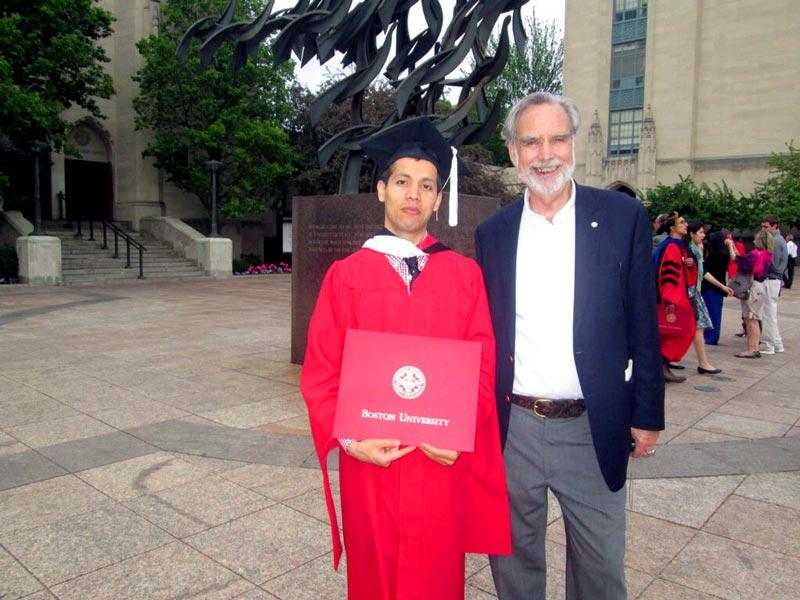

Qais Akbar Omar and longtime friend Stephen Landrigan.

Afghanistan’s millennials are the best-educated generation in their country’s history and represent its future. For the past three years, one of them — Qais Akbar Omar — has been studying in the Boston area. He is a writer, but his success has come at a price.

Omar lives on the first floor of an ordinary looking house in Quincy, but stepping inside his apartment, you are immediately transported to a different place. Spread on the floors are beautiful, hand-woven rugs from his family’s carpet business in Kabul. One is made up of four rectangular prayer rugs all woven together and rendered in reds, oranges and blacks. In the kitchen, there is a woolen rug, traditionally used by nomads, that is edged with goat hair to keep out scorpions and snakes — not exactly common in Quincy.

“We also use it in Kabul,” he says. “Most of the houses in Afghanistan are made of mud brick or concrete. Our house is concrete, so we put this under the carpet and then that will keep the cold away.”

But today Omar has more on his mind than carpets. He is getting ready for his commencement. He slips on a scarlet red graduation gown.

“In Afghanistan, men normally don’t wear red — it’s considered a woman’s color,” he says. “Today my gown is red.”

Omar is graduating from Boston University with an MFA in creative writing. He moved to Boston three years ago to finish an education that was cut short by Afghanistan’s long civil war. Omar wrote about those painful years in his memoir, "A Fort of Nine Towers," which has been translated into more than 20 languages.

"Then one thing led to the next, and now I can’t go back,” he says. “The book got so much publicity.”

Omar’s growing success as a writer, and his outspoken criticism of those in power, has created problems for him and his family back in Kabul.

"I wrote an op-ed for The New York Times about ghost money that the CIA was giving to President [Hamid] Karzai at the time,” he explains. “As soon as that one came out, we got a lot of visitors coming to our shop, trying to take me to lunch. And, of course, you go to that lunch and you never come back."

Omar’s father was forced to close the carpet business, which had been in the family for four generations. Last year he called Omar with sad news. Omar’s mother had passed away.

"I told him, I’ll buy my ticket right now and I’ll be there for the funeral," he recalls. "And my father stopped crying and said, 'No, you can’t come.' He was afraid that if I went there, a suicide bomber might have come into the funeral and blew himself up."

Omar says he still cannot return home and he hopes to stay in Boston.

Helping Omar get ready is his longtime friend, Stephen Landrigan. Landrigan and Omar’s love of theater brought them together in Kabul in 2005, when they put on a groundbreaking production of Shakespeare’s: "Love’s Labour’s Lost."

It featured Afghan actors, male and female, performing together in their native tongue, Dari. With the deteriorating security situation in Afghanistan, many of the actors have since fled the country.

At Boston University, Omar’s commencement is a success and his friend, Landrigan, says it is a day he deserves.

“This guy is a power house,” he says. “Many people say I’m a writer, but this guy gets up in the morning and actually writes.”

Omar has written two novels, a collection of short stories, two novellas and more. Landrigan says he has great expectations for Omar’s future.

“He is going to become recognized as much of the writer of Afghanistan that Naguib Mahfouz is of Egypt,” he says. “All of the stories that he will be exploring between now and then will create a body of literature so that the outside world will understand Afghanistan in a way that we really didn’t after we went in there after 9/11.”

For now, the only way Omar can write about his country is in exile and it is a reality he is conflicted about.

"I really want to be back to help my country," he says. "Afghanistan is run by the young generation, my generation, even though my generation went through hell. I want to do more, but not if it costs my life — then I won’t be able to do anything, I’ll be in the ground."

This story was crossposted at WGBH News as part of a collaboration with The GroundTruth Project. Read more at Foreverstan.