A community bio-tech lab offers a crash course in designing life — open to the public

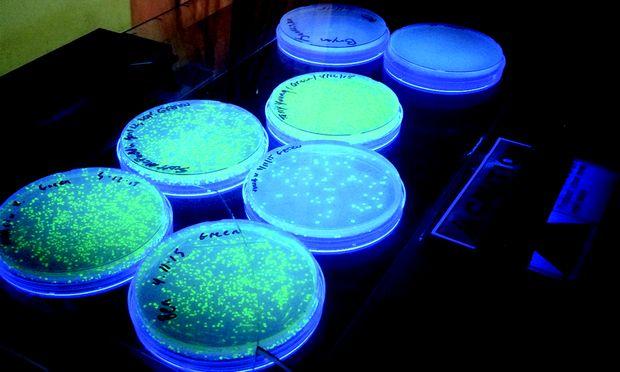

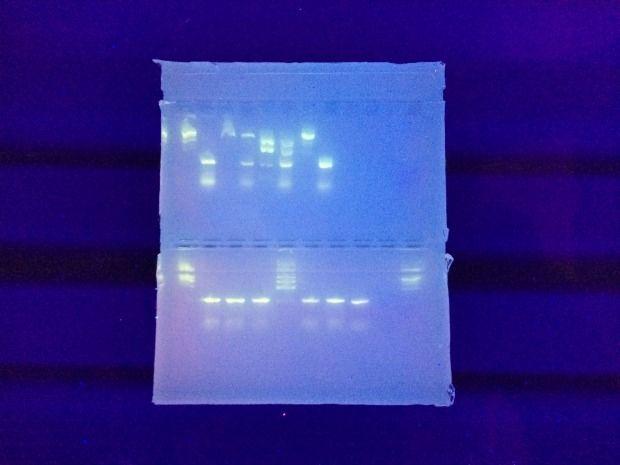

Reporter Julia Wetherell took Genspace's three-day course in synthetic biology. On day one, she transformed E-coli bacteria with jellyfish DNA to make the E-coli bio-fluorescent.

Dr. Ellen Jorgensen believes everyone should have access to biotechnology.

“Scientists in general are awful at communicating their work to the general public,” says Jorgensen, the director of Genspace. “The consumer is already using genetically modified and genetically engineered products in their daily life. So, wouldn't it be nice if the end user were also someone who could have a say about what this technology was used for?“

Genspace, which opened in downtown Brooklyn in 2009, is the world's first community bio-lab. It offers a three-class crash course in synthetic biology to anyone who is interested. It also has a working lab space where the general public is invited to come in and learn how to do genetic science — hands on.

For $100 a month, Genspace members have access to the standardized gene sets that are the building blocks of synthetic biology. If that sounds daunting, consider this: Non-scientists make up a big part of Genspace membership. “To my surprise, at one point we found that most of the people doing work in Genspace were artists,” Jorgensen says.

One of these is Sarah Berman, a scientific illustrator who has been using Genspace to create a type of paint made from fluorescent bacteria. For the past several months, Berman has been cultivating petri dishes full of fluorescent bacteria. They are transformed with various synthetic, altered plasmids to produce different colors. She’ll layer them onto her illustrations of endocrine organs, creating a mixed media installation that comments on organic communication systems in our bodies and in bacterial colonies.

“I feel very lucky that such a space exists, where I can just kind of play with the idea of these things and learn a lot about it, without really much judgement,” Berman says. “Here I am, a scientific Illustrator, coming into a biology laboratory and working with various strains of bacteria. I think that's pretty cool.”

Opening up the gates of bio engineering to unusual suspects could drive big discoveries of the future. As Jorgensen points out, Gregor Mendel, the father of modern genetic science, was a DIY bio, an amateur biologist.

As genetic engineering continues to shape our lives, Genspace and organizations like it are offering people the chance to take things into their own hands.

“I would like to see everybody have a working knowledge of things like genetic engineering, the same way we have working knowledge of electricity,” Jorgensen says. “We treat electricity with respect, but we're not afraid of it. I think we need to get to that place with some of the new DNA science.”

This article is based on a story reported by Julia Wetherell for PRI's Studio 360 with Kurt Andersen